J Breast Cancer.

2019 Jun;22(2):196-209. 10.4048/jbc.2019.22.e23.

Inhibition of Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase Enhances the Therapeutic Efficacy of Immunogenic Chemotherapeutics in Breast Cancer

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Clinical Medicine, Clinical Medical College of Shandong University, Jinan, China.

- 2Department of General Surgery, the First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology of China, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China.

- 3Department of Hepatic Surgery, the First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology of China, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China. wdjia2018@sina.com

- KMID: 2450115

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4048/jbc.2019.22.e23

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Breast cancer has become a major public health threat in the current society. Anthracycline doxorubicin (DOX) is a widely used drug in breast cancer chemotherapy. We aimed to investigate the immunogenic death of breast tumor cells caused by DOX, and detect the effects of combination of DOX and a small molecule inhibitor in tumor engrafted mouse model.

METHODS

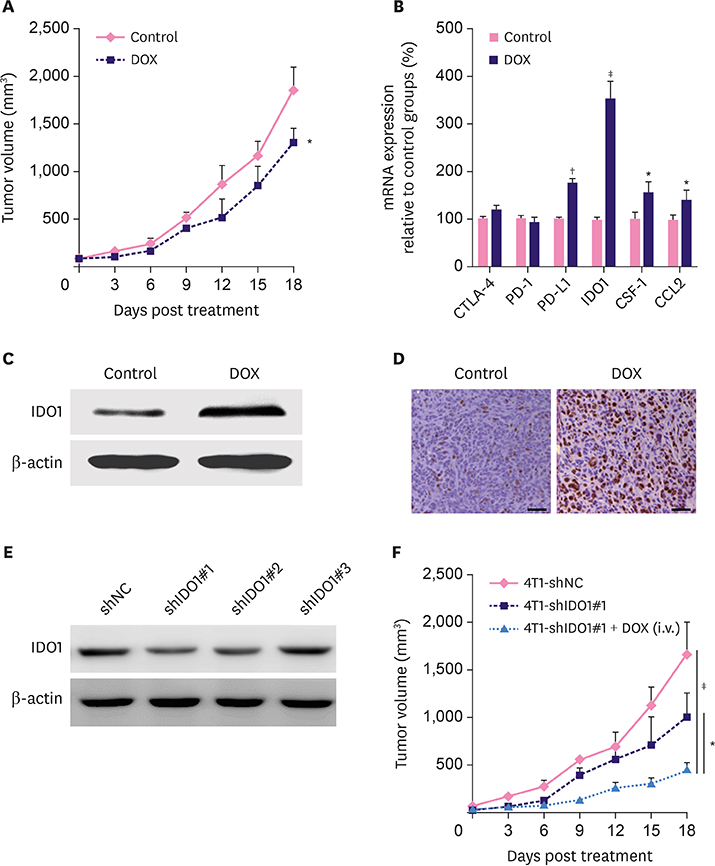

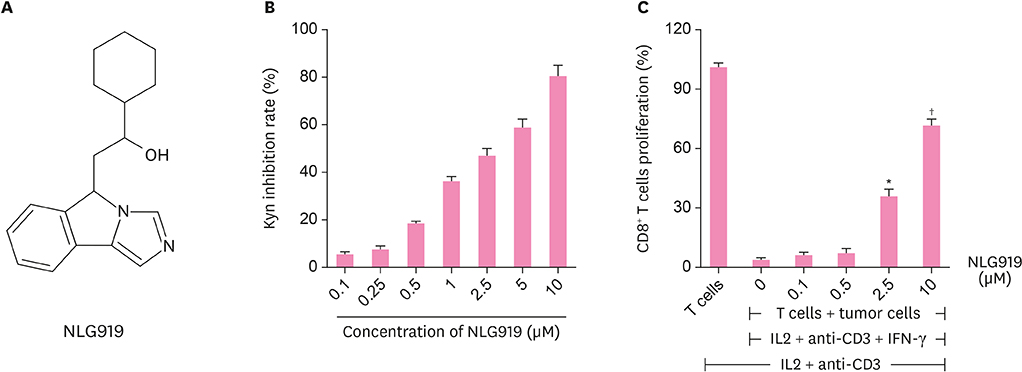

We used 4T1 breast cancer cells to examine the anthracycline DOX-mediated immunogenic death of breast tumor cells by assessing the calreticulin exposure and adenosine triphosphate and high mobility group box 1 release. Using 4T1 tumor cell-engrafted mouse model, we also detected the expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) in tumor tissues after DOX treatment and further explored whether the specific small molecule IDO1 inhibitor NLG919 combined with DOX, can exhibit better therapeutic effects on breast cancer.

RESULTS

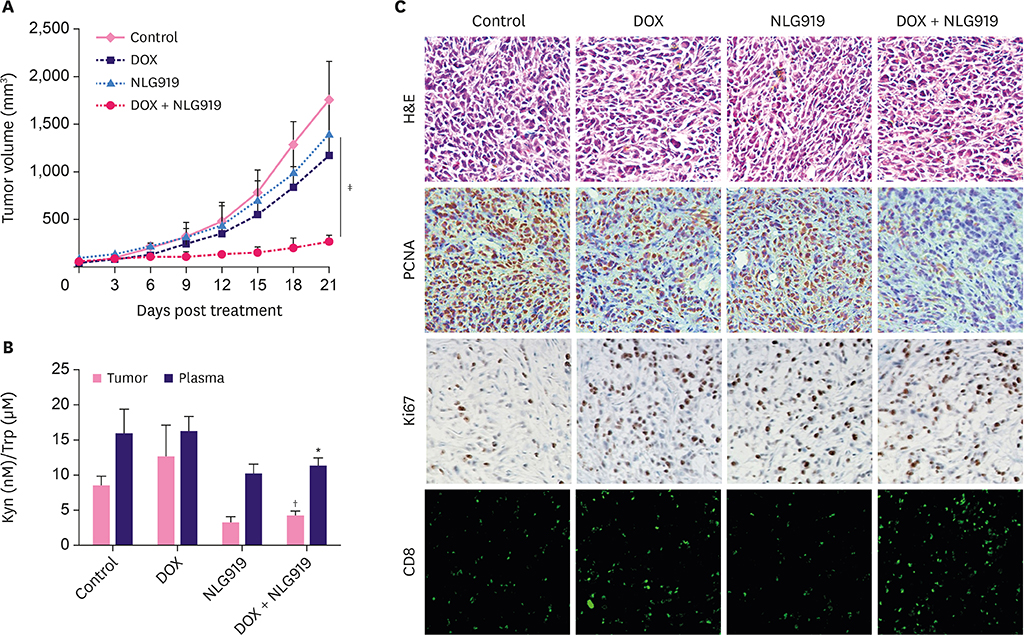

DOX induced immunogenic cell death of murine breast cancer cells 4T1 as well as the upregulation of IDO1. We also found that treatment with NLG919 enhanced kynurenine inhibition in a dose-dependent manner. IDO1 inhibition reversed CD8+ T cell suppression mediated by IDO-expressing 4T1 murine breast cancer cells. Compared to the single agent or control, combination of DOX and NLG919 significantly inhibited the tumor growth, indicating that the 2 drugs exhibit synergistic effect. The combination therapy also increased the expression of transforming growth factor-β, while lowering the expressions of interleukin-12p70 and interferon-γ.

CONCLUSION

Compared to single agent therapy, combination of NLG919 with DOX demonstrated better therapeutic effects in 4T1 murine breast tumor model. IDO inhibition by NLG919 enhanced the therapeutic efficacy of DOX in breast cancer, achieving synergistic effect.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Hutchinson L. Breast cancer: challenges, controversies, breakthroughs. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010; 7:669–670.2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017; 67:7–30.

Article3. Anampa J, Makower D, Sparano JA. Progress in adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: an overview. BMC Med. 2015; 13:195.

Article4. Sledge GW, Mamounas EP, Hortobagyi GN, Burstein HJ, Goodwin PJ, Wolff AC. Past, present, and future challenges in breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2014; 32:1979–1986.

Article5. Garg AD, More S, Rufo N, Mece O, Sassano ML, Agostinis P, et al. Trial watch: Immunogenic cell death induction by anticancer chemotherapeutics. OncoImmunology. 2017; 6:e1386829.

Article6. Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Zitvogel L. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013; 31:51–72.

Article7. Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan V, Fearon DF, Merad M, et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med. 2018; 24:541–550.

Article8. Lu J, Liu X, Liao YP, Salazar F, Sun B, Jiang W, et al. Nano-enabled pancreas cancer immunotherapy using immunogenic cell death and reversing immunosuppression. Nat Commun. 2017; 8:1811.

Article9. Moon YW, Hajjar J, Hwu P, Naing A. Targeting the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase pathway in cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2015; 3:51.

Article10. Chen X, Parelkar SS, Henchey E, Schneider S, Emrick T. PolyMPC-doxorubicin prodrugs. Bioconjug Chem. 2012; 23:1753–1763.

Article11. Yue EW, Douty B, Wayland B, Bower M, Liu X, Leffet L, et al. Discovery of potent competitive inhibitors of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase with in vivo pharmacodynamic activity and efficacy in a mouse melanoma model. J Med Chem. 2009; 52:7364–7367.

Article12. Munn DH, Shafizadeh E, Attwood JT, Bondarev I, Pashine A, Mellor AL. Inhibition of T cell proliferation by macrophage tryptophan catabolism. J Exp Med. 1999; 189:1363–1372.

Article13. Tacar O, Sriamornsak P, Dass CR. Doxorubicin: an update on anticancer molecular action, toxicity and novel drug delivery systems. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2013; 65:157–170.

Article14. Müller I, Jenner A, Bruchelt G, Niethammer D, Halliwell B. Effect of concentration on the cytotoxic mechanism of doxorubicin--apoptosis and oxidative DNA damage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997; 230:254–257.

Article15. Dickey JS, Rao VA. Current and proposed biomarkers of anthracycline cardiotoxicity in cancer: emerging opportunities in oxidative damage and autophagy. Curr Mol Med. 2012; 12:763–771.

Article16. Mizutani H, Tada-Oikawa S, Hiraku Y, Kojima M, Kawanishi S. Mechanism of apoptosis induced by doxorubicin through the generation of hydrogen peroxide. Life Sci. 2005; 76:1439–1453.

Article17. Rosch JG, Brown AL, DuRoss AN, DuRoss EL, Sahay G, Sun C. Nanoalginates via inverse-micelle synthesis: doxorubicin-encapsulation and breast cancer cytotoxicity. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2018; 13:350.

Article18. Munn DH, Mellor AL. IDO in the tumor microenvironment: inflammation, counter-regulation, and tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2016; 37:193–207.

Article19. Löb S, Königsrainer A, Rammensee HG, Opelz G, Terness P. Inhibitors of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase for cancer therapy: can we see the wood for the trees? Nat Rev Cancer. 2009; 9:445–452.

Article20. Prendergast GC, Malachowski WP, DuHadaway JB, Muller AJ. Discovery of IDO1 inhibitors: from bench to bedside. Cancer Res. 2017; 77:6795–6811.

Article21. Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015; 348:56–61.

Article22. Selvan SR, Dowling JP, Kelly WK, Lin J. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO): biology and target in cancer immunotherapies. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2016; 16:755–764.

Article23. Qin Y, Ekmekcioglu S, Forget MA, Szekvolgyi L, Hwu P, Grimm EA, et al. Cervical cancer neoantigen landscape and immune activity is associated with human papillomavirus master regulators. Front Immunol. 2017; 8:689.

Article24. Laimer K, Troester B, Kloss F, Schafer G, Obrist P, Perathoner A, et al. Expression and prognostic impact of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2011; 47:352–357.

Article25. Zhai L, Ladomersky E, Lauing KL, Wu M, Genet M, Gritsina G, et al. Infiltrating T Cells increase IDO1 expression in glioblastoma and contribute to decreased patient survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2017; 23:6650–6660.

Article26. Uyttenhove C, Pilotte L, Théate I, Stroobant V, Colau D, Parmentier N, et al. Evidence for a tumoral immune resistance mechanism based on tryptophan degradation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Nat Med. 2003; 9:1269–1274.

Article27. Muller AJ, DuHadaway JB, Donover PS, Sutanto-Ward E, Prendergast GC. Inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, an immunoregulatory target of the cancer suppression gene Bin1, potentiates cancer chemotherapy. Nat Med. 2005; 11:312–319.

Article28. Cook AM, Lesterhuis WJ, Nowak AK, Lake RA. Chemotherapy and immunotherapy: mapping the road ahead. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016; 39:23–29.

Article29. Meng X, Du G, Ye L, Sun S, Liu Q, Wang H, et al. Combinatorial antitumor effects of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibitor NLG919 and paclitaxel in a murine B16-F10 melanoma model. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2017; 30:215–226.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The role of placental indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in human pregnancy

- Induction of Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by Pre-treatment with Poly(I:C) May Enhance the Efficacy of MSC Treatment in DSS-induced Colitis

- Expression of Local Immunosuppressive Factor, Indoleamine 2,3-dixygenase, in Human Coreal Cells

- The tryptophan utilization concept in pregnancy

- Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitors Attenuate Neuroinflammation Following Focal Cerebral Ischemia in Mice