Korean Circ J.

2019 May;49(5):384-399. 10.4070/kcj.2019.0114.

The Past, Present and Future of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

- Affiliations

-

- 1The Christ Hospital Heart and Vascular Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA. eugene.chung@thechristhospital.com

- 2The Lindner Center for Research and Education, Cincinnati, OH, USA.

- 3Division of Cardiology, Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, Hwaseong, Korea. jong.chan.youn@gmail.com

- KMID: 2444959

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2019.0114

Abstract

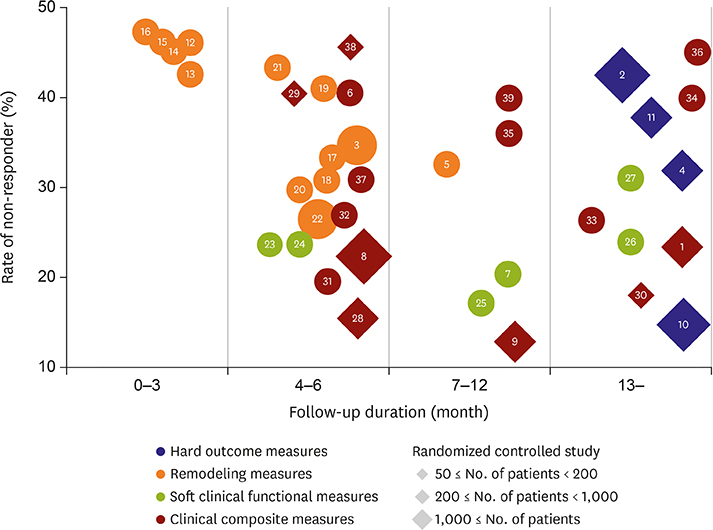

- Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) has revolutionized the care of the patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and electrical dyssynchrony. The current guidelines for patient selection include measurement of left ventricular systolic function, QRS duration and morphology, and functional classification. Despite consistent and increasing evidence supporting CRT use in appropriate patients, CRT has been underutilized. Notwithstanding the heterogeneous definitions of non-response, more than one-third of patients demonstrate a lack of echocardiographic reverse remodeling or poor clinical outcome following CRT. Since the causes of this non-response are multifactorial, it will require multidisciplinary efforts to overcome including optimal patient selection, procedural strategies, as well as optimizing post-implant care in patients undergoing CRT. The innovations of novel pacing approaches combined with advanced imaging technologies may eventually offer a personalized CRT system uniquely tailored to each patient's dyssynchrony signature.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Korean Society of Heart Failure Guidelines for the Management of Heart Failure: Treatment

Jong-Chan Youn, Darae Kim, Jae Yeong Cho, Dong-Hyuk Cho, Sang Min Park, Mi-Hyang Jung, Junho Hyun, Hyun-Jai Cho, Seong-Mi Park, Jin-Oh Choi, Wook-Jin Chung, Byung-Su Yoo, Seok-Min Kang,

Korean Circ J. 2023;53(4):217-238. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2023.0047.

Reference

-

1. Choi HM, Park MS, Youn JC. Update on heart failure management and future directions. Korean J Intern Med. 2019; 34:11–43.

Article2. Youn JC, Han S, Ryu KH. Temporal trends of hospitalized patients with heart failure in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:16–24.

Article3. Kim MS, Lee JH, Kim EJ, et al. Korean guidelines for diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:555–643.4. Lee JH, Kim MS, Kim EJ, et al. KSHF guidelines for the management of acute heart failure: part I. definition, epidemiology and diagnosis of acute heart failure. Korean Circ J. 2019; 49:1–21.

Article5. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:2129–2200.6. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62:e147–e239.7. Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:e6–e75.8. Normand C, Linde C, Singh J, Dickstein K. Indications for cardiac resynchronization therapy: a comparison of the major international guidelines. JACC Heart Fail. 2018; 6:308–316.9. Chatterjee NA, Heist EK. Cardiac resynchronization therapy-emerging therapeutic approaches. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2018; 20:20.

Article10. Daubert C, Behar N, Martins RP, Mabo P, Leclercq C. Avoiding non-responders to cardiac resynchronization therapy: a practical guide. Eur Heart J. 2017; 38:1463–1472.

Article11. Leyva F, Nisam S, Auricchio A. 20 years of cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 64:1047–1058.

Article12. Chatterjee NA, Singh JP. Cardiac resynchronization therapy: past, present, and future. Heart Fail Clin. 2015; 11:287–303.13. Abraham WT, Fisher WG, Smith AL, et al. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:1845–1853.

Article14. Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, et al. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:1539–1549.

Article15. Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1329–1338.

Article16. Tang AS, Wells GA, Talajic M, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for mild-to-moderate heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:2385–2395.

Article17. Wilkoff BL, Cook JR, Epstein AE, et al. Dual-chamber pacing or ventricular backup pacing in patients with an implantable defibrillator: the Dual Chamber and VVI Implantable Defibrillator (DAVID) trial. JAMA. 2002; 288:3115–3123.18. Hochleitner M, Hörtnagl H, Ng CK, Hörtnagl H, Gschnitzer F, Zechmann W. Usefulness of physiologic dual-chamber pacing in drug-resistant idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1990; 66:198–202.

Article19. Hochleitner M, Hörtnagl H, Hörtnagl H, Fridrich L, Gschnitzer F. Long-term efficacy of physiologic dual-chamber pacing in the treatment of end-stage idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1992; 70:1320–1325.

Article20. Auricchio A, Sommariva L, Salo RW, Scafuri A, Chiariello L. Improvement of cardiac function in patients with severe congestive heart failure and coronary artery disease by dual chamber pacing with shortened AV delay. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1993; 16:2034–2043.

Article21. Gold MR, Feliciano Z, Gottlieb SS, Fisher ML. Dual-chamber pacing with a short atrioventricular delay in congestive heart failure: a randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995; 26:967–973.

Article22. Aaronson KD, Schwartz JS, Chen TM, Wong KL, Goin JE, Mancini DM. Development and prospective validation of a clinical index to predict survival in ambulatory patients referred for cardiac transplant evaluation. Circulation. 1997; 95:2660–2667.

Article23. Baldasseroni S, Opasich C, Gorini M, et al. Left bundle-branch block is associated with increased 1-year sudden and total mortality rate in 5517 outpatients with congestive heart failure: a report from the Italian network on congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 2002; 143:398–405.

Article24. Stellbrink C, Nowak B. The importance of being synchronous: on the prognostic value of ventricular conduction delay in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002; 40:2031–2033.25. Foster AH, Gold MR, McLaughlin JS. Acute hemodynamic effects of atrio-biventricular pacing in humans. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995; 59:294–300.

Article26. Leclercq C, Cazeau S, Le Breton H, et al. Acute hemodynamic effects of biventricular DDD pacing in patients with end-stage heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998; 32:1825–1831.

Article27. Cazeau S, Ritter P, Lazarus A, et al. Multisite pacing for end-stage heart failure: early experience. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1996; 19:1748–1757.

Article28. Auricchio A, Stellbrink C, Block M, et al. Effect of pacing chamber and atrioventricular delay on acute systolic function of paced patients with congestive heart failure. The Pacing Therapies for Congestive Heart Failure Study Group. The Guidant Congestive Heart Failure Research Group. Circulation. 1999; 99:2993–3001.29. Cazeau S, Leclercq C, Lavergne T, et al. Effects of multisite biventricular pacing in patients with heart failure and intraventricular conduction delay. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344:873–880.

Article30. Anand IS, Carson P, Galle E, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy reduces the risk of hospitalizations in patients with advanced heart failure: results from the Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing and Defibrillation in Heart Failure (COMPANION) trial. Circulation. 2009; 119:969–977.31. Stellbrink C, Breithardt OA, Franke A, et al. Impact of cardiac resynchronization therapy using hemodynamically optimized pacing on left ventricular remodeling in patients with congestive heart failure and ventricular conduction disturbances. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 38:1957–1965.32. European Heart Rhythm Association; European Society of Cardiology; Heart Rhythm Society, et al. 2012 EHRA/HRS expert consensus statement on cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure: implant and follow-up recommendations and management. Heart Rhythm. 2012; 9:1524–1576.33. Stavrakis S, Lazzara R, Thadani U. The benefit of cardiac resynchronization therapy and QRS duration: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012; 23:163–168.

Article34. Kang SH, Oh IY, Kang DY, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy and QRS duration: systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30:24–33.

Article35. Boriani G, Nesti M, Ziacchi M, Padeletti L. Cardiac resynchronization therapy: an overview on guidelines. Heart Fail Clin. 2017; 13:117–137.36. Chung ES, Leon AR, Tavazzi L, et al. Results of the predictors of response to CRT (PROSPECT) trial. Circulation. 2008; 117:2608–2616.

Article37. Lee SH, Park SJ, Kim JS, Shin DH, Cho DK, On YK. Mid-term outcomes in patients implanted with cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2014; 29:1651–1657.

Article38. Uhm JS, Oh J, Cho IJ, et al. Left ventricular end-systolic volume can predict 1-year hierarchical clinical composite end point in patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy. Yonsei Med J. 2019; 60:48–55.

Article39. Maggioni AP, Anker SD, Dahlström U, et al. Are hospitalized or ambulatory patients with heart failure treated in accordance with European Society of Cardiology guidelines? Evidence from 12,440 patients of the ESC heart failure long-term registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013; 15:1173–1184.40. Randolph TC, Hellkamp AS, Zeitler EP, et al. Utilization of cardiac resynchronization therapy in eligible patients hospitalized for heart failure and its association with patient outcomes. Am Heart J. 2017; 189:48–58.

Article41. Lund LH, Benson L, Ståhlberg M, et al. Age, prognostic impact of QRS prolongation and left bundle branch block, and utilization of cardiac resynchronization therapy: findings from 14,713 patients in the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014; 16:1073–1081.

Article42. Bank AJ, Gage RM, Olshansky B. On the underutilization of cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Card Fail. 2014; 20:696–705.

Article43. Hsu LF, Jaïs P, Sanders P, et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004; 351:2373–2383.

Article44. Khan MN, Jaïs P, Cummings J, et al. Pulmonary-vein isolation for atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:1778–1785.45. Di Biase L, Mohanty P, Mohanty S, et al. Ablation versus amiodarone for treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with congestive heart failure and an implanted device: results from the AATAC multicenter randomized trial. Circulation. 2016; 133:1637–1644.46. Marrouche NF, Brachmann J, Andresen D, et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:417–427.

Article47. Curtis AB, Worley SJ, Adamson PB, et al. Biventricular pacing for atrioventricular block and systolic dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368:1585–1593.

Article48. Linde CM, Normand C, Bogale N, et al. Upgrades from a previous device compared to de novo cardiac resynchronization therapy in the European Society of Cardiology CRT survey II. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018; 20:1457–1468.

Article49. Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, et al. Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012; 125:1928–1952.50. Bordachar P, Alonso C, Anselme F, et al. Addition of a second LV pacing site in CRT nonresponders rationale and design of the multicenter randomized V(3) trial. J Card Fail. 2010; 16:709–713.

Article51. Zanon F, Baracca E, Pastore G, et al. Multipoint pacing by a left ventricular quadripolar lead improves the acute hemodynamic response to CRT compared with conventional biventricular pacing at any site. Heart Rhythm. 2015; 12:975–981.

Article52. Pappone C, Ćalović Ž, Vicedomini G, et al. Improving cardiac resynchronization therapy response with multipoint left ventricular pacing: twelve-month follow-up study. Heart Rhythm. 2015; 12:1250–1258.

Article53. Leclercq C, Burri H, Curnis A, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy non-responder to responder conversion rate in the more response to cardiac resynchronization therapy with MultiPoint Pacing (MORE-CRT MPP) study: results from phase I. Eur Heart J. 2019.

Article54. Leclercq C, Burri H, Curnis A, et al. Rationale and design of a randomized clinical trial to assess the safety and efficacy of multipoint pacing therapy: MOre REsponse on Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy with MultiPoint Pacing (MORE-CRT MPP-PHASE II). Am Heart J. 2019; 209:1–8.

Article55. Brignole M, Auricchio A, Baron-Esquivias G, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the task force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Eur Heart J. 2013; 34:2281–2329.56. Tolosana JM, Brugada J. Optimizing cardiac resynchronization therapy devices in follow-up to improve response rates and outcomes. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2019; 11:89–98.

Article57. Altman RK, Parks KA, Schlett CL, et al. Multidisciplinary care of patients receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy is associated with improved clinical outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:2181–2188.

Article58. Ruschitzka F, Abraham WT, Singh JP, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy in heart failure with a narrow QRS complex. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:1395–1405.

Article59. Obeng-Gyimah E, Nazarian S. Cardiac magnetic resonance as a tool to assess dyssynchrony. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2019; 11:49–53.

Article60. Leyva F, Foley PW, Chalil S, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy guided by late gadolinium-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011; 13:29.

Article61. Khan FZ, Virdee MS, Palmer CR, et al. Targeted left ventricular lead placement to guide cardiac resynchronization therapy: the TARGET study: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 59:1509–1518.62. Sommer A, Kronborg MB, Nørgaard BL, et al. Multimodality imaging-guided left ventricular lead placement in cardiac resynchronization therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016; 18:1365–1374.

Article63. Singh JP, Berger RD, Doshi RN, et al. Rationale and design for ENHANCE CRT: QLV implant strategy for non-left bundle branch block patients. ESC Heart Fail. 2018; 5:1184–1190.

Article64. Auricchio A, Delnoy PP, Butter C, et al. Feasibility, safety, and short-term outcome of leadless ultrasound-based endocardial left ventricular resynchronization in heart failure patients: results of the wireless stimulation endocardially for CRT (WiSE-CRT) study. Europace. 2014; 16:681–688.

Article65. Derval N, Steendijk P, Gula LJ, et al. Optimizing hemodynamics in heart failure patients by systematic screening of left ventricular pacing sites: the lateral left ventricular wall and the coronary sinus are rarely the best sites. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55:566–575.66. Shetty AK, Sohal M, Chen Z, et al. A comparison of left ventricular endocardial, multisite, and multipolar epicardial cardiac resynchronization: an acute haemodynamic and electroanatomical study. Europace. 2014; 16:873–879.

Article67. Morgan JM, Biffi M, Gellér L, et al. ALternate Site Cardiac ResYNChronization (ALSYNC): a prospective and multicentre study of left ventricular endocardial pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:2118–2127.

Article68. Reddy VY, Miller MA, Neuzil P, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy with wireless left ventricular endocardial pacing: the SELECT-LV study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:2119–2129.69. Vijayaraman P, Bordachar P, Ellenbogen KA. The continued search for physiological pacing: where are we now? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:3099–3114.70. Lustgarten DL, Calame S, Crespo EM, Calame J, Lobel R, Spector PS. Electrical resynchronization induced by direct His-bundle pacing. Heart Rhythm. 2010; 7:15–21.

Article71. Lustgarten DL. His bundle pacing: getting on the learning curve. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2018; 10:491–494.72. Mar PL, Devabhaktuni SR, Dandamudi G. His bundle pacing in heart failure-concept and current data. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2019; 16:47–56.

Article73. Ajijola OA, Upadhyay GA, Macias C, Shivkumar K, Tung R. Permanent His-bundle pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy: initial feasibility study in lieu of left ventricular lead. Heart Rhythm. 2017; 14:1353–1361.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Myocardial Dyssynchronicity and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

- Successful Placement of a Left Ventricular Pacing Lead Despite Coronary Sinus Dissection During Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

- Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

- Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

- The Role of Echocardiography in Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy