Pediatr Infect Vaccine.

2019 Apr;26(1):32-41. 10.14776/piv.2019.26.e4.

Childhood Tuberculosis Contact Investigation and Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: a Single Center Study, 2014–2017

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, the Republic of Korea. eycho@cnuh.co.kr

- 2Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, the Republic of Korea.

- KMID: 2443163

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14776/piv.2019.26.e4

Abstract

- PURPOSE

In order to prevent tuberculosis transmission early, it is important to diagnose and treat tuberculosis infection by investigating people who have contact with patients with active tuberculosis.

METHODS

From July 2014 to June 2017, the intrafamilial childhood contacts of the patients who were diagnosed with active tuberculosis at Chungnam National University Hospital were investigated for the presence of tuberculosis infection. We also retrospectively analyzed the treatment status of children treated with latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) during the same period.

RESULTS

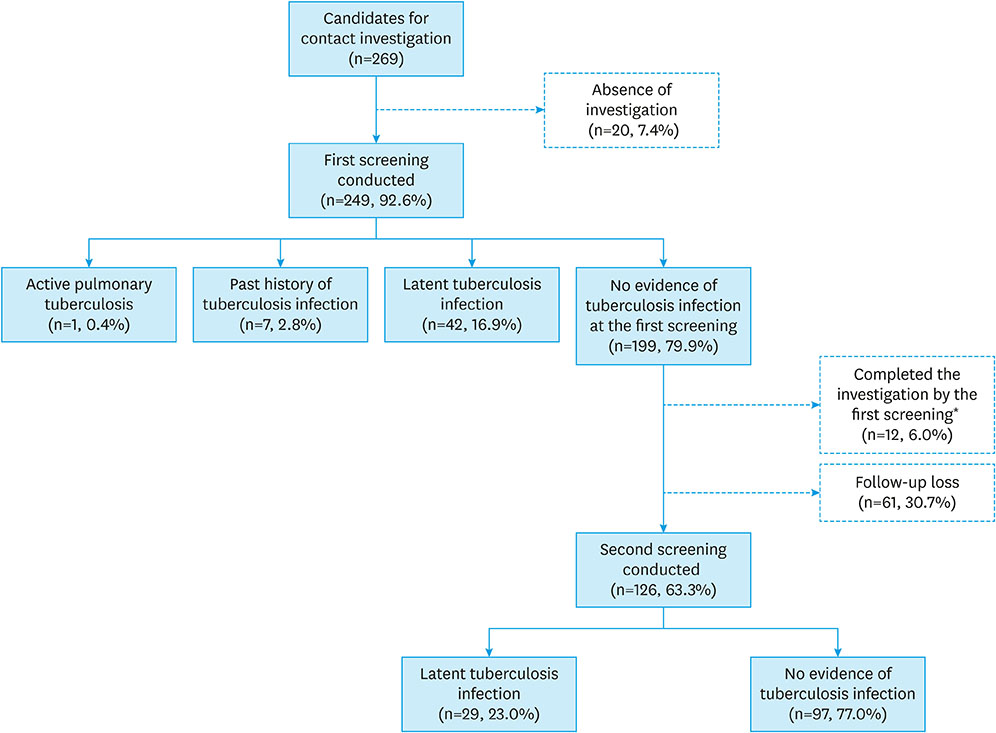

Among the 269 children who had intrafamilial contact with active tuberculosis patient, 20 (7.4%) did not receive any screening. At the first screening, one (0.4%) was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis, seven (2.8%) had a previous history of tuberculosis infection, and 42 patients (16.9%) were diagnosed with LTBI. At the second screening, 29 patients (11.6%) were diagnosed with LTBI, and 61 patients did not finish the investigation. Only 188 (69.9%) out of 269 patients completed the investigation. Ninety patients received treatment for LTBI and 83 patients (92.2%) completed the treatment, of which 18 patients had side effects such as rash, fatigue, and gastrointestinal symptoms. However, there were no serious side effects requiring treatment discontinuation.

CONCLUSIONS

The completion rate of childhood tuberculosis contact investigation was low, but the completion rate of LTBI treatment was high in children without serious side effects. In order to prevent and manage the spread of tuberculosis, active private-public partnership efforts and education of the patient and guardian are needed.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. BOX 1.1. Basic facts about TB & Chapter 1. Introduction. In: Global tuberculosis report 2018 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;2018. 6–7. cited 2018 Oct 22. Available from: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en.2. World Health Organization. TABLE A4.1. TB incidence estimates, 2017 & TABLE A4.2. Estimates of TB mortality, 2017. Global tuberculosis report 2018 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;2018. 245–252. cited 2018 Oct 22. Available from: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en.3. Joint Committee for the Revision of Korean Guidelines for Tuberculosis. The Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Tuberculosis Control Program. In: Korean guidelines for tuberculosis, 3rd ed [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2017. 219–221. cited 2018 Oct 22. Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/together/CdcKrTogether0302.jsp?menuIds=HOME006-MNU2804-MNU3027-MNU2979&cid=138077.4. Marais BJ, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, Hesseling AC, Obihara CC, Nelson LJ, et al. The clinical epidemiology of childhood pulmonary tuberculosis: a critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004; 8:278–285.5. Joint Committee for the Revision of Korean Guidelines for Tuberculosis. The Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis in children and adolescents. In: Korean guidelines for tuberculosis, 3rd ed [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2017. 122–157. cited 2018 Oct 22. Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/together/CdcKrTogether0302.jsp?menuIds=HOME006-MNU2804-MNU3027-MNU2979&cid=138077.6. Marais BJ, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, Hesseling AC, Obihara CC, Starke JJ, et al. The natural history of childhood intra-thoracic tuberculosis: a critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004; 8:392–402.7. Kim JH, Yim JJ. Achievements in and challenges of tuberculosis control in South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015; 21:1913–1920.

Article8. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018 National tuberculosis program guideline [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2018. cited 2018 Oct 22. Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/together/CdcKrTogether0302.jsp?menuIds=HOME006-MNU2804-MNU3027-MNU2979&cid=138005.9. Joint Committee for the Revision of Korean Guidelines for Tuberculosis. Korean guidelines for tuberculosis, 2nd edition [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2014. cited 2018 Oct 22. Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/together/CdcKrTogether0302.jsp?menuIds=HOME006-MNU2804-MNU3027-MNU2979&cid=138235.10. Lee MH, Sung JJ, Eun BW, Cho HK. Survey of secondary infections within the households of newly diagnosed tuberculosis patients. Pediatr Infect Vaccine. 2015; 22:7–15.

Article11. Lee TJ, Kim EK, Jeong HC. Outcomes of child contact investigations of active pulmonary tuberculosis patients: a single center experience from 2012 to 2014. Pediatr Infect Vaccine. 2015; 22:91–96.

Article12. Min DH, Wy HH, Shim JW, Kim DS, Jung HL, Park MS, et al. Risk factors for latent tuberculosis in children who had close contact to households with pulmonary tuberculosis. Allergy Asthma Respir Dis. 2017; 5:105–110.

Article13. Frydenberg AR, Graham SM. Toxicity of first-line drugs for treatment of tuberculosis in children: review. Trop Med Int Health. 2009; 14:1329–1337.

Article14. Ena J, Valls V. Short-course therapy with rifampin plus isoniazid, compared with standard therapy with isoniazid, for latent tuberculosis infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 40:670–676.

Article15. Spyridis NP, Spyridis PG, Gelesme A, Sypsa V, Valianatou M, Metsou F, et al. The effectiveness of a 9-month regimen of isoniazid alone versus 3- and 4-month regimens of isoniazid plus rifampin for treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in children: results of an 11-year randomized study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45:715–722.

Article16. Schechter M, Zajdenverg R, Falco G, Barnes GL, Faulhaber JC, Coberly JS, et al. Weekly rifapentine/isoniazid or daily rifampin/pyrazinamide for latent tuberculosis in household contacts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006; 173:922–926.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Treatment of latent tuberculous infection in children and adolescent

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection in Healthcare Workers

- Characteristics of tuberculosis in children and adolescents

- Update on Tuberculosis in Children and Adolescents

- Survey of Secondary Infections within the Households of Newly Diagnosed Tuberculosis Patients