Intest Res.

2018 Oct;16(4):619-627. 10.5217/ir.2018.00013.

Rates of metachronous adenoma after curative resection for left-sided or right-sided colon cancer

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Medicine Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. waikleung@hku.hk

- 2Department of Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

- KMID: 2434164

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2018.00013

Abstract

- BACKGROUND/AIMS

We determined the rates of metachronous colorectal neoplasm in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients after resection for right (R)-sided or left (L)-sided cancer.

METHODS

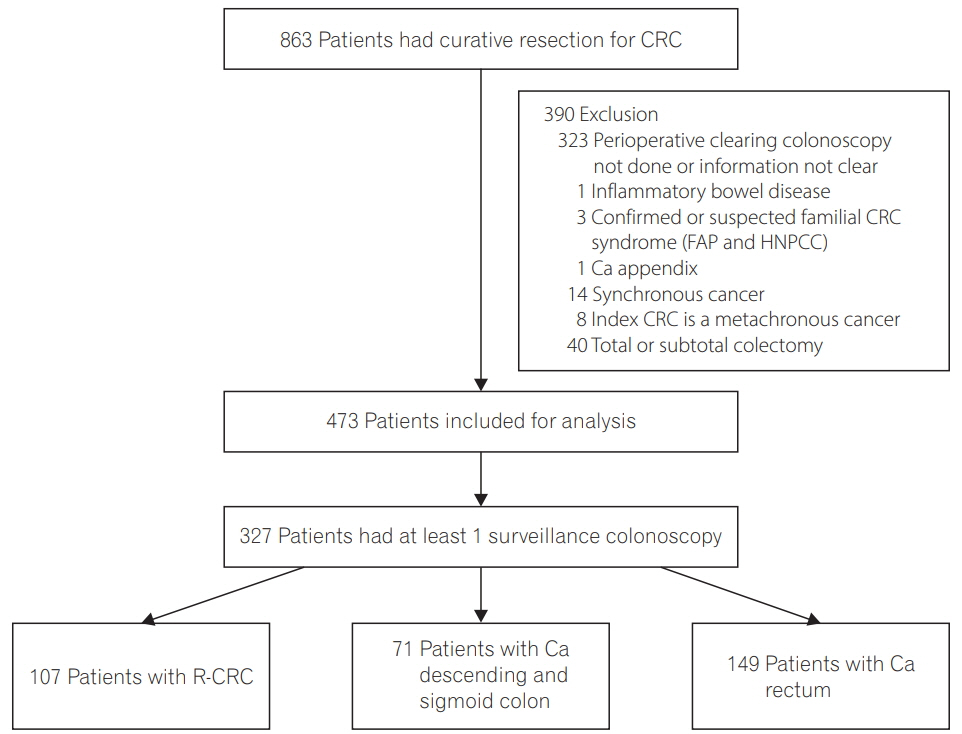

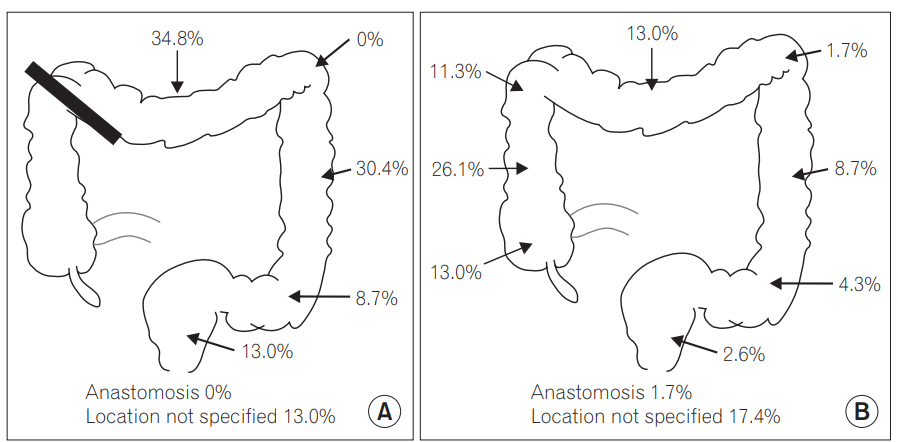

Consecutive CRC patients who had undergone surgical resection for curative intent in our hospital between 2001 and 2004 were identified. R-sided colonic cancers refer to cancer proximal to splenic flexure whereas L-sided cancers include rectal cancers. Patients were included only if they had a clearing colonoscopy performed either before or within 6 months after the operation. Findings of surveillance colonoscopy performed up to 5 years after colonic resection were included in the analysis.

RESULTS

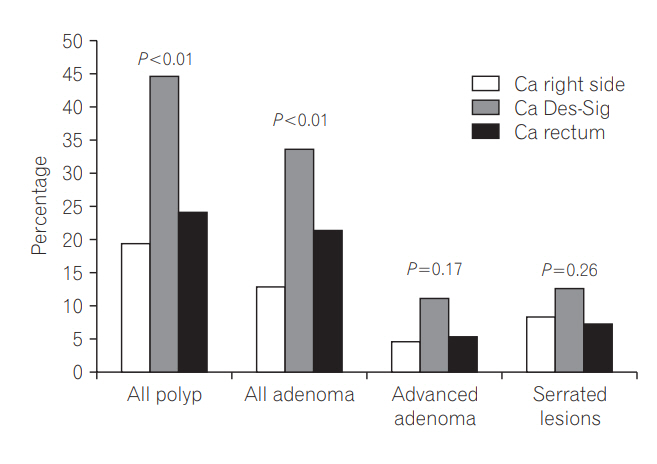

Eight hundred and sixty-three CRC patients underwent curative surgical resection during the study period. Three hundred and twenty-seven patients (107 R-sided and 220 L-sided) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and had at least 1 postoperative surveillance colonoscopy performed. The proportion of patients who had polyp and adenoma on surveillance colonoscopy was significantly higher among patients with L-sided than R-sided cancers (polyps: 30.9% vs. 19.6%, P=0.03; adenomas: 25.5% vs. 13.1%, P=0.01). The mean number of adenoma per patient on surveillance colonoscopy was also higher for patients with L-sided than R-sided tumors (0.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.37-0.68 vs. 0.22; 95% CI, 0.08-0.35; P < 0.01). Multivariate analysis showed that L-sided cancers, age, male gender and longer follow-up were independent predictors of adenoma detection on surveillance colonoscopy.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients with Lsided cancer had a higher rate of metachronous polyps and adenoma than those with R-sided cancer on surveillance colonoscopy.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Pita-Fernández S, Alhayek-Aí M, González-Martín C, López-Calviño B, Seoane-Pillado T, Pértega-Díaz S. Intensive follow-up strategies improve outcomes in nonmetastatic colorectal cancer patients after curative surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2015; 26:644–656.

Article2. Fisher DA, Jeffreys A, Grambow SC, Provenzale D. Mortality and follow-up colonoscopy after colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003; 98:901–906.

Article3. Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012; 107:1315–1329.

Article4. Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2010; 138:2088–2100.

Article5. Hassan C, Gaglia P, Zullo A, et al. Endoscopic follow-up after colorectal cancer resection: an Italian multicentre study. Dig Liver Dis. 2006; 38:45–50.

Article6. Moon CM, Cheon JH, Choi EH, et al. Advanced synchronous adenoma but not simple adenoma predicts the future development of metachronous neoplasia in patients with resected colorectal cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010; 44:495–501.

Article7. Kawai K, Sunami E, Tsuno NH, Kitayama J, Watanabe T. Polyp surveillance after surgery for colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012; 27:1087–1093.

Article8. Rennert G, Robinson E, Rennert HS, Neugut AI. Clinical characteristics of metachronous colorectal tumors. Int J Cancer. 1995; 60:743–747.

Article9. Gervaz P, Bucher P, Neyroud-Caspar I, Soravia C, Morel P. Proximal location of colon cancer is a risk factor for development of metachronous colorectal cancer: a population-based study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005; 48:227–232.

Article10. Mulder SA, Kranse R, Damhuis RA, Ouwendijk RJ, Kuipers EJ, van Leerdam ME. The incidence and risk factors of metachronous colorectal cancer: an indication for follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012; 55:522–531.11. Ringland CL, Arkenau HT, O’Connell DL, Ward RL. Second primary colorectal cancers (SPCRCs): experiences from a large Australian Cancer Registry. Ann Oncol. 2010; 21:92–97.12. Fuccio L, Spada C, Frazzoni L, et al. Higher adenoma recurrence rate after left- versus right-sided colectomy for colon cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015; 82:337–343.13. Kahi CJ, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colonoscopy surveillance after colorectal cancer resection: recommendations of the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150:758–768. e11.14. Meyerhardt JA, Mangu PB, Flynn PJ, et al. Follow-up care, surveillance protocol, and secondary prevention measures for survivors of colorectal cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:4465–4470.

Article15. Labianca R, Nordlinger B, Beretta GD, Brouquet A, Cervantes A; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary colon cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, adjuvant treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010; 21 Suppl 5:v70–v77.

Article16. Glimelius B, Påhlman L, Cervantes A; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010; 21 Suppl 5:v82–v86.

Article17. Chan EW, Lau WC, Leung WK, et al. Prevention of dabigatran-related gastrointestinal bleeding with gastroprotective agents: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2015; 149:586–595. e3.

Article18. Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer;2002.19. Leung WK, Lo OS, Liu KS, et al. Detection of colorectal adenoma by narrow band imaging (HQ190) vs. high-definition white light colonoscopy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 109:855–863.

Article20. Snover D, Ahnen DJ, Burt RW, et al. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum and serrated (“hyperplastic”) polyposis. In : Bozman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, editors. WHO classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag;2010. p. 160–165.21. Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, Dufrayne F, Bergman G. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-Soda. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000; 52:346–352.

Article22. Samadder NJ, Curtin K, Tuohy TM, et al. Characteristics of missed or interval colorectal cancer and patient survival: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2014; 146:950–960.

Article23. Bressler B, Paszat LF, Chen Z, Rothwell DM, Vinden C, Rabeneck L. Rates of new or missed colorectal cancers after colonoscopy and their risk factors: a population-based analysis. Gastroenterology. 2007; 132:96–102.

Article24. le Clercq CM, Bouwens MW, Rondagh EJ, et al. Postcolonoscopy colorectal cancers are preventable: a population-based study. Gut. 2014; 63:957–963.

Article25. Robertson DJ, Lieberman DA, Winawer SJ, et al. Colorectal cancers soon after colonoscopy: a pooled multicohort analysis. Gut. 2014; 63:949–956.

Article26. Rex DK, Cutler CS, Lemmel GT, et al. Colonoscopic miss rates of adenomas determined by back-to-back colonoscopies. Gastroenterology. 1997; 112:24–28.

Article27. Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2015; 21:1350–1356.28. Thanki K, Nicholls ME, Gajjar A, et al. Consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer and their clinical implications. Int Biol Biomed J. 2017; 3:105–111.29. Rabeneck L, Davila JA, El-Serag HB. Is there a true “shift” to the right colon in the incidence of colorectal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003; 98:1400–1409.

Article30. Cucino C, Buchner AM, Sonnenberg A. Continued rightward shift of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002; 45:1035–1040.

Article31. Obrand DI, Gordon PH. Continued change in the distribution of colorectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1998; 85:246–248.

Article32. Patel K, Hoffman NE. The anatomical distribution of colorectal polyps at colonoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001; 33:222–225.

Article33. Klein JL, Okcu M, Preisegger KH, Hammer HF. Distribution, size and shape of colorectal adenomas as determined by a colonoscopist with a high lesion detection rate: influence of age, sex and colonoscopy indication. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016; 4:438–448.

Article34. Salem ME, Weinberg BA, Xiu J, et al. Comparative molecular analyses of left-sided colon, right-sided colon, and rectal cancers. Oncotarget. 2017; 8:86356–86368.

Article35. Brennan CA, Garrett WS. Gut microbiota, inflammation, and colorectal cancer. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2016; 70:395–411.

Article36. Purcell RV, Visnovska M, Biggs PJ, Schmeier S, Frizelle FA. Distinct gut microbiome patterns associate with consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2017; 7:11590.

Article37. Sze MA, Baxter NT, Ruffin MT 4th, Rogers MA, Schloss PD. Normalization of the microbiota in patients after treatment for colonic lesions. Microbiome. 2017; 5:150.

Article38. Shitoh K, Konishi F, Miyakura Y, Togashi K, Okamoto T, Nagai H. Microsatellite instability as a marker in predicting metachronous multiple colorectal carcinomas after surgery: a cohort-like study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002; 45:329–333.

Article39. le Clercq CM, Winkens B, Bakker CM, et al. Metachronous colorectal cancers result from missed lesions and non-compliance with surveillance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015; 82:325–333. e2.

Article40. Lebwohl B, Kastrinos F, Glick M, Rosenbaum AJ, Wang T, Neugut AI. The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 73:1207–1214.

Article41. Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 61:378–384.

Article42. Chen SC, Rex DK. Endoscopist can be more powerful than age and male gender in predicting adenoma detection at colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007; 102:856–861.

Article43. Subramanian V, Mannath J, Hawkey CJ, Ragunath K. High definition colonoscopy vs. standard video endoscopy for the detection of colonic polyps: a meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2011; 43:499–505.

Article44. Lee TJ, Blanks RG, Rees CJ, et al. Longer mean colonoscopy withdrawal time is associated with increased adenoma detection: evidence from the Bowel Cancer Screening Programme in England. Endoscopy. 2013; 45:20–26.

Article45. Ross WA, Thirumurthi S, Lynch PM, et al. Detection rates of premalignant polyps during screening colonoscopy: time to revise quality standards? Gastrointest Endosc. 2015; 81:567–574.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Prognosis and Recurrence Pattern of Right- and Left-Sided Colon Cancer in Stage II, Stage III, and Liver Metastasis After Curative Resection

- Short-Term Outcome of Curative One-Stage Laparoscopic Resection for Obstructive Left-Sided Colon Cancers Followed by Stent Insertion: Comparative Study with Non-Obstructive Left-Sided Colon Cancers

- Laterality: Right-Sided and Left-Sided Colon Cancer

- Laterality: Immunological Differences Between Right-Sided and Left-Sided Colon Cancer

- Oncological Safety of a Metallic Stent for a Left-sided Obstructive Colorectal Carcinoma