J Dent Rehabil Appl Sci.

2018 Dec;34(4):290-296. 10.14368/jdras.2018.34.4.290.

Evaluation of polymerization ability of resin-based materials used for teeth splinting

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Conservative Dentistry, College of Dentistry, Gangneung-Wonju National University, Gangneung, Republic of Korea. drbozon@gwnu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Periodontology, Research Institute for Oral Sciences, College of Dentistry, Gangneung-Wonju National University, Gangneung, Republic of Korea.

- KMID: 2432365

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14368/jdras.2018.34.4.290

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The aim of this study was to evaluate the polymerization ability of resin-based materials used for teeth splinting according to the thickness of cure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

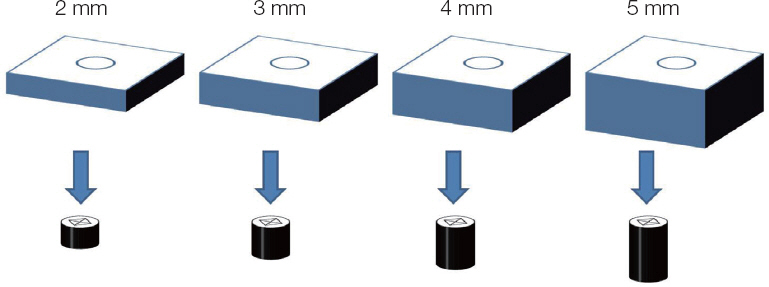

For this study, the Light-Fix and G-FIX developed for resinous splinting materials and the G-aenial Universal Flo, the high-flowable composite resin available as restorative and splinting material, were used. Ten specimens of the thickness of 2, 3, 4 and 5 mm and 5 mm in diameter for each composite resin (total 120) were prepared. The microhardness of top and bottom surfaces for each specimen was measured by the Vickers hardness testing machine. The polymerization ability of the composite resin for each thickness was statistically analyzed using independent T-test at a 0.05 level of significance.

RESULTS

There was no difference of polymerization ability regardless of the thickness in the Light-Fix and G-FIX. The G-aenial Universal Flo showed significantly low polymerization ability from the thickness of the 3 mm (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION

The Light-Fix and G-FIX, which are resin-based materials used for teeth splinting, are expected to be suitable for light curing up to 5 mm in thickness.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Bernal G, Carvajal JC, Muñoz-Viveros CA. A Review of the Clinical Management of Mobile Teeth. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2002; 3:10–22. PMID: 12444399.2. Watts A, Addy M. Tooth discolouration and staining: a review of the literature. Br Dent J. 2001; 190:309–16. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800959. PMID: 11325156.3. Ferencz JL. Splinting. Dent Clin North Am. 1987; 31:383–93. PMID: 3301434.4. Smales RJ, Webster DA. Restoration deterioration related to later failure. Oper Dent. 1993; 18:130–7. PMID: 8152980.5. Burcak Cengiz S, Stephan Atac A, Cehreli ZC. Biomechanical effects of splint types on traumatized tooth: a photoelastic stress analysis. Dent Traumatol. 2006; 22:133–8. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2006.00339.x. PMID: 16643288.6. Oikarinen K. Comparison of the flexibility of various splinting methods for tooth fixation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988; 17:125–7. DOI: 10.1016/S0901-5027(88)80166-8. PMID: 3133422.7. Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Mejàre I, Cvek M. Healing of 400 intra-alveolar root fractures. 2. Effect of treatment factors such as treatment delay, repositioning, splinting type and period and antibiotics. Dent Traumatol. 2004; 20:203–11. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2004.00278.x. PMID: 15245519.8. Neaverth EJ, Georig AC. Technique and rationale for splinting. J Am Dent Assoc. 1980; 100:56–63. DOI: 10.14219/jada.archive.1980.0026. PMID: 6101280.9. Kahler B, Heithersay GS. An evidence-based appraisal of splinting luxated, avulsed and rootfractured teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2008; 24:2–10. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2006.00480.x. PMID: 18173657.10. Mazzoleni S, Meschia G, Cortesi R, Bressan E, Tomasi C, Ferro R, Stellini E. In vitro comparison of the flexibility of different splint systems used in dental traumatology. Dent Traumatol. 2010; 26:30–6. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2009.00843.x. PMID: 20089059.11. Liu X, Zhang Y, Zhou Z, Ma S. Retrospective study of combined splinting restorations in the aesthetic zone of periodontal patients. Br Dent J. 2016; 220:241–7. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.178. PMID: 26964599.12. Aggstaller H, Beuer F, Edelhoff D, Rammelsberg P, Gernet W. Long-term clinical performance of resin-bonded fixed partial dentures with retentive preparation geometry in anterior and posterior areas. J Adhes Dent. 2008; 10:301–6. PMID: 18792701.13. Ferracane JL. Correlation between hardness and degree of conversion during the setting reaction of unfilled dental restorative resins. Dent Mater. 1985; 1:11–4. DOI: 10.1016/S0109-5641(85)80058-0. PMID: 3160625.14. Vankerckhoven H, Lambrechts P, van Beylen M, Davidson CL, Vanherle G. Unreacted Methacrylate Groups on the Surfaces of Composite Resins. J Dent Res. 1982; 61:791–5. DOI: 10.1177/00220345820610062801. PMID: 7045184.15. Cook WD, Standish PM. Cure of resin based restorative materials. II. White light photopolymerized resins. Aust Dent J. 1983; 28:307–11. DOI: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1983.tb02491.x. PMID: 6582829.16. Gonçalves F, Pfeifer CC, Stansbury JW, Newman SM, Braga RR. Influence of matrix composition on polymerization stress development of experimental composites. Dent Mater. 2010; 26:697–703. DOI: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.03.014. PMID: 20381138.17. Pilo R, Cardash HS. Post-irradiation polymerization of different anterior and posterior visible lightactivated resin composites. Dent Mater. 1992; 8:299–304. DOI: 10.1016/0109-5641(92)90104-K. PMID: 1303371.18. Hofmann N, Papsthart G, Hugo B, Klaiber B. Comparison of photo-activation versus chemical or dual-curing of resin-based luting cements regarding flexural strength, modulus and surface hardness. J Oral Rehabil. 2001; 28:1022–8. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2001.00809.x. PMID: 11722718.19. Asmussen E. Factors affecting the quantity of remaining double bonds in restorative resin polymers. Scand J Dent Res. 1982; 90:490–6. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1982.tb00767.x. PMID: 6218604.20. Rueggeberg FA, Craig RG. Correlation of parameters used to estimate monomer conversion in a light-cured composite. J Dent Res. 1988; 67:932–7. DOI: 10.1177/00220345880670060801. PMID: 3170905.21. Abed YA, Sabry HA, Alrobeigy NA. Degree of conversion and surface hardness of bulk-fill composite versus incremental-fill composite. Tanta Dent J. 2015; 12:71–80. DOI: 10.1016/j.tdj.2015.01.003.22. Moraes LG, Rocha RS, Menegazzo LM, de Areaújo EB, Yukimiti K, Moraes JC. Infrared spectroscopy: a tool for determination of the degree of conversion in dental composites. J Appl Oral Sci. 2008; 16:145–9. DOI: 10.1590/S1678-77572008000200012. PMID: 19089207.23. Gajewski VE, Pfeifer CS, Fróes-Salgado NR, Boaro LC, Braga RR. Monomers used in resin composites: degree of conversion, mechanical properties and water sorption/solubility. Braz Dent J. 2012; 23:508–14. DOI: 10.1590/S0103-64402012000500007. PMID: 23306226.24. Cook WD. Factors affecting the depth of cure of UVpolymerized composites. J Dent Res. 1980; 59:800–8. DOI: 10.1177/00220345800590050901. PMID: 6928870.25. DeWald JP, Ferracane JL. A comparison of four modes of evaluating depth of cure of light-activated composites. J Dent Res. 1987; 66:727–30. DOI: 10.1177/00220345870660030401. PMID: 3475304.26. Asmussen E. Restorative resins: hardness and strength vs. quantity of remaining double bonds. Scand J Dent Res. 1982; 90:484–9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1982.tb00766.x. PMID: 6218603.27. Noh T, Song E, Park S, Pyo A, Kwon Y, Kim J, Kim S, Jeong T. Comparison of the Mechanical Properties between Bulk-fill and Conventional Composites. J Korean Acad Pediatr Dent. 2016; 43:365–73. DOI: 10.5933/JKAPD.2016.43.4.365.28. Fonseca RB, de Almeida LN, Mendes GA, Kasuya AV, Favarão IN, de Paula MS. Effect of short glass fiber/filler particle proportion on flexural and diametral tensile strength of a novel fiber-reinforced composite. J Prosthodont Res. 2016; 60:47–53. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpor.2015.10.004. PMID: 26589845.29. Ilie N, Jelen E, Clementino-Luedemann T, Hickel R. Low-shrinkage composite for dental application. Dent Mater J. 2007; 26:149–55. DOI: 10.4012/dmj.26.149. PMID: 17621928.30. Loguercio AD, Reis A, Schroeder M, Balducci I, Versluis A, Ballester RY. Polymerization shrinkage: effects of boundary conditions and filling technique of resin composite restorations. J Dent. 2004; 32:459–70. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.02.010. PMID: 15240064.31. de Gee AJ, ten Harkel-Hagenaar E, Davidson CL. Color dye for identification of incompletely cured composite resins. J Prosthet Dent. 1984; 52:626–31. DOI: 10.1016/0022-3913(84)90129-X. PMID: 6208358.32. Son SA, Kim HC, Hur B, Seol HJ, Kwon YH, Kim HI, Park JK. Influence of Resin Thickness on the Degree of Conversion and Microhardness of Silorane-based Composite Resin. Korea J Dent Mater. 2012; 39:57–64.33. Hofmann N, Papsthart G, Hugo B, Klaiber B. Comparison of photo-activation versus chemical or dual-curing of resin-based luting cements regarding flexural strength, modulus and surface hardness. J Oral Rehabil. 2001; 28:1022–8. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2001.00809.x. PMID: 11722718.34. Ruyter IE, Oysaed H. Conversion in different depths of ultraviolet and visible light activated composite materials. Acta Odontol Scand. 1982; 40:179–92. DOI: 10.3109/00016358209012726. PMID: 6957140.35. Yoo JI, Kim SY, Batbayar B, Kim JW, Park SH, Cho KM. Comparison of flexural strength and modulus of elasticity in several resinous teeth splinting materials. J Dent Rehabil Appl Sci. 2016; 32:169–75. DOI: 10.14368/jdras.2016.32.3.169.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Accuracy of five implant impression technique: effect of splinting materials and methods

- Evaluation of polymerization shrinkage stress in silorane-based composites

- Microleakage and Shear Bond Strength of Biodentine at Different Setting Time

- Polymerization shrinkage, hygroscopic expansion and microleakage of resin-based temporary filling materials

- Effects of immediate and delayed light activation on the polymerization shrinkage-strain of dual-cure resin cements