Lab Med Online.

2019 Jan;9(1):1-5. 10.3343/lmo.2019.9.1.1.

Analytical Performance of INNOVANCE Free Protein S Antigen on Sysmex CS-5100

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Laboratory Medicine, Ewha Womans University, College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. JungWonH@ewha.ac.kr

- 2Eone Laboratories, Incheon, Korea.

- KMID: 2430202

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3343/lmo.2019.9.1.1

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Protein S deficiency is a common cause of thrombophilia. Free protein S has been suggested as one of the best screening tests for this deficiency. We evaluated an immunoturbidimetric free protein S reagent, INNOVANCE Free Protein S Antigen (Free PS Ag; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Germany), using a CS-5100 coagulation analyzer (Sysmex, Japan).

METHODS

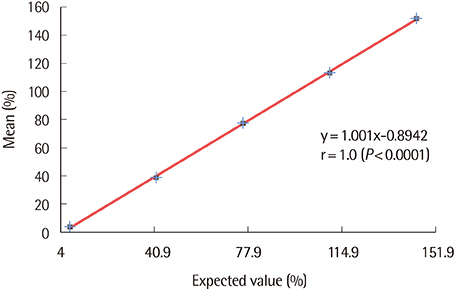

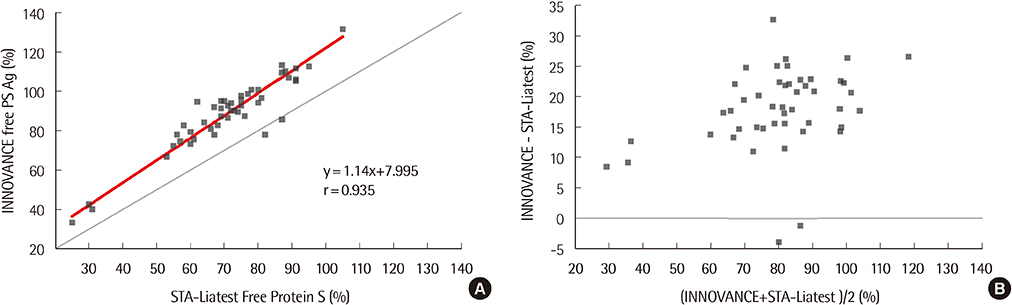

The performance of INNOVANCE Free PS Ag was evaluated according to the CLSI guidelines. Precision, linearity, and verification of reference intervals were examined. The INNOVANCE Free PS Ag was also compared by the STA-Liatest Free Protein S immunoturbidimetric assay (Diagnostica Stago, France).

RESULTS

The repeatability and within-laboratory imprecision of INNOVANCE Free PS Ag were 0.8% CV and 2.0% CV at the normal level, and 1.3% CV and 2.3% CV at the abnormally low level, respectively. This assay showed linearity from 4.0% to 151.9% (correlation coefficient r=1, P < 0.0001). Reference intervals for males and females were verified as acceptable. INNOVANCE Free PS Ag was comparable with STA-Liatest Free Protein S with a very high correlation (r=0.935, P < 0.0001). The results for the INNOVANCE antigen were higher.

CONCLUSIONS

The INNOVANCE Free PS Ag on a Sysmex CS-5100 coagulation analyzer has excellent analytical performance and is comparable with the STA-Liatest Free Protein S assay.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Ohga S, Ishiguro A, Takahashi Y, Shima M, Taki M, Kaneko M, et al. Protein C deficiency as the major cause of thrombophilias in childhood. Pediatr Int. 2013; 55:267–271.

Article2. Martinelli I, Mannucci PM, De Stefano V, Taioli E, Rossi V, Crosti F, et al. Different risks of thrombosis in four coagulation defects associated with inherited thrombophilia: a study of 150 families. Blood. 1998; 92:2353–2358.

Article3. Kitchens CS, Konkle BA, editors. Consultative hemostasis and thrombosis. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;2013. p. 212.4. Lee SY, Kim EK, Kim MS, Shin SH, Chang H, Jang SY, et al. The prevalence and clinical manifestation of hereditary thrombophilia in Korean patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolisms. PLoS ONE. 2017; 12:e0185785.

Article5. Crowley MP, Hunt BJ. Venous thromboembolism and thrombophilia testing. Medicine. 2017; 45:233–238.

Article6. Connors JM. Thrombophilia Testing and Venous Thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:1177–1187.

Article7. Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, Kasthuri R, Cushman M, Streiff M, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016; 41:154–164.

Article8. Marlar RA, Gausman JN. Protein S abnormalities: a diagnostic nightmare. Am J Hematol. 2011; 86:418–421.

Article9. Johnston AM, Aboud M, Morel-Kopp MC, Coyle L, Ward CM. Use of a functional assay to diagnose protein S deficiency; inappropriate testing yields equivocal results. Intern Med J. 2007; 37:409–411.

Article10. Cunningham MT, Olson JD, Chandler WL, Van Cott EM, Eby CS, Teruya J, et al. External quality assurance of antithrombin, protein C, and protein s assays: results of the College of American Pathologists proficiency testing program in thrombophilia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011; 135:227–232.

Article11. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. User verification of precision and estimation of bias; approved guideline—third ed. EP15-A3. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;2014.12. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Evaluation of the linearity of quantitative measurement procedures: a statistical approach; approved guideline. EP6-A. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;2003.13. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Defining, establishing, and verifying reference intervals in the clinical laboratory; approved guideline—third ed. EP28-A3c. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;2010.14. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Measurement procedure comparison and bias estimation using patient samples; approved guideline—third ed. EP09-A3. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;2013.15. Taylor R. Interpretation of the correlation coefficient: a basic review. J Diagn Med Sonogr. 1990; 6:35–39.

Article16. Mou E, Kwang H, Hom J, Shieh L, kumar A, Richman I, et al. Magnitude of potentially inappropriate thrombophilia testing in the inpatient hospital setting. J Hosp Med. 2017; 12:735–738.

Article17. De Maat MP, Van Schie M, Kluft C, Leebeek FW, Meijer P. Biological variation of hemostasis variables in thrombosis and bleeding: consequences for performance specifications. Clin Chem. 2016; 62:1639–1646.

Article18. Lijfering WM, Mulder R, ten Kate MK, Veeger NJ, Mulder AB, van der. Clinical relevance of decreased free protein S levels: results from a retrospective family cohort study involving 1143 relatives. Blood. 2009; 113:1225–1230.

Article19. Pintao MC, Ribeiro DD, Bezemer ID, Garcia AA, de Visser MC, Doggen CJ, et al. Protein S levels and the risk of venous thrombosis: results from the MEGA case-control study. Blood. 2013; 122:3210–3219.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Performance Evaluation of the CS-5100 Coagulation Analyzer for Special Coagulation Parameters

- Evaluation of Automated Platelet Aggregation Test Using a Sysmex CS-5100 Analyzer

- Evaluation of Automated Chemiluminescent Immunoanalyzer Immulite 2000

- Performance Evaluation of the Total Prostate- Specific Antigen (PSA), Free PSA, and [–2]proPSA Assay for Calculation of the Prostate Health Index Using the UniCel DxI 800 Analyzer

- Analytical Performance of Wako and Sekisui Clinical Chemistry Assays on Hitachi LABOSPECT 008