Cancer Res Treat.

2018 Oct;50(4):1388-1395. 10.4143/crt.2017.162.

Projection of Breast Cancer Burden due to Reproductive/Lifestyle Changes in Korean Women (2013-2030) Using an Age-Period-Cohort Model

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Public Health, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Institute of Health Services Research, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. ecpark@yuhs.ac

- 3Department of Hospital Administration, Graduate School of Public Health, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2424810

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2017.162

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The aim of this study was to estimate the burden of breast cancer that can be attributed to rapid lifestyle changes in South Korea in 2013-2030.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An age-period-cohort model was used to estimate the incidence and mortality. The Global Burden of Disease Study Group methodwas used to calculate the years of life lost and years lived with disability in breast cancer patients using a nationwide cancer registry. The population attributable riskswere calculated using meta-analyzed relative risk ratios and by assessing the prevalence of risk factors.

RESULTS

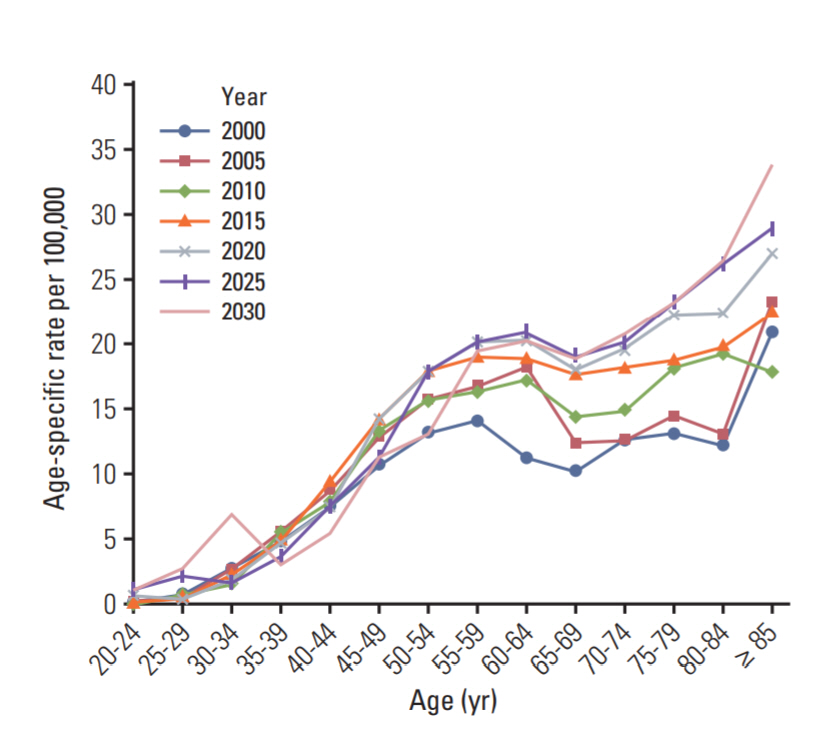

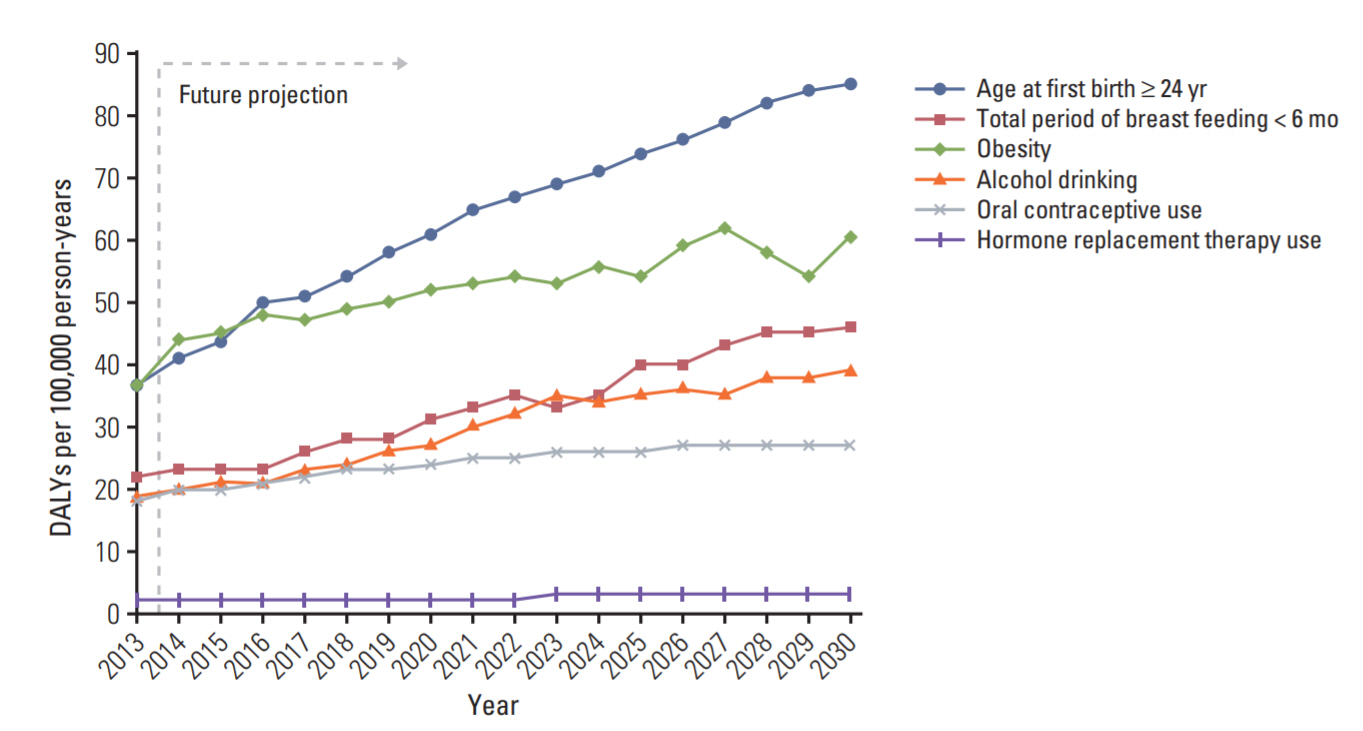

Women's reproductive/lifestyle changes, including advanced maternal age at first childbirth (from 37 to 85 disability-adjusted life years [DALYs] per 100,000 person-years), total period of breastfeeding (from 22 to 46 DALYs per 100,000 person-years), obesity (from 37 to 61 DALYs per 100,000 person-years), alcohol consumption (from 19 to 39 DALYs per 100,000 person-years), oral contraceptive use (from 18 to 27 DALYs per 100,000 person-years), and hormone replacement therapy use (from 2 to 3 DALYs per 100,000 person-years) were identified as factors likely to increase the burden of breast cancer from 2013 to 2030. Approximately, 34.2% to 44.3% of the burden of breast cancer could be avoidable in 2030 with reduction in reproductive/lifestyle risk factors.

CONCLUSION

The rapid changes of age structure and lifestyle in South Korea during the last decade are expected to strongly increase the breast cancer burden over time unless the risk factors can be effectively modified.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Oh CM, Won YJ, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Cho H, Lee JK, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2013. Cancer Res Treat. 2016; 48:436–50.

Article2. National Cancer Information Center. Survival rates of all cancers. Goyang: National Cancer Center;2016.3. Park SK, Kim Y, Kang D, Jung EJ, Yoo KY. Risk factors and control strategies for the rapidly rising rate of breast cancer in Korea. J Breast Cancer. 2011; 14:79–87.

Article4. Kontis V, Bennett JE, Mathers CD, Li G, Foreman K, Ezzati M. Future life expectancy in 35 industrialised countries: projections with a Bayesian model ensemble. Lancet. 2017; 389:1323–35.

Article5. Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014; 74:2913–21.

Article6. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997; 349:1498–504.

Article7. World Health Organization. World Health Organization global burden of disease. Geneva: World Health Organization;2007.8. Jung KW, Won YJ, Oh CM, Kong HJ, Lee DH, Lee KH. Prediction of cancer incidence and mortality in Korea, 2017. Cancer Res Treat. 2017; 49:306–12.

Article9. Jang SI, Nam JM, Choi J, Park EC. Disease management index of potential years of life lost as a tool for setting priorities in national disease control using OECD health data. Health Policy. 2014; 115:92–9.

Article10. Kunnavil R, Thirthahalli C, Nooyi SC, Somanna SN, Murthy NS. Estimation of burden of female breast cancer in India for the year 2016, 2021 and 2026 using disability adjusted life years. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2016; 3:1135–40.11. Asadzadeh Vostakolaei F, Broeders MJ, Mousavi SM, Kiemeney LA, Verbeek AL. The effect of demographic and lifestyle changes on the burden of breast cancer in Iranian women: a projection to 2030. Breast. 2013; 22:277–81.12. Harvie M, Howell A, Evans DG. Can diet and lifestyle prevent breast cancer: what is the evidence? Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2015; e66–e73.

Article13. Park B, Park S, Shin HR, Shin A, Yeo Y, Choi JY, et al. Population attributable risks of modifiable reproductive factors for breast and ovarian cancers in Korea. BMC Cancer. 2016; 16:5.

Article14. Hayes J, Richardson A, Frampton C. Population attributable risks for modifiable lifestyle factors and breast cancer in New Zealand women. Intern Med J. 2013; 43:1198–204.

Article15. Moller B, Fekjaer H, Hakulinen T, Sigvaldason H, Storm HH, Talback M, et al. Prediction of cancer incidence in the Nordic countries: empirical comparison of different approaches. Stat Med. 2003; 22:2751–66.16. Kruijshaar ME, Barendregt JJ, Van De Poll-Franse LV. Estimating the prevalence of breast cancer using a disease model: data problems and trends. Popul Health Metr. 2003; 1:5.

Article17. Barendregt JJ, Van Oortmarssen GJ, Vos T, Murray CJ. A generic model for the assessment of disease epidemiology: the computational basis of DisMod II. Popul Health Metr. 2003; 1:4.

Article18. World Health Organization. The global burden of disease concept. Geneva: World Health Organization;2016.19. Hanley JA. A heuristic approach to the formulas for population attributable fraction. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001; 55:508–14.

Article20. Statistics Korea. Korean statistical information service: population (estimated population, life table), welfare (causes of death, cancer registry). Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2015.21. National Cancer Institute. Cancer statistics. Goyang: National Cancer Center;2013.22. Park E, Park J. The analysis and reduction strategies of cancer burden in Korea. Seoul: Korean Foundation for Cancer Research;2012.23. Barendregt JJ, Van Oortmarssen GJ, Vos T, Murray CJ. A generic model for the assessment of disease epidemiology: the computational basis of DisMod II. Popul Health Metr. 2003; 1:4.

Article24. Park SH. Estimation of population attributable fraction for cancer risk factors and prediction of cancer incidence and mortality rates in Korea. Goyang: National Cancer Center;2009.25. Statistics Korea. Social survey [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2015. [cited 2017 Jul 21]. Available from: http://kostat.go.kr/.26. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001-2015 [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2017. [cited 2017 Jul 21]. Available from: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/eng/index.do/.27. Park IH, Hwang NM. The analysis of breast feeding status and breast feeding supporting policy. Sejong: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;1994.28. Microdata Integrated Service. Birth data 1998-2015. [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2015. [cited 2017 Jul 21]. Available from: https://mdis.kostat.go.kr/.29. Li L, Ji J, Wang JB, Niyazi M, Qiao YL, Boffetta P. Attributable causes of breast cancer and ovarian cancer in china: reproductive factors, oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy. Chin J Cancer Res. 2012; 24:9–17.

Article30. Park JH, Lee KS, Choi KS. Burden of cancer in Korea during 2000-2020. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013; 37:353–9.

Article31. Statistics Korea. Total fertility rate [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2016. [cited 2017 Jul 21]. Available from: https://mdis.kostat.go.kr/.32. Ma L. Female labour force participation and second birth rates in South Korea. J Popul Res. 2016; 33:173–95.

Article33. Statistics Korea. Birth statistics [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2016. [cited 2017 Jul 21]. Available from: https://mdis.kostat.go.kr/.34. Lim JW. The changing trends in live birth statistics in Korea, 1970 to 2010. Korean J Pediatr. 2011; 54:429–35.

Article35. Kim MH. The trend of international population aging. Vol. 2. Seoul: Korea Insurance Research Institute;2016. p. 21–3.36. Dowsett M, Folkerd E. Reduced progesterone levels explain the reduced risk of breast cancer in obese premenopausal women: a new hypothesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015; 149:1–4.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Risk Factors of Female Breast Cancer in Vietnam: A Case-Control Study

- Trends in incidence of uterine cancer in Songkhla, Southern Thailand

- Risk Factors for Breast Cancer: A Case-Control Study

- Age-Period-Cohort Analysis of Female Breast Cancer Mortality in Korea

- Projection of the Years of Life Lost, Years Lived with Disability, and ​Disability-Adjusted Life Years in Korea for 2030