Korean Circ J.

2018 Oct;48(10):906-916. 10.4070/kcj.2017.0395.

Ergonovine Stress Echocardiography for the Diagnosis of Vasospastic Angina and Its Prognostic Implications in 3,094 Consecutive Patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea.

- 2Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Gangneung Asan Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Gangneung, Korea. bovio@naver.com

- KMID: 2420642

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2017.0395

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

Ergonovine stress echocardiography (ErgECHO) has been proposed as a noninvasive tool for the diagnosis of coronary vasospasm. However, concern over the safety of ErgECHO remains. This study was undertaken to investigate the safety and prognostic value of ErgECHO in a large population.

METHODS

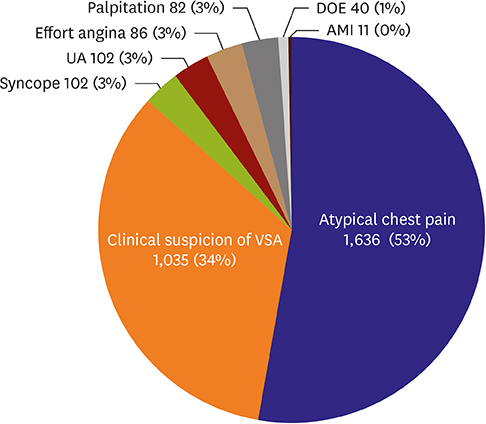

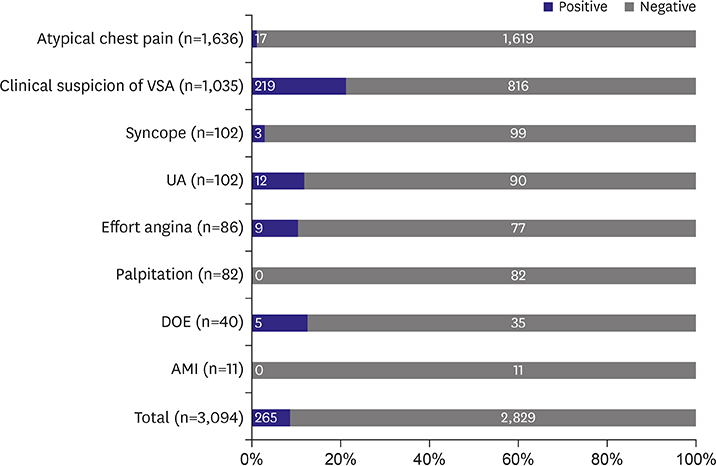

We studied 3,094 consecutive patients from a single-center registry who underwent ErgECHO from November 2002 to June 2009. Medical records, echocardiographic data, and laboratory findings obtained from follow-up periods were analyzed.

RESULTS

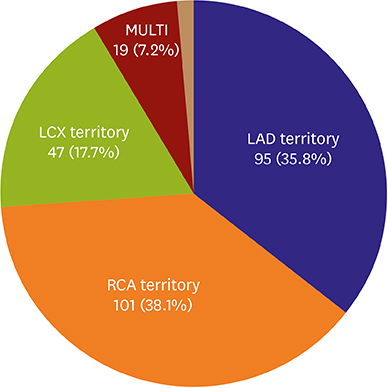

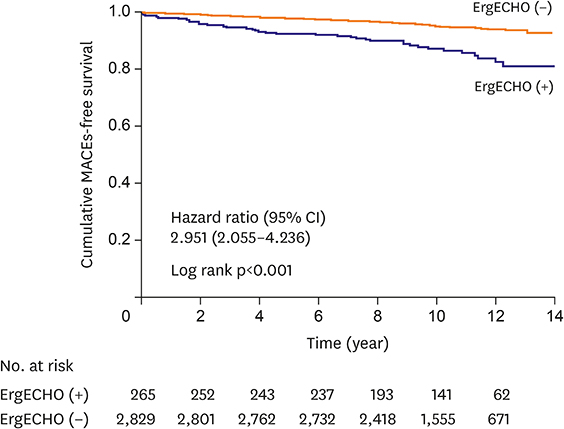

The overall positive rate of ErgECHO was 8.6%. No procedure-related mortality or myocardial infarction (MI) occurred. Nineteen patients (0.6%) had transient symptomatic complications during ErgECHO including one who was successfully resuscitated. Cumulative major adverse cardiac events (MACEs) occurred in 14.0% and 5.1% of the patients with positive and negative ErgECHO results, respectively (p < 0.001) at a median follow-up of 10.5 years. Cox regression survival analyses revealed that male sex, age, presence of diabetes, total cholesterol level of >220 mg/dL, and positive ErgECHO result itself were independent factors associated with MACEs.

CONCLUSIONS

ErgECHO can be performed safely by experienced physicians and its positive result may be an independent risk factor for long-term adverse outcomes. It may also be an alternative tool to invasive ergonovine-provoked coronary angiography for the diagnosis of vasospastic angina.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Ergonovine Provocation Echocardiography for Detection and Prognostication in Patients with Vasospastic Angina

Jae-Hyeong Park

Korean Circ J. 2018;48(10):917-919. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2018.0139.

Reference

-

1. Yasue H, Nakagawa H, Itoh T, Harada E, Mizuno Y. Coronary artery spasm--clinical features, diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. J Cardiol. 2008; 51:2–17.

Article2. JCS Joint Working Group. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of patients with vasospastic angina (Coronary Spastic Angina) (JCS 2013). Circ J. 2014; 78:2779–2801.3. Cortell A, Marcos-Alberca P, Almería C, et al. Ergonovine stress echocardiography: recent experience and safety in our centre. World J Cardiol. 2010; 2:437–442.

Article4. Morales MA, Lombardi M, Distante A, Carpeggiani C, Reisenhofer B, L'Abbate A. Ergonovine-echo test to assess the significance of chest pain at rest without ECG changes. Eur Heart J. 1995; 16:1361–1366.

Article5. Song JK, Lee SJ, Kang DH, et al. Ergonovine echocardiography as a screening test for diagnosis of vasospastic angina before coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996; 27:1156–1161.

Article6. Song JK, Park SW, Kang DH, et al. Safety and clinical impact of ergonovine stress echocardiography for diagnosis of coronary vasospasm. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 35:1850–1856.

Article7. Pepine CJ. Ergonovine echocardiography for coronary spasm: facts and wishful thinking. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996; 27:1162–1163.

Article8. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50:e1–157.9. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Glob Heart. 2012; 7:275–295.

Article10. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent st-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:267–315.11. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015; 28:1–39.e14.

Article12. Kim MH, Park EH, Yang DK, et al. Role of vasospasm in acute coronary syndrome: insights from ergonovine stress echocardiography. Circ J. 2005; 69:39–43.13. Lattanzi F, Picano E, Adamo E, Varga A. Dobutamine stress echocardiography: safety in diagnosing coronary artery disease. Drug Saf. 2000; 22:251–262.14. Previtali M, Klersy C, Salerno JA, et al. Ventricular tachyarrhythmias in Prinzmetal's variant angina: clinical significance and relation to the degree and time course of S-T segment elevation. Am J Cardiol. 1983; 52:19–25.

Article15. Distante A, Rovai D, Picano E, et al. Transient changes in left ventricular mechanics during attacks of Prinzmetal's angina: an M-mode echocardiographic study. Am Heart J. 1984; 107:465–474.

Article16. Nesto RW, Kowalchuk GJ. The ischemic cascade: temporal sequence of hemodynamic, electrocardiographic and symptomatic expressions of ischemia. Am J Cardiol. 1987; 59:23C–30C.

Article17. Rovai D, Distante A, Moscarelli E, et al. Transient myocardial ischemia with minimal electrocardiographic changes: an echocardiographic study in patients with Prinzmetal's angina. Am Heart J. 1985; 109:78–83.

Article18. Song JK, Park SW, Kang DH, et al. Prognostic implication of ergonovine echocardiography in patients with near normal coronary angiogram or negative stress test for significant fixed stenosis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002; 15:1346–1352.

Article19. Song JK, Park SW, Kang DH, et al. Diagnosis of coronary vasospasm in patients with clinical presentation of unstable angina pectoris using ergonovine echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1998; 82:1475–1478.

Article20. Shimada T, Ishibashi Y, Murakami Y, et al. Myocardial ischemia due to vasospasm of small coronary arteries detected by methylergometrine maleate stress myocardial scintigraphy. Clin Cardiol. 1999; 22:795–802.

Article21. Zaya M, Mehta PK, Merz CN. Provocative testing for coronary reactivity and spasm. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63:103–109.22. Ong P, Athanasiadis A, Borgulya G, Mahrholdt H, Kaski JC, Sechtem U. High prevalence of a pathological response to acetylcholine testing in patients with stable angina pectoris and unobstructed coronary arteries. The ACOVA study (Abnormal COronary VAsomotion in patients with stable angina and unobstructed coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 59:655–662.23. Kishida H, Tada Y, Fukuma N, Saitoh T, Kusama Y, Sano J. Significant characteristics of variant angina patients with associated syncope. Jpn Heart J. 1996; 37:317–326.

Article24. Douglas PS, Patel MR, Bailey SR, et al. Hospital variability in the rate of finding obstructive coronary artery disease at elective, diagnostic coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:801–809.

Article25. Takagi Y, Yasuda S, Takahashi J, et al. Clinical implications of provocation tests for coronary artery spasm: safety, arrhythmic complications, and prognostic impact: multicentre registry study of the Japanese Coronary Spasm Association. Eur Heart J. 2013; 34:258–267.

Article26. Takagi Y, Takahashi J, Yasuda S, et al. Prognostic stratification of patients with vasospastic angina: a comprehensive clinical risk score developed by the Japanese Coronary Spasm Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62:1144–1153.27. Sato K, Kaikita K, Nakayama N, et al. Coronary vasomotor response to intracoronary acetylcholine injection, clinical features, and long-term prognosis in 873 consecutive patients with coronary spasm: analysis of a single-center study over 20 years. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013; 2:e000227.

Article28. Takagi Y, Yasuda S, Tsunoda R, et al. Clinical characteristics and long-term prognosis of vasospastic angina patients who survived out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: multicenter registry study of the Japanese Coronary Spasm Association. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011; 4:295–302.29. Yamagishi M, Ito K, Tsutsui H, et al. Lesion severity and hypercholesterolemia determine long-term prognosis of vasospastic angina treated with calcium channel antagonists. Circ J. 2003; 67:1029–1035.

Article30. Yasue H, Takizawa A, Nagao M, et al. Long-term prognosis for patients with variant angina and influential factors. Circulation. 1988; 78:1–9.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Ergonovine Echocardiography for the Diagnosis of Vasospastic Angina

- Exercise-Induced Vasospastic Angina With Prominent Regional Wall Motion Abnormality

- Ergonovine Provocation Echocardiography for Detection and Prognostication in Patients with Vasospastic Angina

- Diagnostic Significance of ECG Ergonovine Provocation Test in Patients with Vasospastic Angina

- A Case of Cardiac Arrest during Ergonovine Stress Echocardiography