Obstet Gynecol Sci.

2017 Nov;60(6):499-505. 10.5468/ogs.2017.60.6.499.

Vacuum extraction vaginal delivery: current trend and safety

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kangwon National University Hospital, School of Medicine Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, Korea. lahun@kangwon.ac.kr

- KMID: 2418350

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2017.60.6.499

Abstract

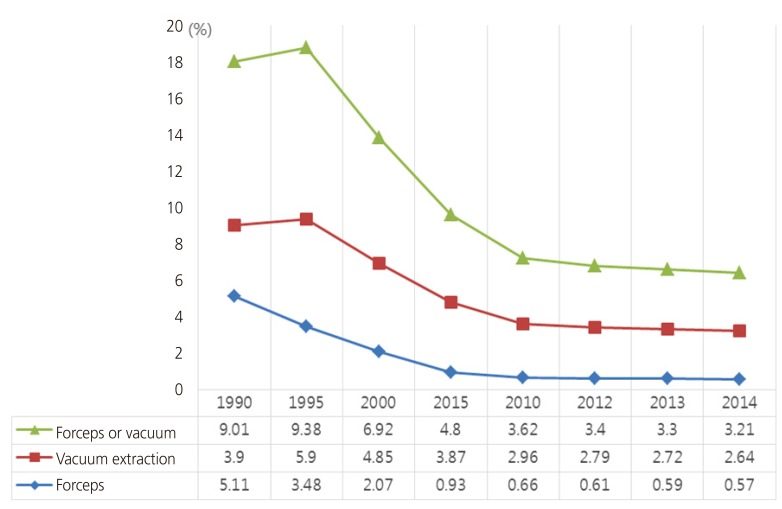

- Operative vaginal birth retains an important role in current obstetric practice. However, there is an increasing trend in the rate of cesarean section in Korea. Surgical delivery is more advantageous than cesarean section, but the rate of operative vaginal delivery is decreasing for various reasons. Furthermore, there is no unified technique for vacuum extraction delivery. In this context, this review was performed to provide details of the necessary conditions, techniques, benefits, and risks of operative vaginal delivery. Future research should focus on overcoming the limitations of operative vaginal delivery.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Can the cervical length in mid-trimester predict the use of vacuum in vaginal delivery?

Jee Yoon Park, Sun Min Kim, Jeenah Sohn, Sejin Kim, Eunjin Song, Byoung Jae Kim, Hye Won Jeon

Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2020;63(1):35-41. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2020.63.1.35.

Reference

-

1. Statistics Korea. Data of statistics Korea [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2017. cited 2017 May 30. Available from: http://kostat.go.kr.2. Korean Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Obstetrics. 4th ed. Seoul: Koonja;2007.3. Spong CY, Berghella V, Wenstrom KD, Mercer BM, Saade GR. Preventing the first cesarean delivery: summary of a joint Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 120:1181–1193. PMID: 23090537.4. Murphy DJ, Liebling RE, Verity L, Swingler R, Patel R. Early maternal and neonatal morbidity associated with operative delivery in second stage of labour: a cohort study. Lancet. 2001; 358:1203–1207. PMID: 11675055.

Article5. Contag SA, Clifton RG, Bloom SL, Spong CY, Varner MW, Rouse DJ, et al. Neonatal outcomes and operative vaginal delivery versus cesarean delivery. Am J Perinatol. 2010; 27:493–499. PMID: 20099218.

Article6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric care consensus no. 1: safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 123:693–711. PMID: 24553167.7. Deneux-Tharaux C, Carmona E, Bouvier-Colle MH, Bréart G. Postpartum maternal mortality and cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 108:541–548. PMID: 16946213.

Article8. Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Thom EA, et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 107:1226–1232. PMID: 16738145.

Article9. Cheong YC, Abdullahi H, Lashen H, Fairlie FM. Can formal education and training improve the outcome of instrumental delivery? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004; 113:139–144. PMID: 15063949.

Article10. Wen SW, Liu S, Kramer MS, Marcoux S, Ohlsson A, Sauvé R, et al. Comparison of maternal and infant outcomes between VE and forceps deliveries. Am J Epidemiol. 2001; 153:103–107. PMID: 11159152.11. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Instrumental vaginal birth. East Melbourne: The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists;2016.12. Gupta JK, Hofmeyr GJ, Shehmar M. Position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; CD002006. PMID: 22592681.

Article13. Anim-Somuah M, Smyth R, Howell C. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005; CD000331. PMID: 16235275.

Article14. Roberts CL, Torvaldsen S, Cameron CA, Olive E. Delayed versus early pushing in women with epidural analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2004; 111:1333–1340. PMID: 15663115.

Article15. Weiss JL, Malone FD, Emig D, Ball RH, Nyberg DA, Comstock CH, et al. Obesity, obstetric complications and cesarean delivery rate--a population-based screening study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 190:1091–1097. PMID: 15118648.

Article16. NIH Consensus Statement on Management of Hepatitis C. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2002; 19:1–46.17. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Delivery by vacuum extraction. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 208. Washington, D.C.: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists;1998.18. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Operative vaginal delivery. Practice bulletin no. 17. Washington, D.C.: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists;2000.19. O'Mahony F, Hofmeyr GJ, Menon V. Choice of instruments for assisted vaginal delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; CD005455. PMID: 21069686.20. Suwannachat B, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M. Rapid versus stepwise negative pressure application for vacuum extraction assisted vaginal delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; CD006636. PMID: 22895953.

Article21. Le Ray C, Deneux-Tharaux C, Khireddine I, Dreyfus M, Vardon D, Goffinet F. Manual rotation to decrease operative delivery in posterior or transverse positions. Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 122:634–640. PMID: 23921875.

Article22. Pearl ML, Roberts JM, Laros RK, Hurd WW. Vaginal delivery from the persistent occiput posterior position. Influence on maternal and neonatal morbidity. J Reprod Med. 1993; 38:955–961. PMID: 8120853.23. Ecker JL, Tan WM, Bansal RK, Bishop JT, Kilpatrick SJ. Is there a benefit to episiotomy at operative vaginal delivery? Observations over ten years in a stable population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997; 176:411–414. PMID: 9065190.

Article24. Hirayama F, Koyanagi A, Mori R, Zhang J, Souza JP, Gülmezoglu AM. Prevalence and risk factors for third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations during vaginal delivery: a multi-country study. BJOG. 2012; 119:340–347. PMID: 22239415.

Article25. Murphy DJ, Macleod M, Bahl R, Goyder K, Howarth L, Strachan B. A randomised controlled trial of routine versus restrictive use of episiotomy at operative vaginal delivery: a multicentre pilot study. BJOG. 2008; 115:1695–1702. PMID: 19035944.

Article26. de Vogel J, van der Leeuw-van Beek A, Gietelink D, Vujkovic M, de Leeuw JW, van Bavel J, et al. The effect of a mediolateral episiotomy during operative vaginal delivery on the risk of developing obstetrical anal sphincter injuries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 206:404.e1–404.e5. PMID: 22425401.

Article27. de Leeuw JW, de Wit C, Kuijken JP, Bruinse HW. Mediolateral episiotomy reduces the risk for anal sphincter injury during operative vaginal delivery. BJOG. 2008; 115:104–108. PMID: 17999693.

Article28. Baskett TF, Fanning CA, Young DC. A prospective observational study of 1000 vacuum assisted deliveries with the OmniCup device. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008; 30:573–580. PMID: 18644178.

Article29. Bofill JA, Rust OA, Schorr SJ, Brown RC, Roberts WE, Morrison JC. A randomized trial of two vacuum extraction techniques. Obstet Gynecol. 1997; 89:758–762. PMID: 9166316.

Article30. Vacca A. The trouble with vacuum extraction. Curr Obstet Gynaecol. 1999; 9:41–45.

Article31. Towner D, Castro MA, Eby-Wilkens E, Gilbert WM. Effect of mode of delivery in nulliparous women on neonatal intracranial injury. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341:1709–1714. PMID: 10580069.

Article32. Gurol-Urganci I, Cromwell DA, Edozien LC, Mahmood TA, Adams EJ, Richmond DH, et al. Third- and fourth-degree perineal tears among primiparous women in England between 2000 and 2012: time trends and risk factors. BJOG. 2013; 120:1516–1525. PMID: 23834484.

Article33. Kudish B, Blackwell S, Mcneeley SG, Bujold E, Kruger M, Hendrix SL, et al. Operative vaginal delivery and midline episiotomy: a bad combination for the perineum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 195:749–754. PMID: 16949408.

Article34. Handa VL, Blomquist JL, McDermott KC, Friedman S, Muñoz A. Pelvic floor disorders after vaginal birth: effect of episiotomy, perineal laceration, and operative birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 119:233–239. PMID: 22227639.35. Baud D, Meyer S, Vial Y, Hohlfeld P, Achtari C. Pelvic floor dysfunction 6 years post-anal sphincter tear at the time of vaginal delivery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2011; 22:1127–1134.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Study Female of Fecal Incontinence: Effects of Parity & Delivery method

- A Floppy Baby with Congenital Myotonic Dystrophy Complicated with Huge Subgaleal Hematoma Occurring in Non-instrumental Vaginal Delivery

- Effect of Labor Epidural Analgesia on Rates of Cesarean Section and Vacuum Delivery

- Can the cervical length in mid-trimester predict the use of vacuum in vaginal delivery?

- Comparison of neonatal outcomes and intrapartum events in full term vaginal deliveries conducted by staff versus resident physicians