J Gynecol Oncol.

2017 Nov;28(6):e75. 10.3802/jgo.2017.28.e75.

Down-regulated serum microRNA-101 is associated with aggressive progression and poor prognosis of cervical cancer

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Jiangxi Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Nanchang, China. jacky5824@163.com

- 2Department of Reproduction, Jiangxi Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Nanchang, China.

- 3Department of Pathology, Jiangxi Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Nanchang, China.

- 4School of Life Science, Jiangxi Science & Technology Normal University, Nanchang, China. yaolh79@yahoo.com

- KMID: 2413201

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2017.28.e75

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) play a vital role in pathogenesis and progression of many cancers, including cervical cancer. However, importance of serum level of miR-101 in cervical cancer has rarely been studied. In the present study, clinical significance and prognostic value of serum miR-101 for cervical cancer was investigated.

METHODS

Association between miR-101 level in cervical cancer tissues and prognosis of patients was analyzed by using data retrieved from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database, which was followed with our clinical study in which miR-101 serum level comparison between cervical cancer patients and healthy controls was conducted by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

RESULTS

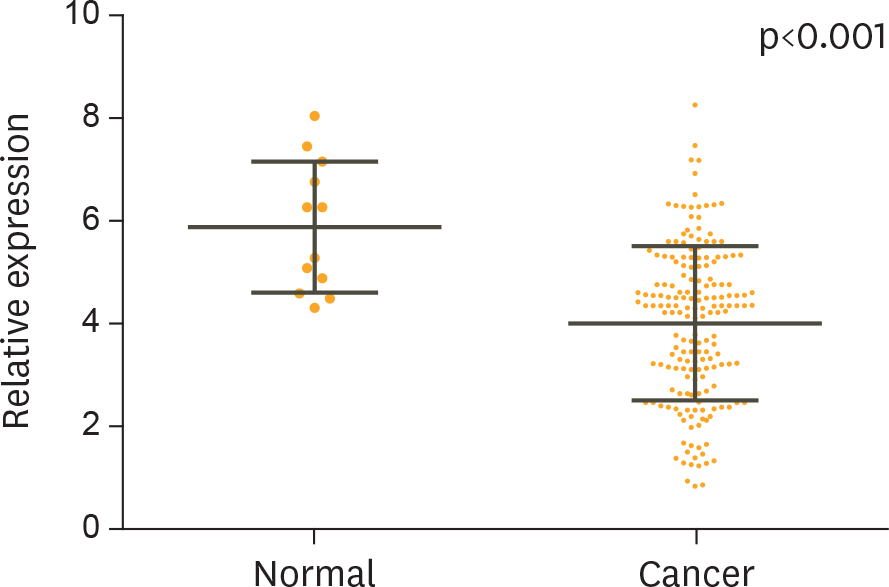

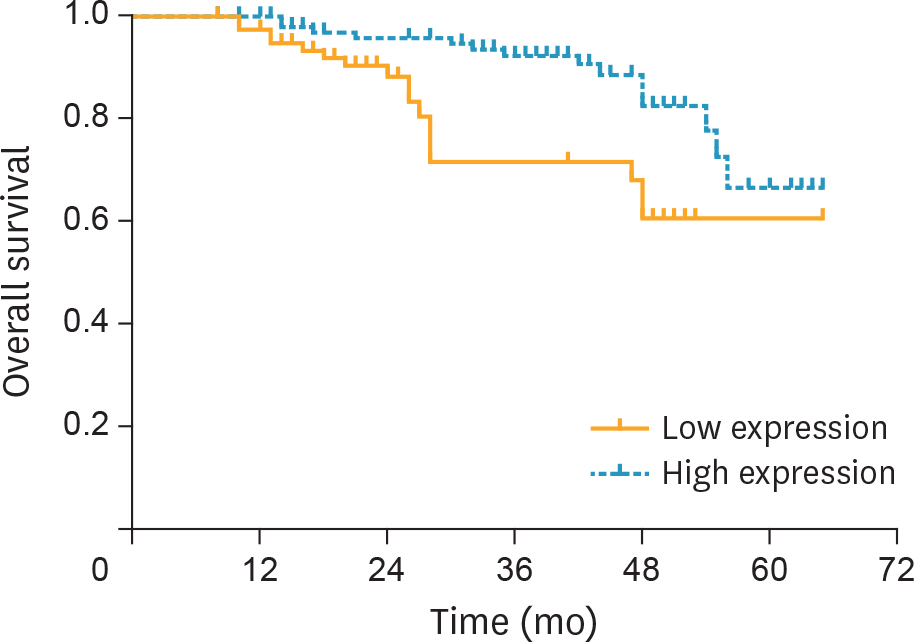

TCGA database demonstrated that miR-101 was down-regulated in cervical cancer tissues compared with normal cervical tissues, and univariate Cox regression analysis indicated that decreased miR-101 expression was a highly significant negative risk factor. Similar trend was found in the serum miR-101. Serum level of miR-101 was associated with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage (p=0.003), lymph node metastasis (p=0.001), and serum squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC-Ag) level >4 (p=0.007). The overall survival time of cervical cancer patients with a higher level of serum miR-101 was significantly longer than that of patients with a lower level of serum miR-101. Moreover, multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated that the down-regulated serum level of miR-101 was an independent predictor for the unfavorable prognosis of cervical cancer.

CONCLUSION

Serum level of miR-101 is closely associated with metastasis and prognosis of cervical cancer; and, hence could be a potential biomarker and prognostic predictor for cervical cancer.

MeSH Terms

-

Antigens, Neoplasm/blood

Case-Control Studies

Disease Progression

Down-Regulation

Female

Humans

Lymphatic Metastasis

MicroRNAs/*metabolism

Middle Aged

Multivariate Analysis

Neoplasm Staging

Prognosis

Proportional Hazards Models

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction

Serpins/blood

Uterine Cervical Neoplasms/*metabolism/pathology

Antigens, Neoplasm

MicroRNAs

Serpins

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015; 65:87–108.

Article2. Vaccarella S, Lortet-Tieulent J, Plummer M, Franceschi S, Bray F. Worldwide trends in cervical cancer incidence: impact of screening against changes in disease risk factors. Eur J Cancer. 2013; 49:3262–73.

Article3. Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004; 431:350–5.

Article4. Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs – microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006; 6:259–69.

Article5. Weiland M, Gao XH, Zhou L, Mi QS. Small RNAs have a large impact: circulating microRNAs as biomarkers for human diseases. RNA Biol. 2012; 9:850–9.6. Nugent M, Miller N, Kerin MJ. Circulating miR-34a levels are reduced in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2012;106:947–52.

Article7. Schetter AJ, Okayama H, Harris CC. The role of microRNAs in colorectal cancer. Cancer J. 2012; 18:244–52.

Article8. Lim LP, Glasner ME, Yekta S, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Vertebrate microRNA genes. Science. 2003; 299:1540.

Article9. Silahtaroglu A, Stenvang J. MicroRNAs, epigenetics and disease. Essays Biochem. 2010; 48:165–85.

Article10. Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Liu CG, Veronese A, Spizzo R, Sabbioni S, et al. MicroRNA gene expression deregulation in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005; 65:7065–70.

Article11. Liu L, Guo J, Yu L, Cai J, Gui T, Tang H, et al. miR-101 regulates expression of EZH2 and contributes to progression of and cisplatin resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014; 35:12619–26.

Article12. Yanaihara N, Caplen N, Bowman E, Seike M, Kumamoto K, Yi M, et al. Unique microRNA molecular profiles in lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Cell. 2006; 9:189–98.

Article13. Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:e47.

Article14. Chan JA, Krichevsky AM, Kosik KS. MicroRNA-21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005; 65:6029–33.

Article15. Tian Y, Luo A, Cai Y, Su Q, Ding F, Chen H, et al. MicroRNA-10b promotes migration and invasion through KLF4 in human esophageal cancer cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2010; 285:7986–94.

Article16. Calin GA, Cimmino A, Fabbri M, Ferracin M, Wojcik SE, Shimizu M, et al. MiR-15a and miR-16-1 cluster functions in human leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008; 105:5166–71.

Article17. Park SY, Lee JH, Ha M, Nam JW, Kim VN. miR-29 miRNAs activate p53 by targeting p85 alpha and CDC42. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009; 16:23–9.18. Yang Z, Chen S, Luan X, Li Y, Liu M, Li X, et al. MicroRNA-214 is aberrantly expressed in cervical cancers and inhibits the growth of HeLa cells. IUBMB Life. 2009; 61:1075–82.

Article19. Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, Cai X, Yin Y, Wang K, et al. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res. 2008; 18:997–1006.

Article20. Piao J, You K, Guo Y, Zhang Y, Li Z, Geng L. Substrate stiffness affects epithelial-mesenchymal transition of cervical cancer cells through miR-106b and its target protein DAB2. Int J Oncol. 2017; 50:2033–42.

Article21. Wang C, Zhou B, Liu M, Liu Y, Gao R. miR-126-5p restoration promotes cell apoptosis in cervical cancer by targeting Bcl2l2. Oncol Res. 2017; 25:463–70.

Article22. Guo M, Zhao X, Yuan X, Jiang J, Li P. MiR-let-7a inhibits cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by down-regulating PKM2 in cervical cancer. Oncotarget. 2017; 8:28226–36.

Article23. Liu Z, Wang J, Mao Y, Zou B, Fan X. MicroRNA-101 suppresses migration and invasion via targeting vascular endothelial growth factor-C in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol Lett. 2016; 11:433–8.

Article24. Liang X, Liu Y, Zeng L, Yu C, Hu Z, Zhou Q, et al. miR-101 inhibits the G1-to-S phase transition of cervical cancer cells by targeting Fos. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014; 24:1165–72.25. Lin C, Huang F, Shen G, Yiming A. MicroRNA-101 regulates the viability and invasion of cervical cancer cells. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015; 8:10148–55.26. Oh J, Lee HJ, Lee TS, Kim JH, Koh SB, Choi YS. Clinical value of routine serum squamous cell carcinoma antigen in follow-up of patients with locally advanced cervical cancer treated with radiation or chemoradiation. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2016; 59:269–78.

Article27. Esajas MD, Duk JM, de Bruijn HW, Aalders JG, Willemse PH, Sluiter W, et al. Clinical value of routine serum squamous cell carcinoma antigen in follow-up of patients with early-stage cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001; 19:3960–6.

Article28. Li J, Chen P, Mao CM, Tang XP, Zhu LR. Evaluation of diagnostic value of four tumor markers in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of peripheral lung cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014; 10:141–8.

Article29. Cao X, Zhang L, Feng GR, Yang J, Wang RY, Li J, et al. Preoperative Cyfra21-1 and SCC-Ag serum titers predict survival in patients with stage II esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2012; 10:197.

Article30. Torre GC. SCC antigen in malignant and nonmalignant squamous lesions. Tumour Biol. 1998; 19:517–26.

Article31. Ryu HK, Baek JS, Kang WD, Kim SM. The prognostic value of squamous cell carcinoma antigen for predicting tumor recurrence in cervical squamous cell carcinoma patients. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2015; 58:368–76.

Article32. Manetta A, Delgado G, Petrilli E, Hummel S, Barnes W. The significance of paraaortic node status in carcinoma of the cervix and endometrium. Gynecol Oncol. 1986; 23:284–90.

Article33. Yoon HI, Cha J, Keum KC, Lee HY, Nam EJ, Kim SW, et al. Treatment outcomes of extended-field radiation therapy and the effect of concurrent chemotherapy on uterine cervical cancer with paraaortic lymph node metastasis. Radiat Oncol. 2015; 10:18.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Paip1 Indicated Poor Prognosis in Cervical Cancer and Promoted Cervical Carcinogenesis

- High MicroRNA-370 Expression Correlates with Tumor Progression and Poor Prognosis in Breast Cancer

- Quantitative Measurement of Serum MicroRNA-21 Expression in Relation to Breast Cancer Metastasis in Chinese Females

- The Role of MicroRNA in Head and Neck Cancer

- Surveillance and Early Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cancer