Anesth Pain Med.

2017 Oct;12(4):297-305. 10.17085/apm.2017.12.4.297.

Radiation exposure and protection for eyes in pain management

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Konkuk University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. painfree@kuh.ac.kr

- KMID: 2405846

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.17085/apm.2017.12.4.297

Abstract

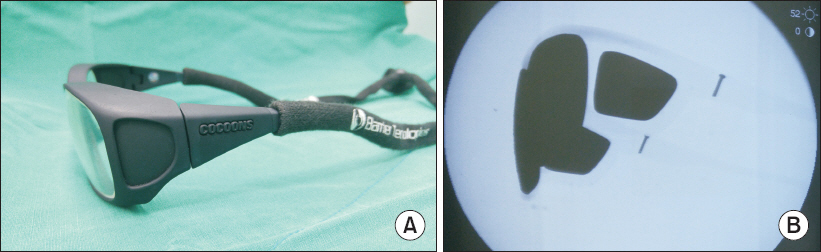

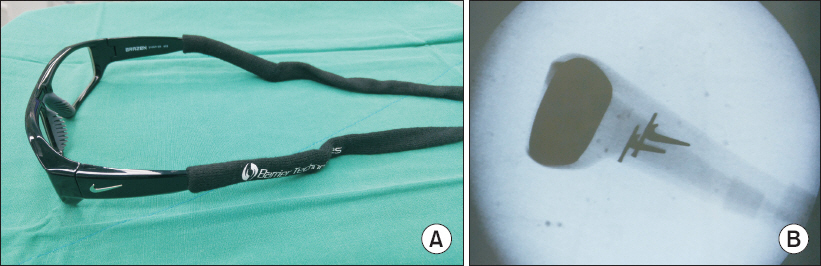

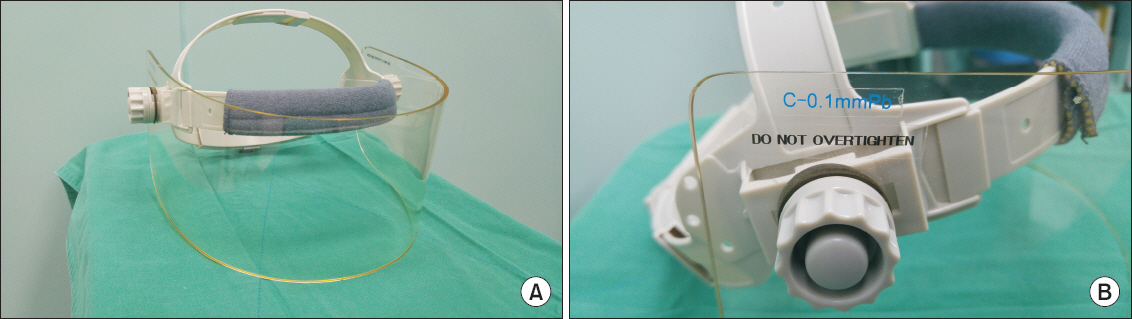

- C-arm fluoroscopy is important device for pain management. However, pain physicians can be exposed to radiation during C-arm fluoroscopy-guided interventions. In the annual maximal permissible radiation doses, the dose of lens is lower than the doses of the thyroid and gonads. In the human body, the lens of eye is one of the most sensitive parts for radiation exposure. Cataract or opacity of lens is the most common complication of eye related to radiation. Several years ago, the threshold dose of a radiation induced cataract was changed to 0.5 Gy. In 2011, International Commission on Radiological Protection reduced the annual permissible radiation dose for the lens from 150 mSv to 20 mSv. According to the lower level of permissible radiation dose for lens, physicians should reduce their radiation exposure. This review presents the complications of the lens related to radiation exposure, permissible doses for the lens, radiation exposure of physicians, protective devices for the lens, and methods for radiation safety.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Radiation safety for pain physicians: principles and recommendations

Sewon Park, Minjung Kim, Jae Hun Kim

Korean J Pain. 2022;35(2):129-139. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2022.35.2.129.

Reference

-

1. Jeong JS, Shim JC, Woo JP, Shim JH, Kim DW, Kim KS. Epidural contrast flow patterns of retrograde interlaminar ventral epidural injections stratified by the final catheter tip placement. Anesth Pain Med. 2013; 8:158–65.2. Kim MG, Choi DH, Kim H, Cho A, Park SY, Kim SH, et al. Prediction of midline depth from skin to cervical epidural space by lateral cervical spine X-ray. Anesth Pain Med. 2017; 12:68–71. DOI: 10.17085/apm.2017.12.1.68.3. Kim TH, Hong SW, Woo NS, Kim HK, Kim JH. The radiation safety education and the pain physicians'efforts to reduce radiation exposure. Korean J Pain. 2017; 30:104–15. DOI: 10.3344/kjp.2017.30.2.104. PMID: 28416994. PMCID: PMC5392654.4. Chang YJ, Kim AN, Oh IS, Woo NS, Kim HK, Kim JH. The radiation exposure of radiographer related to the location in c-arm fluoroscopy-guided pain interventions. Korean J Pain. 2014; 27:162–7. DOI: 10.3344/kjp.2014.27.2.162. PMID: 24748945. PMCID: PMC3990825.5. Hamada N, Fujimichi Y. Role of carcinogenesis related mechanisms in cataractogenesis and its implications for ionizing radiation cataractogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2015; 368:262–74. DOI: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.02.017. PMID: 25687882.6. Cho JH, Kim JY, Kang JE, Park PE, Kim JH, Lim JA, et al. A study to compare the radiation absorbed dose of the C-arm fluoroscopic modes. Korean J Pain. 2011; 24:199–204. DOI: 10.3344/kjp.2011.24.4.199. PMID: 22220241. PMCID: PMC3248583.7. Kim AN, Chang YJ, Cheon BK, Kim JH. How effective are radiation reducing gloves in C-arm fluoroscopy-guided pain interventions? Korean J Pain. 2014; 27:145–51. DOI: 10.3344/kjp.2014.27.2.145. PMID: 24748943. PMCID: PMC3990823.8. Stewart FA, Akleyev AV, Hauer-Jensen M, Hendry JH, Kleiman NJ, Macvittie TJ, et al. ICRP publication 118:ICRP statement on tissue reactions and early and late effects of radiation in normal tissues and organs--threshold doses for tissue reactions in a radiation protection context. Ann ICRP. 2012; 41:1–322. DOI: 10.1016/j.icrp.2012.02.001. PMID: 22925378.9. Dauer LT, Ainsbury EA, Dynlacht J, Hoel D, Klein BE, Mayer D, et al. Guidance on radiation dose limits for the lens of the eye:overview of the recommendations in NCRP Commentary No. 26. Int J Radiat Biol. 2017; 93:1015–23. DOI: 10.1080/09553002.2017.1304669. PMID: 28346025.10. Ainsbury EA, Bouffler SD, Dörr W, Graw J, Muirhead CR, Edwards AA, et al. Radiation cataractogenesis:a review of recent studies. Radiat Res. 2009; 172:1–9. DOI: 10.1667/RR1688.1. PMID: 19580502.11. Rehani MM, Vano E, Ciraj-Bjelac O, Kleiman NJ. Radiation and cataract. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2011; 147:300–4. DOI: 10.1093/rpd/ncr299. PMID: 21764807.12. Worgul BV, Kundiyev YI, Sergiyenko NM, Chumak VV, Vitte PM, Medvedovsky C, et al. Cataracts among Chernobyl clean-up workers:implications regarding permissible eye exposures. Radiat Res. 2007; 167:233–43. DOI: 10.1667/RR0298.1. PMID: 17390731.13. Klein BE, Klein R, Linton KL, Franke T. Diagnostic x-ray exposure and lens opacities:the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Public Health. 1993; 83:588–90. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.83.4.588. PMID: 8460743. PMCID: PMC1694473.14. Shore RE. Radiation and cataract risk:Impact of recent epidemiologic studies on ICRP judgments. Mutat Res. 2016; 770:231–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2016.06.006. PMID: 27919333.15. Zeiss CJ, Johnson EM, Dubielzig RR. Feline intraocular tumors may arise from transformation of lens epithelium. Vet Pathol. 2003; 40:355–62. DOI: 10.1354/vp.40-4-355. PMID: 12824506.16. Graw J. Mouse models of cataract. J Genet. 2009; 88:469–86. DOI: 10.1007/s12041-009-0066-2. PMID: 20090208.17. Jacob S, Boveda S, Bar O, Brézin A, Maccia C, Laurier D, et al. Interventional cardiologists and risk of radiation-induced cataract:results of a French multicenter observational study. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 167:1843–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.124. PMID: 22608271.18. Park PE, Park JM, Kang JE, Cho JH, Cho SJ, Kim JH, et al. Radiation safety and education in the applicants of the final test for the expert of pain medicine. Korean J Pain. 2012; 25:16–21. DOI: 10.3344/kjp.2012.25.1.16. PMID: 22259711. PMCID: PMC3259132.19. Brown NP. The lens is more sensitive to radiation than we had believed. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997; 81:257. DOI: 10.1136/bjo.81.4.257. PMID: 9215048. PMCID: PMC1722152.20. Chylack LT Jr, Peterson LE, Feiveson AH, Wear ML, Manuel FK, Tung WH, et al. NASA study of cataract in astronauts (NASCA). Report 1:Cross-sectional study of the relationship of exposure to space radiation and risk of lens opacity. Radiat Res. 2009; 172:10–20. DOI: 10.1667/RR1580.1. PMID: 19580503.21. Hsieh WA, Lin IF, Chang WP, Chen WL, Hsu YH, Chen MS. Lens opacities in young individuals long after exposure to protracted low-dose-rate gamma radiation in 60Co-contaminated buildings in Taiwan. Radiat Res. 2010; 173:197–204. DOI: 10.1667/RR1850.1. PMID: 20095852.22. Vañó E, González L, Beneytez F, Moreno F. Lens injuries induced by occupational exposure in non-optimized interventional radiology laboratories. Br J Radiol. 1998; 71:728–33. DOI: 10.1259/bjr.71.847.9771383. PMID: 9771383.23. Ciraj-Bjelac O, Rehani M, Minamoto A, Sim KH, Liew HB, Vano E. Radiation-induced eye lens changes and risk for cataract in interventional cardiology. Cardiology. 2012; 123:168–71. DOI: 10.1159/000342458. PMID: 23128776.24. Bertolini M, Benecchi G, Amici M, Piola A, Piccagli V, Giordano C, et al. Attenuation assessment of medical protective eyewear:the AVEN experience. J Radiol Prot. 2016; 36:279–89. DOI: 10.1088/0952-4746/36/2/279. PMID: 27122122.25. Rivett C, Dixon M, Matthews L, Rowles N. An assessment of the dose reduction of commerciallyavailable lead protective glasses for interventionalradiology staff. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2016; 172:443–52. DOI: 10.1093/rpd/ncv540. PMID: 26769907.26. Magee JS, Martin CJ, Sandblom V, Carter MJ, Almén A, Cederblad Å, et al. Derivation and application of dose reduction factors for protective eyewear worn in interventional radiology and cardiology. J Radiol Prot. 2014; 34:811–23. DOI: 10.1088/0952-4746/34/4/811. PMID: 25332300.27. Schueler BA. Operator shielding:how and why. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010; 13:167–71. DOI: 10.1053/j.tvir.2010.03.005. PMID: 20723831.28. van Rooijen BD, de Haan MW, Das M, Arnoldussen CW, de Graaf R, van Zwam WH, et al. Efficacy of radiation safety glasses in interventional radiology. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014; 37:1149–55. DOI: 10.1007/s00270-013-0766-0. PMID: 24185812.29. Koukorava C, Farah J, Struelens L, Clairand I, Donadille L, Vanhavere F, et al. Efficiency of radiation protection equipment in interventional radiology:a systematic Monte Carlo study of eye lens and whole body doses. J Radiol Prot. 2014; 34:509–28. DOI: 10.1088/0952-4746/34/3/509. PMID: 24938591.30. Waddell BS, Waddell WH, Godoy G, Zavatsky JM. Comparison of ocular radiation exposure utilizing three types of leaded glasses. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016; 41:E231–6. DOI: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001204. PMID: 26571167.31. McVey S, Sandison A, Sutton DG. An assessment of lead eyewear in interventional radiology. J Radiol Prot. 2013; 33:647–59. DOI: 10.1088/0952-4746/33/3/647. PMID: 23803599.32. Moore WE, Ferguson G, Rohrmann C. Physical factors determining the utility of radiation safety glasses. Med Phys. 1980; 7:8–12. DOI: 10.1118/1.594661. PMID: 7366548.33. Martin CJ. Eye lens dosimetry for fluoroscopically guided clinical procedures:practical approaches to protection and dose monitoring. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2016; 169:286–91. DOI: 10.1093/rpd/ncv431. PMID: 26454269.34. Lian Y, Xiao J, Ji X, Guan S, Ge H, Li F, et al. Protracted low-dose radiation exposure and cataract in a cohort of Chinese industry radiographers. Occup Environ Med. 2015; 72:640–7. DOI: 10.1136/oemed-2014-102772. PMID: 26163545.35. Maeder M, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Wolber T, Ammann P, Roelli H, Rohner F, et al. Impact of a lead glass screen on scatter radiation to eyes and hands in interventional cardiologists. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006; 67:18–23. DOI: 10.1002/ccd.20457. PMID: 16273590.36. Ryu JS, Baek SW, Jung CH, Cho SJ, Jung EG, Kim HK, et al. The survey about the degree of damage of radiation-protective shields in operation room. Korean J Pain. 2013; 26:142–7. DOI: 10.3344/kjp.2013.26.2.142. PMID: 23614075. PMCID: PMC3629340.37. Vano E, Gonzalez L, Fernández JM, Haskal ZJ. Eye lens exposure to radiation in interventional suites:caution is warranted. Radiology. 2008; 248:945–53. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2482071800. PMID: 18632529.38. Baek SW, Ryu JS, Jung CH, Lee JH, Kwon WK, Woo NS, et al. A randomized controlled trial about the levels of radiation exposure depends on the use of collimation c-arm fluoroscopic-guided medial branch block. Korean J Pain. 2013; 26:148–53. DOI: 10.3344/kjp.2013.26.2.148. PMID: 23614076. PMCID: PMC3629341.39. Domienik J, Bissinger A, Zmyślony M. The impact of x-ray tube configuration on the eye lens and extremity doses received by cardiologists in electrophysiology room. J Radiol Prot. 2014; 34:N73–9.40. Wang RR, Kumar AH, Tanaka P, Macario A. Occupational radiation exposure of anesthesia providers:a summaryof key learning points and resident-led radiation safety projects. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017; 21:165–71. DOI: 10.1177/1089253217692110. PMID: 28190371.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The radiation safety education and the pain physicians' efforts to reduce radiation exposure

- Radiation safety: a focus on lead aprons and thyroid shields in interventional pain management

- General Principles of Radiation Protection in Fields of Diagnostic Medical Exposure

- Radiation Exposure from a Patient Treated with I-131 during Emergency Operation: A case report

- Current status of medical radiation exposure and regulation efforts