Asia Pac Allergy.

2015 Apr;5(2):84-97. 10.5415/apallergy.2015.5.2.84.

Economic value of atopic dermatitis prevention via infant formula use in high-risk Malaysian infants

- Affiliations

-

- 1Pharmerit International, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA. mbotteman@pharmerit.com

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Pantai Hospital Kuala Lumpur, 59100 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- 3Department of Pediatrics, Ramsay Sime Darby, Subang Jaya Medical Centre, 47500 Subang Jaya, Malaysia.

- 4Nestlé Research Center, 1000 Lausanne 26, Switzerland.

- KMID: 2397055

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5415/apallergy.2015.5.2.84

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Breastfeeding is best for infants and the World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding for at least the first 6 months of life. For those who are unable to be breastfed, previous studies demonstrate that feeding high-risk infants with hydrolyzed formulas instead of cow's milk formula (CMF) may decrease the risk of atopic dermatitis (AD).

OBJECTIVE

To estimate the economic impact of feeding high-risk, not exclusively breastfed, urban Malaysian infants with partiallyhydrolyzed whey-based formula (PHF-W) instead of CMF for the first 17 weeks of life as an AD risk reduction strategy.

METHODS

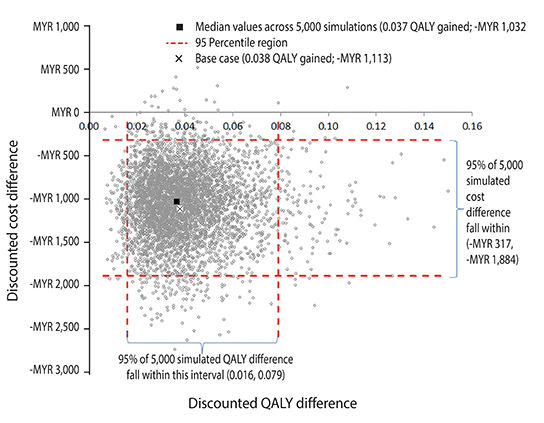

A cohort Markov model simulated the AD incidence and burden from birth to age 6 years in the target population fed with PHF-W vs. CMF. The model integrated published clinical and epidemiologic data, local cost data, and expert opinion. Modeled outcomes included AD-risk reduction, time spent post AD diagnosis, days without AD flare, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), and costs (direct and indirect). Outcomes were discounted at 3% per year. Costs are expressed in Malaysian Ringgit (MYR; MYR 1,000 = United States dollar [US $]316.50).

RESULTS

Feeding a high-risk infant PHF-W vs. CMF resulted in a 14% point reduction in AD risk (95% confidence interval [CI], 3%-23%), a 0.69-year (95% CI, 0.25-1.10) reduction in time spent post-AD diagnosis, additional 38 (95% CI, 2-94) days without AD flare, and an undiscounted gain of 0.041 (95% CI, 0.007-0.103) QALYs. The discounted AD-related 6-year cost estimates when feeding a high-risk infant with PHF-W were MYR 1,758 (US $556) (95% CI, MYR 917-3,033) and with CMF MYR 2,871 (US $909) (95% CI, MYR 1,697-4,278), resulting in a per-child net saving of MYR 1,113 (US $352) (95% CI, MYR 317-1,884) favoring PHF-W.

CONCLUSION

Using PHF-W instead of CMF in this population is expected to result in AD-related costs savings.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

In this issue of Asia Pacific allergy

Constance H. Katelaris

Asia Pac Allergy. 2015;5(2):57-58. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2015.5.2.57.

Reference

-

1. Spergel JM, Paller AS. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003; 112:6 Suppl. S118–S127.

Article2. Catherine Mack Correa M, Nebus J. Management of patients with atopic dermatitis: the role of emollient therapy. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012; 2012:836931.3. Lewis-Jones S. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract. 2006; 60:984–992.

Article4. Asher MI, Montefort S, Bjorksten B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, Williams H. ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006; 368:733–743.

Article5. Aziah MS, Rosnah T, Mardziah A, Norzila MZ. Childhood atopic dermatitis: a measurement of quality of life and family impact. Med J Malaysia. 2002; 57:329–339.6. Su JC, Kemp AS, Varigos GA, Nolan TM. Atopic eczema: its impact on the family and financial cost. Arch Dis Child. 1997; 76:159–162.

Article7. Williams H, Stewart A, von Mutius E, Cookson W, Anderson HR. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase One and Three Study Groups. Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008; 121:947–954.e15.

Article8. Ngamphaiboon J, Kongnakorn T, Detzel P, Sirisomboonwong K, Wasiak R. Direct medical costs associated with atopic diseases among young children in Thailand. J Med Econ. 2012; 15:1025–1035.

Article9. Kang KH, Kim KW, Kim DH. Utilization pattern and cost of medical treatment and complementary alternative therapy in children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2012; 22:27–36.

Article10. von Berg A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Kramer U, Link E, Bollrath C, Brockow I, Koletzko S, Grubl A, Heinrich J, Wichmann HE, Bauer CP, Reinhardt D, Berdel D. GINIplus study group. Preventive effect of hydrolyzed infant formulas persists until age 6 years: long-term results from the German Infant Nutritional Intervention Study (GINI). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008; 121:1442–1447.

Article11. von Berg A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Kramer U, Hoffmann B, Link E, Beckmann C, Hoffmann U, Reinhardt D, Grubl A, Heinrich J, Wichmann HE, Bauer CP, Koletzko S, Berdel D; GINIplus study group. Allergies in high-risk schoolchildren after early intervention with cow's milk protein hydrolysates: 10-year results from the German Infant Nutritional Intervention (GINI) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013; 131:1565–1573.

Article12. Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Allergy and Immunology. Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics. 2008; 121:183–191.

Article13. Halken S, Host A, Hansen LG, Osterballe O. Effect of an allergy prevention programme on incidence of atopic symptoms in infancy. A prospective study of 159 "high-risk" infants. Allergy. 1992; 47:545–553.14. Host A, Halken S, Muraro A, Dreborg S, Niggemann B, Aalberse R, Arshad SH, von Berg A, Carlsen KH, Duschen K, Eigenmann PA, Hill D, Jones C, Mellon M, Oldeus G, Oranje A, Pascual C, Prescott S, Sampson H, Svartengren M, Wahn U, Warner JA, Warner JO, Vandenplas Y, Wickman M, Zeiger RS. Dietary prevention of allergic diseases in infants and small children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008; 19:1–4.15. World Health Organization. Infant and young child nutrition: global strategy on infant and young child feeding. Report by the Secretariat. Fifty-fifth World Health Assembly. Provisional agenda item 13.10. Geneva: World Health Organization;2002. 04. 16.16. Hays T, Wood RA. A systematic review of the role of hydrolyzed infant formulas in allergy prevention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005; 159:810–816.

Article17. Jin YY, Cao MYR, Chen J, Kaku Y, Wu J, Cheng Y, Shimizu T, Takase M, Wu SM, Chen TX. Partially hydrolyzed cow's milk formula has a therapeutic effect on the infants with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011; 22:688–694.

Article18. von Berg A, Koletzko S, Grubl A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Wichmann HE, Bauer CP, Reinhardt D, Berdel D. German Infant Nutritional Intervention Study Group. The effect of hydrolyzed cow's milk formula for allergy prevention in the first year of life: the German Infant Nutritional Intervention Study, a randomized double-blind trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003; 111:533–540.

Article19. Alexander DD, Cabana MD. Partially hydrolyzed 100% whey protein infant formula and reduced risk of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010; 50:422–430.

Article20. Chan YH, Shek LP, Aw M, Quak SH, Lee BW. Use of hypoallergenic formula in the prevention of atopic disease among Asian children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002; 38:84–88.

Article21. Szajewska H, Horvath A. Meta-analysis of the evidence for a partially hydrolyzed 100% whey formula for the prevention of allergic diseases. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010; 26:423–437.

Article22. Host A, Koletzko B, Dreborg S, Muraro A, Wahn U, Aggett P, Bresson JL, Hernell O, Lafeber H, Michaelsen KF, Micheli JL, Rigo J, Weaver L, Heymans H, Strobel S, Vandenplas Y. Dietary products used in infants for treatment and prevention of food allergy. Joint Statement of the European Society for Paediatric Allergology and Clinical Immunology (ESPACI) Committee on Hypoallergenic Formulas and the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition. Arch Dis Child. 1999; 81:80–84.

Article23. NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel. Boyce JA, Assa'ad A, Burks AW, Jones SM, Sampson HA, Wood RA, Plaut M, Cooper SF, Fenton MJ, Arshad SH, Bahna SL, Beck LA, Byrd-Bredbenner C, Camargo CA Jr, Eichenfield L, Furuta GT, Hanifin JM, Jones C, Kraft M, Levy BD, Lieberman P, Luccioli S, McCall KM, Schneider LC, Simon RA, Simons FE, Teach SJ, Yawn BP, Schwaninger JM. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 126:6 Suppl. S1–S58.24. Fleischer DM, Spergel JM, Assa'ad AH, Pongracic JA. Primary prevention of allergic disease through nutritional interventions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013; 1:29–36.

Article25. Iskedjian M, Belli D, Farah B, Navarro V, Detzel P. Economic evaluation of a 100% whey-based partially hydrolyzed infant formula in the prevention of atopic dermatitis among Swiss children. J Med Econ. 2012; 15:378–393.

Article26. Iskedjian M, Dupont C, Spieldenner J, Kanny G, Raynaud F, Farah B, Haschke F. Economic evaluation of a 100% whey-based, partially hydrolysed formula in the prevention of atopic dermatitis among French children. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010; 26:2607–2626.

Article27. Iskedjian M, Haschke F, Farah B, van Odijk J, Berbari J, Spieldenner J. Economic evaluation of a 100% whey-based partially hydrolyzed infant formula in the prevention of atopic dermatitis among Danish children. J Med Econ. 2012; 15:394–408.

Article28. Iskedjian M, Szajewska H, Spieldenner J, Farah B, Berbari J. Metaanalysis of a partially hydrolysed 100%-whey infant formula vs. extensively hydrolysed infant formulas in the prevention of atopic dermatitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010; 26:2599–2606.

Article29. Su J, Prescott S, Sinn J, Tang M, Smith P, Heine RG, Spieldenner J, Iskedjian M. Cost-effectiveness of partially-hydrolyzed formula for prevention of atopic dermatitis in Australia. J Med Econ. 2012; 15:1064–1077.

Article30. Mertens J, Stock S, Lungen M, von Berg A, Kramer U, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Heinrich J, Koletzko S, Grubl A, Wichmann HE, Bauer CP, Reinhardt D, Berdel D, Gerber A. Is prevention of atopic eczema with hydrolyzed formulas cost-effective? A health economic evaluation from Germany. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012; 23:597–604.

Article31. Bhanegaonkar AJ, Horodniceanu EG, Gonzalez RR, Canlas Dizon MV, Detzel P, Erdogan-Ciftci E, Verheggen B, Botteman MF. Cost-effectiveness of partially hydrolyzed whey protein formula in the primary prevention of atopic dermatitis in at-risk urban filipino infants. Value Health Reg Issues. 2014; 3:124–135.

Article32. Beck JR, Pauker SG. The Markov process in medical prognosis. Med Decis Making. 1983; 3:419–458.

Article33. Sonnenberg FA, Beck JR. Markov models in medical decision making: a practical guide. Med Decis Making. 1993; 13:322–338.34. Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, Feldman SR, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL, Berger TG, Bergman JN, Cohen DE, Cooper KD, Cordoro KM, Davis DM, Krol A, Margolis DJ, Paller AS, Schwarzenberger K, Silverman RA, Williams HC, Elmets CA, Block J, Harrod CG, Smith Begolka W, Sidbury R. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:338–351.35. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993; 186:23–31.36. Pitt M, Garside R, Stein K. A cost-utility analysis of pimecrolimus vs. topical corticosteroids and emollients for the treatment of mild and moderate atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2006; 154:1137–1146.

Article37. Stevens KJ, Brazier JE, McKenna SP, Doward LC, Cork MJ. The development of a preference-based measure of health in children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2005; 153:372–377.

Article38. Leung R, Ho P. Asthma, allergy, and atopy in three south-east Asian populations. Thorax. 1994; 49:1205–1210.

Article39. Odhiambo JA, Williams HC, Clayton TO, Robertson CF, Asher MI. ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC phase three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 124:1251–1258.e23.

Article40. Chan YC, Tay YK, Sugito TL, Boediardja SA, Chau DD, Nguyen KV, Yee KC, Alias M, Hussein S, Dizon MV, Roa F, Chan YH, Wananukul S, Kullavanijaya P, Singalavanija S, Cheong WK. A study on the knowledge, attitudes and practices of Southeast Asian dermatologists in the management of atopic dermatitis. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006; 35:794–803.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Short-term Effect of Partially Hydrolyzed Formula on the Prevention of Development of Atopic Dermatitis in Infants at High Risk

- Effects of Breastfeeding on the Development of Allergies

- Relationship between Atopic Dermatitis, Wheezing during Infancy and Asthma Development

- The Influence of Breastfeeding and Weaning Practices on the Development of Allergic Disease Review of Current Evidence

- A perspective on partially hydrolyzed protein infant formula in nonexclusively breastfed infants