Korean J Ophthalmol.

2017 Aug;31(4):328-335. 10.3341/kjo.2016.0024.

Impact of Age on Scleral Buckling Surgery for Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea. jlee@pusan.ac.kr

- 2Department of Ophthalmology, Research Institute for Convergence of Biomedical Science and Technology, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Yangsan, Korea.

- 3Medical Research Institute, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea.

- KMID: 2385582

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/kjo.2016.0024

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The purpose of this study is to investigate new prognostic factors in associated with primary anatomical failure after scleral buckling (SB) for uncomplicated rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD).

METHODS

The medical records of patients with uncomplicated RRD treated with SB were retrospectively reviewed. Eyes with known prognostic factors for RRD, such as fovea-on, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, pseudophakia, aphakia, multiple breaks, or media opacity, were excluded. Analysis was performed to find correlations between anatomical success and various parameters, including age.

RESULTS

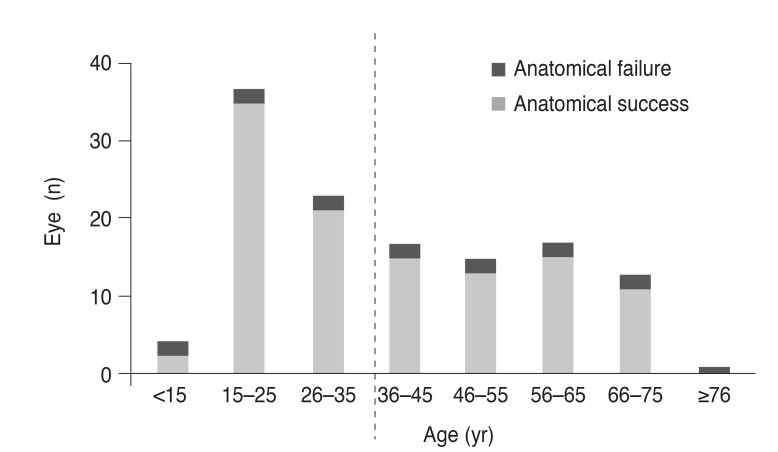

This study analyzed 127 eyes. Binary logistic regression analysis revealed that older age (≥35) was the sole independent prognostic factor (odds ratio, 3.5; p = 0.022). Older age was correlated with worse preoperative visual acuity (p < 0.001), shorter symptom duration (p < 0.001), presence of a large tear (p < 0.001), subretinal fluid drainage (p < 0.001), postoperative macular complications (p = 0.048), and greater visual improvement (p = 0.003).

CONCLUSIONS

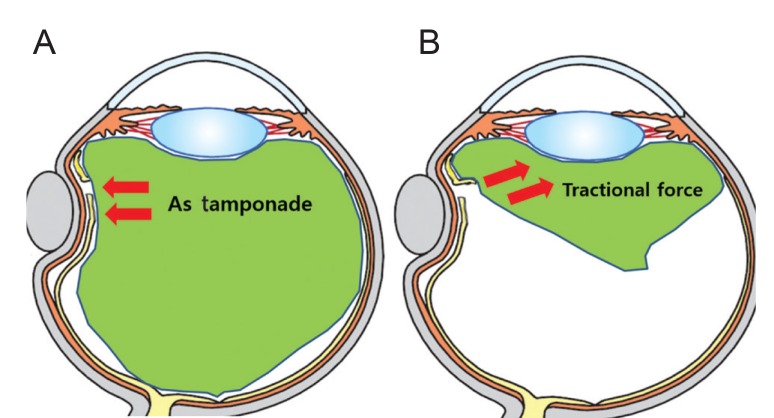

Older age (≥35) was an independent prognostic factor for primary anatomical failure in SB for uncomplicated RRD. The distinguished features of RRD between older and younger patients suggest that vitreous liquefaction and posterior vitreous detachment are important features associated with variation in surgical outcomes.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Pastor JC, Fernandez I, Rodriguez de la Rua E, et al. Surgical outcomes for primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachments in phakic and pseudophakic patients: the Retina 1 Project. Report 2. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008; 92:378–382. PMID: 18303159.2. Afrashi F, Akkin C, Egrilmez S, et al. Anatomic outcome of scleral buckling surgery in primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Int Ophthalmol. 2005; 26:77–81. PMID: 16957875.

Article3. Heimann H, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Bornfeld N, et al. Scleral buckling versus primary vitrectomy in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a prospective randomized multicenter clinical study. Ophthalmology. 2007; 114:2142–2154. PMID: 18054633.4. Sharma YR, Karunanithi S, Azad RV, et al. Functional and anatomic outcome of scleral buckling versus primary vitrectomy in pseudophakic retinal detachment. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005; 83:293–297. PMID: 15948779.

Article5. Feltgen N, Heimann H, Hoerauf H, et al. Scleral buckling versus primary vitrectomy in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment study (SPR study): risk assessment of anatomical outcome. SPR study report no. 7. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013; 91:282–287. PMID: 22336429.

Article6. Schneider EW, Geraets RL, Johnson MW. Pars plana vitrectomy without adjuvant procedures for repair of primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Retina. 2012; 32:213–219. PMID: 21811205.

Article7. Wong CW, Wong WL, Yeo IY, et al. Trends and factors related to outcomes for primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment surgery in a large Asian tertiary eye center. Retina. 2014; 34:684–692. PMID: 24169100.

Article8. Cheng SF, Yang CH, Lee CH, et al. Anatomical and functional outcome of surgery of primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in high myopic eyes. Eye (Lond). 2008; 22:70–76. PMID: 16858430.

Article9. Park SJ, Choi NK, Park KH, Woo SJ. Five year nationwide incidence of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment requiring surgery in Korea. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e80174. PMID: 24236173.

Article10. Thelen U, Amler S, Osada N, Gerding H. Success rates of retinal buckling surgery: relationship to refractive error and lens status: results from a large German case series. Ophthalmology. 2010; 117:785–790. PMID: 20207006.

Article11. Mitry D, Singh J, Yorston D, et al. The predisposing pathology and clinical characteristics in the Scottish retinal detachment study. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:1429–1434. PMID: 21561662.

Article12. Hagimura N, Suto K, Iida T, Kishi S. Optical coherence tomography of the neurosensory retina in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000; 129:186–190. PMID: 10682971.

Article13. Burton TC. Recovery of visual acuity after retinal detachment involving the macula. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1982; 80:475–497. PMID: 6763802.14. Shechtman DL, Dunbar MT. The expanding spectrum of vitreomacular traction. Optometry. 2009; 80:681–687. PMID: 19932441.

Article15. Moshfeghi AA, Salam GA, Deramo VA, et al. Management of macular holes that develop after retinal detachment repair. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003; 136:895–899. PMID: 14597042.

Article16. Benzerroug M, Genevois O, Siahmed K, et al. Results of surgery on macular holes that develop after rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008; 92:217–219. PMID: 18227202.

Article17. Garcia-Arumi J, Boixadera A, Martinez-Castillo V, et al. Macular holes after rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair: surgical management and functional outcome. Retina. 2011; 31:1777–1782. PMID: 21606891.18. Uemura A, Ideta H, Nagasaki H, et al. Macular pucker after retinal detachment surgery. Ophthalmic Surg. 1992; 23:116–119. PMID: 1549287.

Article19. Veckeneer M, Derycke L, Lindstedt EW, et al. Persistent subretinal fluid after surgery for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: hypothesis and review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012; 250:795–802. PMID: 22234351.

Article20. Morgan IG, Ohno-Matsui K, Saw SM, Miki D. Myopia. Lancet. 2012; 379:1739–1748. PMID: 22559900.

Article21. Miki D, Hida T, Hotta K, et al. Comparison of scleral buckling and vitrectomy for retinal detachment resulting from flap tears in superior quadrants. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2001; 45:187–191. PMID: 11313053.

Article22. Tani P, Robertson DM, Langworthy A. Prognosis for central vision and anatomic reattachment in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment with macula detached. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981; 92:611–620. PMID: 7304687.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Comparative Analysis of Scleral Buckling With or Without Postoperative Photocoagulation

- Delayed Absorption of Subretinal Fluid after Scleral Buckling Procedure for Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment

- Clinical Analysis of Laser Photocoagulation Following Scleral Buckling for the Treatment of Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment

- The Results of Primary Vitrectomy for Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment

- Preferences for Treatment Modalities of Simple Rhegmatogenous Tetinal Detachment in Korea