Korean J Crit Care Med.

2017 May;32(2):133-141. 10.4266/kjccm.2016.01011.

A Pilot Study of the Effectiveness of Medical Emergency System Implementation at a Single Center in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Pulmonology, Department of Internal Medicine, Institute of Chest Diseases, Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. chungks@yuhs.ac

- 2Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Ewha Medical Research Institute, Ewha Womans University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Division of Medical Information and Technology, Yonsei University Health System, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2384038

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4266/kjccm.2016.01011

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

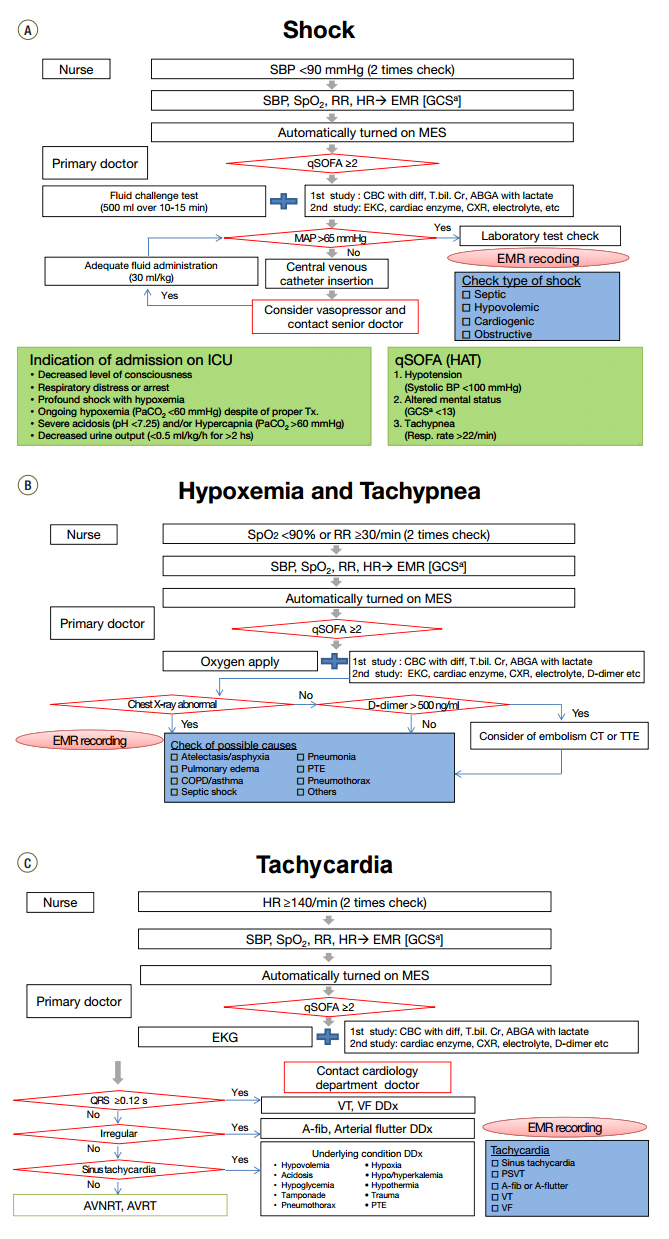

An automatic alarm system was developed was developed for unexpected vital sign instability in admitted patients to reduce staffing needs and costs related to rapid response teams. This was a pilot study of the automatic alarm system, the medical emergency system (MES), and the aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness of the MES before expanding this system to all departments.

METHODS

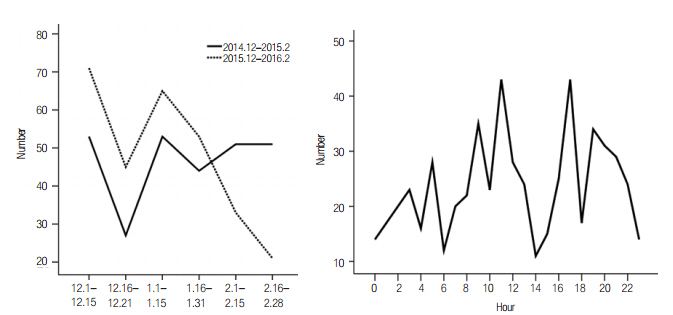

This retrospective, observational study compared the performance of patients admitted to the pulmonary department at a single center using patient data from three 3-month periods (before implementation of the MES, December 2013-February 2014; after implementation of the MES, December 2014-February 2015 and December 2015-February 2016).

RESULTS

A total of 571 patients were admitted to the pulmonary department during the three observation periods. During this pilot study, the MES automatically issued 568 alarms for 415 admitted patients. There was no significant difference in the rate of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) before and after application of the MES. The mortality rate also did not change. However, it appeared that CPR was prevented in four patients admitted from the general ward to the intensive care unit (ICU) during MES implementation. The median length of hospital stay and median length of ICU stay were not significantly different before and after MES implementation.

CONCLUSIONS

Although we did not find a significant improvement in outcomes upon MES implementation, the CPR rate and mortality rate did not increase despite increased comorbidities. This was a small pilot study and, based on these results, we believe that the MES may have significant effects in longer-term and larger-scale studies.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Rapid response systems in Korea

Bo Young Lee, Sang-Bum Hong

Acute Crit Care. 2019;34(2):108-116. doi: 10.4266/acc.2019.00535.

Reference

-

References

1. Kause J, Smith G, Prytherch D, Parr M, Flabouris A, Hillman K, et al. A comparison of antecedents to cardiac arrests, deaths and emergency intensive care admissions in Australia and New Zealand, and the United Kingdom: the ACADEMIA study. Resuscitation. 2004; 62:275–82.2. McQuillan P, Pilkington S, Allan A, Taylor B, Short A, Morgan G, et al. Confidential inquiry into quality of care before admission to intensive care. BMJ. 1998; 316:1853–8.

Article3. McGloin H, Adam SK, Singer M. Unexpected deaths and referrals to intensive care of patients on general wards: are some cases potentially avoidable? J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1999; 33:255–9.4. Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Briant R, Ali W, Scott A, Schug S. Adverse events in New Zealand public hospitals I: occurrence and impact. N Z Med J. 2002; 115:U271.5. Thomas EJ, Studdert DM, Burstin HR, Orav EJ, Zeena T, Williams EJ, et al. Incidence and types of adverse events and negligent care in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000; 38:261–71.

Article6. Brennan TA, Localio AR, Leape LL, Laird NM, Peterson L, Hiatt HH, et al. Identification of adverse events occurring during hospitalization. A crosssectional study of litigation, quality assurance, and medical records at two teaching hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 1990; 112:221–6.7. Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, Lawthers AG, Localio AR, Barnes BA, et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med. 1991; 324:377–84.8. Devita MA, Bellomo R, Hillman K, Kellum J, Rotondi A, Teres D, et al. Findings of the first consensus conference on medical emergency teams. Crit Care Mede. 2006; 34:2463–78.

Article9. Jones DA, DeVita MA, Bellomo R. Rapid-response teams. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:139–46.10. Chan PS, Jain R, Nallmothu BK, Berg RA, Sasson C. Rapid response teams: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010; 170:18–26.11. Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M, Bellomo R, Brown D, Doig G, et al. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005; 365:2091–7.12. Priestley G, Watson W, Rashidian A, Mozley C, Russell D, Wilson J, et al. Introducing critical care outreach: a ward-randomised trial of phased introduction in a general hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2004; 30:1398–404.

Article13. Jones CM, Bleyer AJ, Petree B. Evolution of a rapid response system from voluntary to mandatory activation. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010; 36:266–70.241.

Article14. Gerdik C, Vallish RO, Miles K, Godwin SA, Wludyka PS, Panni MK. Successful implementation of a family and patient activated rapid response team in an adult level 1 trauma center. Resuscitation. 2010; 81:1676–81.

Article15. Brunsveld-Reinders AH, Ludikhuize J, Dijkgraaf MG, Arbous MS, de Jonge E; COMET study group. Unexpected versus all-cause mortality as the endpoint for investigating the effects of a rapid response system in hospitalized patients. Crit Care. 2016; 20:168.

Article16. Maharaj R, Raffaele I, Wendon J. Rapid response systems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2015; 19:254.

Article17. Winters BD, Weaver SJ, Pfoh ER, Yang T, Pham JC, Dy SM. Rapid-response systems as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013; 158(5 Pt 2):417–25.18. Sandroni C, D’Arrigo S, Antonelli M. Rapid response systems: are they really effective? Crit Care. 2015; 19:104.

Article19. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987; 40:373–83.

Article20. Santamaria J, Tobin A, Holmes J. Changing cardiac arrest and hospital mortality rates through a medical emergency team takes time and constant review. Crit Care Med. 2010; 38:445–50.

Article21. Buist M, Harrison J, Abaloz E, Van Dyke S. Six year audit of cardiac arrests and medical emergency team calls in an Australian outer metropolitan teaching hospital. BMJ. 2007; 335:1210–2.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Regionalization of emergency medical system and re-establishment of regional emergency medical plan

- Effect of a new handover system for 119 transfer patients in a single emergency medical center

- Korean hospitalist system implementation and development strategies based on pilot studies

- Improvement of Night Pharmacy Service by Automated Dispensing Cabinet System Implementation in Emergency Medical Center

- Background and necessity of implementing the subspecialty of pediatric emergency medicine in Korea