Lab Med Online.

2017 Jul;7(3):94-102. 10.3343/lmo.2017.7.3.94.

Current Status of Standard Diagnostics and Treatment for Malaria, Tuberculosis, and Hepatitis in Myanmar

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Medical Environmental Biology and Tropical Medicine, School of Medicine, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 2International Tuberculosis Research Center (ITRC), Changwon, Korea.

- 3Department of Molecular Biology, College of Natural Science, Pusan National University, Busan, Korea.

- 4Department of Laboratory Medicine, School of Medicine, Pusan National University, Busan, Korea. cchl@pusan.ac.kr

- 5Department of Medical Research, Yangon, Myanmar.

- KMID: 2383087

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3343/lmo.2017.7.3.94

Abstract

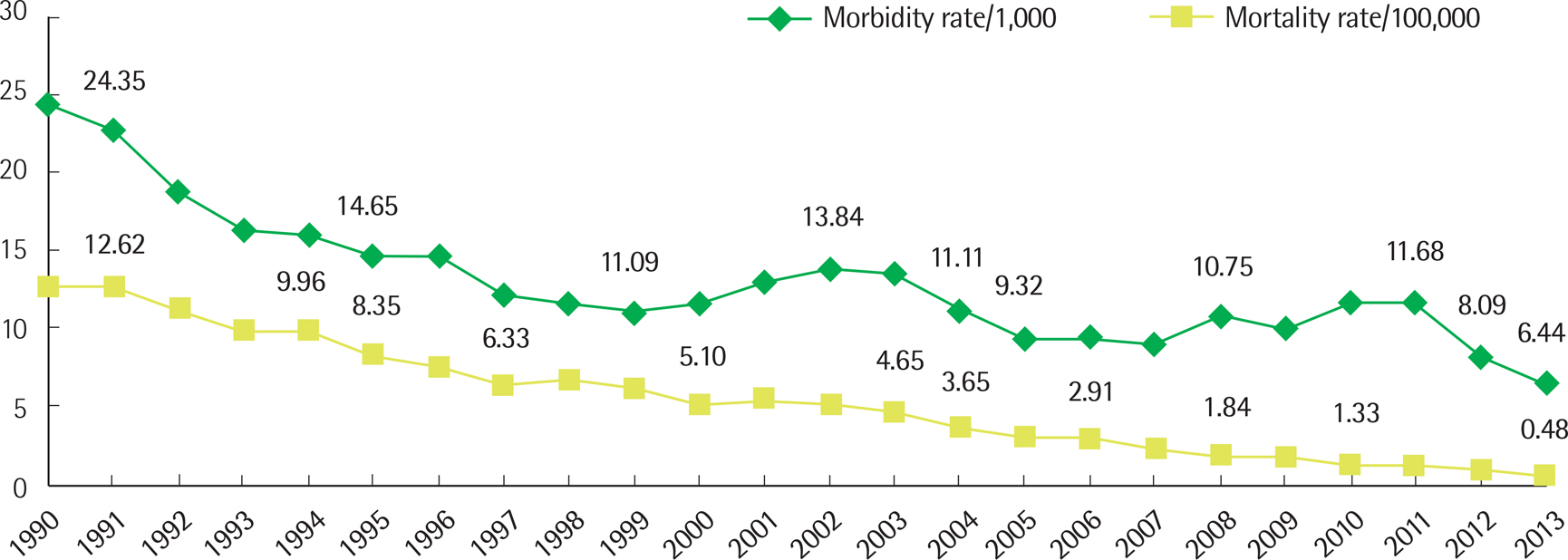

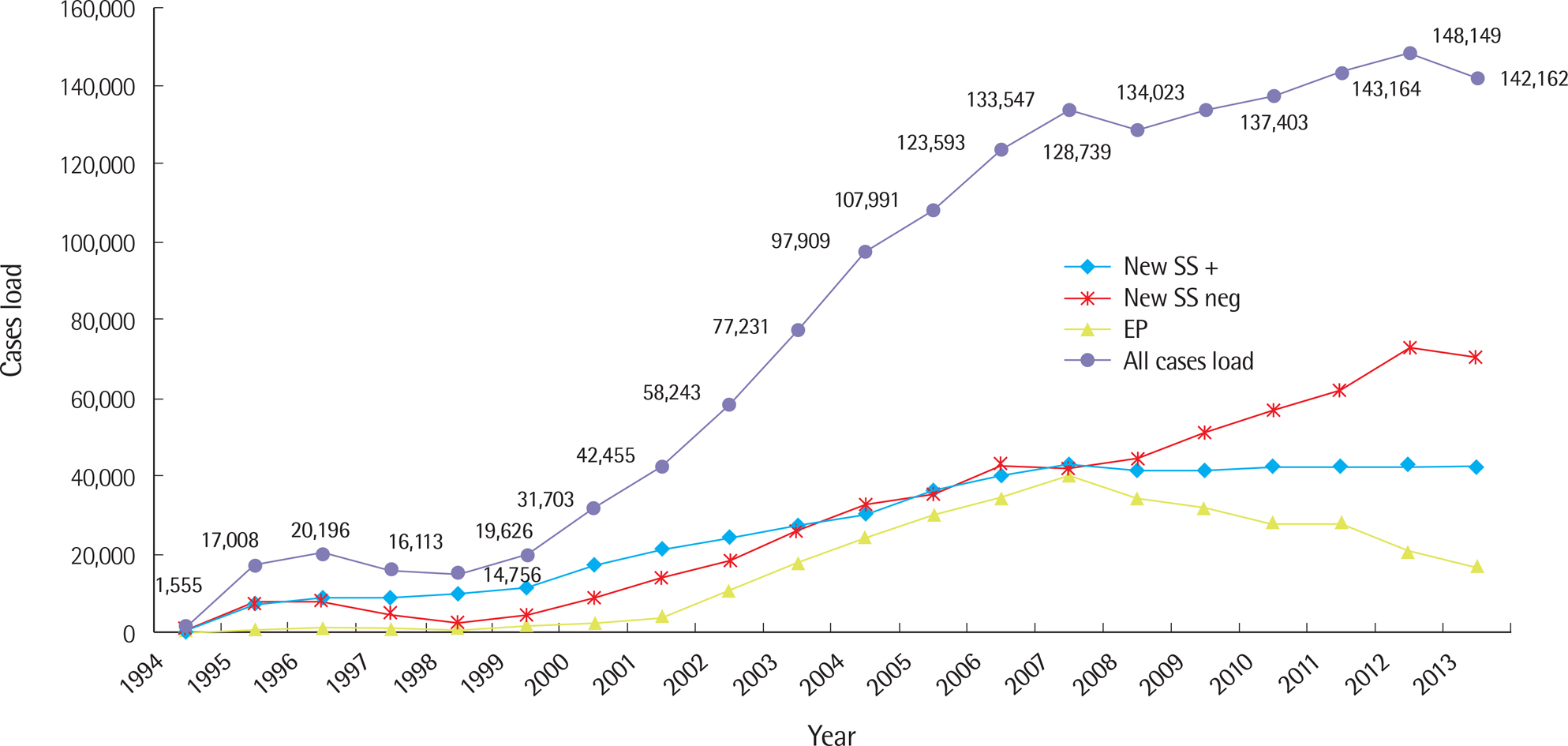

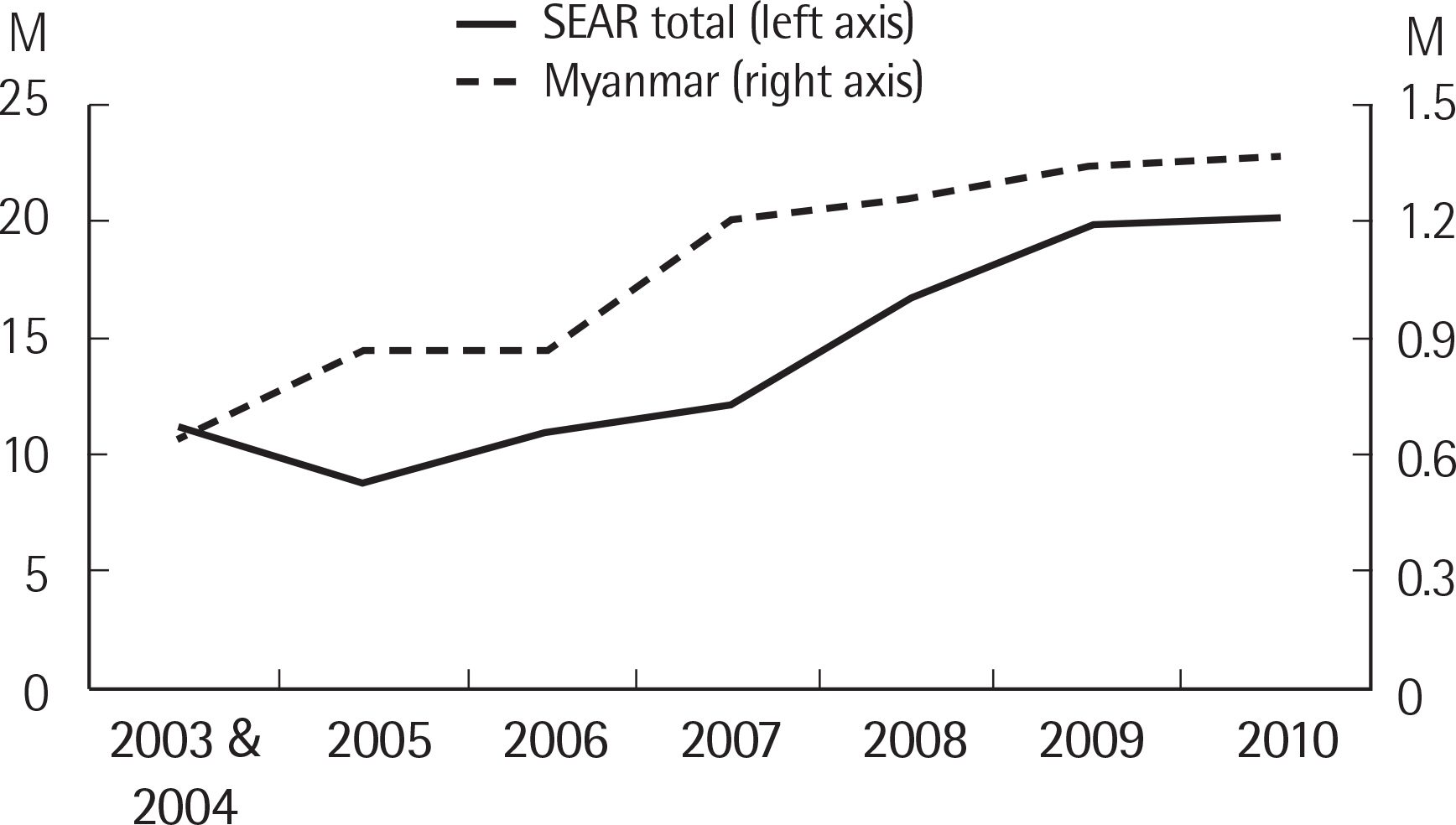

- Malaria, tuberculosis, and hepatitis are common and notorious infectious diseases in Myanmar. Despite intensive efforts to control these diseases, their prevalence remains high. For malaria, which is a vector-borne disease, a remarkable success in the reduction of new cases has been achieved. However, the annual number of tuberculosis cases has increased over the last few decades, and the prevalence of chronic viral hepatitis infection has been high in Myanmar and other nearby countries. Early detection and prompt treatment are crucial to control these diseases. We have devoted our research efforts to understanding the status of these infectious diseases and working towards their eventual elimination for the last four years with the support of the Korea International Cooperation Agency. In the modern era, an infection that develops in one geographical area can spread globally because national borders do not effectively limit disease transmission. Our efforts to understand the status of infectious diseases in Myanmar will benefit not only Myanmar but also neighboring countries such as Korea.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Bank, World Development Indicators 2014 (Myanmar). http://data.worldbank.org/country/myanmar.2. Kwon S, Kim TH. International Cooperation for Health Sector Development in Myanmar. Korea Institute for International Economy Policy, and Market Economic Research Institute. 2014.

Article3. Ministry of Health. Health in Myanmar, 2013. Ministry of Health, The Union of The Republic of Myanmar. 2013.4. National Health Plan (2006-2011), Ministry of Health, The Union of The Republic of Myanmar. 2006.5. Cho HK, Kim JR, Kim SY, Kyaw YY, Win AA, Cheong JH. Sorafenib suppresses hepatitis B virus gene expression via inhibiting JNK pathway. Hepatoma Res. 2015; 1:97–103.

Article6. Aung WW, Ei PW, Nyunt WW, Swe TL, Lwin T, Htwe MM, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Myanmar. Ann Lab Med. 2015; 35:494–9.

Article7. Nyunt MH, Kyaw MP, Thant KZ, Shein T, Han SS, Zaw NN, et al. Effective high-throughput blood pooling strategy before DNA extraction for detection of malaria in low-transmission settings. Korean J Parasi-tol. 2016; 54:253–9.

Article8. Ei PW, Aung WW, Lee JS, Choi GE, Chang CL. Molecular strain typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a review of frequently used methods. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31:1673–83.9. Ministry of Health. Health in Myanmar, 2014. Ministry of Health, The Union of The Republic of Myanmar. 2014.10. Vector Borne Diseases Center Report 2014. Ministry of Health, The Union of The Republic of Myanmar. 2014.11. World Health Organization. Strategic framework for artemisinin resistance containment in Myanmar (MARC) 2011-2015. World Health Organization, 2011.http://www.searo.who.int/myanmar/documents/MARCframeworkApril2011.pdf?ua=1.12. Kyaw MP, Nyunt MH, Chit K, Aye MM, Aye KH, Lindegardh N, et al. Reduced susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to artesunate in southern Myanmar. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e57689.

Article13. Nyunt MH, Hlaing T, Oo HW, Tin-Oo LL, Phway HP, Wang B, et al. Molecular assessment of artemisinin resistance markers, polymorphisms in the K13 propeller, and a multidrug-resistance gene in the eastern and western border areas of Myanmar. Clin Infect Dis. 2015; 60:1208–15.

Article14. World Health Organization. Developing a national strategy for malaria elimination in Myanmar. World Health Organization, 2015.http://www.searo.who.int/myanmar/areas/malaria_workshopfornsp/en/.15. World Health Organization. Strategy for malaria elimination in the Greater Mekong Subregion (2015–2030). World Health Organization Regional Offce for the Western Pacifc, 2015.http://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/10945/9789290617181_eng.pdf?sequence=1.16. World Health Organization. Global TB report 2015. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/191102/1/9789241565059_eng.pdf.17. Ministry of Health, Myanmar. National TB program Myanmar. Annual report 2013. In. Ministry of Health, The Union of The Republic of Myanmar. 2014.18. National TB Controllers Association/CDC Advisory Group on Tuberculosis Genotyping. Guide to the application of genotyping to tuberculosis prevention and control. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. 2004.19. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the management of MDR-TB in Myanmar. World Health Organization, 2013.http://www.searo.who.int/myanmar/areas/GuidelinesforMDRTB.pdf?ua=1. (updated on May 2013).20. Stop TB Partnership. The Operational Strategy 2016-2020. http://www.stoptb.org/about/operationalStrategy.asp.21. World Health Organization. Prevention and Control of Viral Hepatitis Infection: Framework for Global Action. Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/hepatitis/Framework/en/.22. Mohd Hanaf ah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specifc antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013; 57:1333–42.23. Jacobsen KH, Wiersma ST. Hepatitis A virus seroprevalence by age and world region, 1990 and 2005. Vaccine. 2010; 28:6635–7.

Article24. World Health Organization Regional Offce for South-East Asia. Viral hepatitis in the World Health Organization South-East Asia Region. 2011.http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/206521. (updated on 2011).25. World Health Organization Regional Offce for South-East Asia. Regional strategy for the prevention and control of viral hepatitis. World Health Organization, 1998.http://www.searo.who.int/entity/emerging_diseases/topics/CD_282.pdf.26. Khin M, Min AM, Kyaw YY, Kyaw MTH, Oo KM, Kyi KP. Bibliography of research fndings on liver diseases in Myanmar. Department of Medical Research, The Union of The Republic of Myanmar. 2005.27. Kyi KP, Win KM. Viral hepatitis in Myanmar. DMR Bulletin. 1995; 9:1–31.28. Lwin AA, Aye KS, Htun MM, Kyaw YY, Zaw KK, Aung TT, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C infection in Myanmar. 44th Myanmar Health Congress Program. 2016; 27.29. Shinji T, Kyaw YY, Gokan K, Tanaka Y, Ochi K, Kusano N, et al. Analysis of HCV genotypes from blood donors shows three new HCV type 6 subgroups exist in Myanmar. Acta Med Okayama. 2004; 58:135–42.30. Win KM. Hepatitis C tratment in Myanmar. Singapore Hepatitis Conference. 2015.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Indication and survival among liver transplant patients in Yangon Speciality Hospital, Myanmar

- Posttransplantation tuberculosis management in terms of immunosuppressant cost: a case report in Myanmar

- Status of Vivax Malaria in the Republic of Korea

- Spatiotemporal Trends of Malaria in Relation to Economic Development and Cross-Border Movement along the China–Myanmar Border in Yunnan Province

- The management of chronic hepatitis C