Int J Stem Cells.

2015 May;8(1):24-35. 10.15283/ijsc.2015.8.1.24.

Regulation of Stem Cell Fate by ROS-mediated Alteration of Metabolism

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Veterinary Physiology, College of Veterinary Medicine and Research Institute for Veterinary Science, and BK21 PLUS Creative Veterinary Research Center, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea. hjhan@snu.ac.kr

- KMID: 2380796

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.15283/ijsc.2015.8.1.24

Abstract

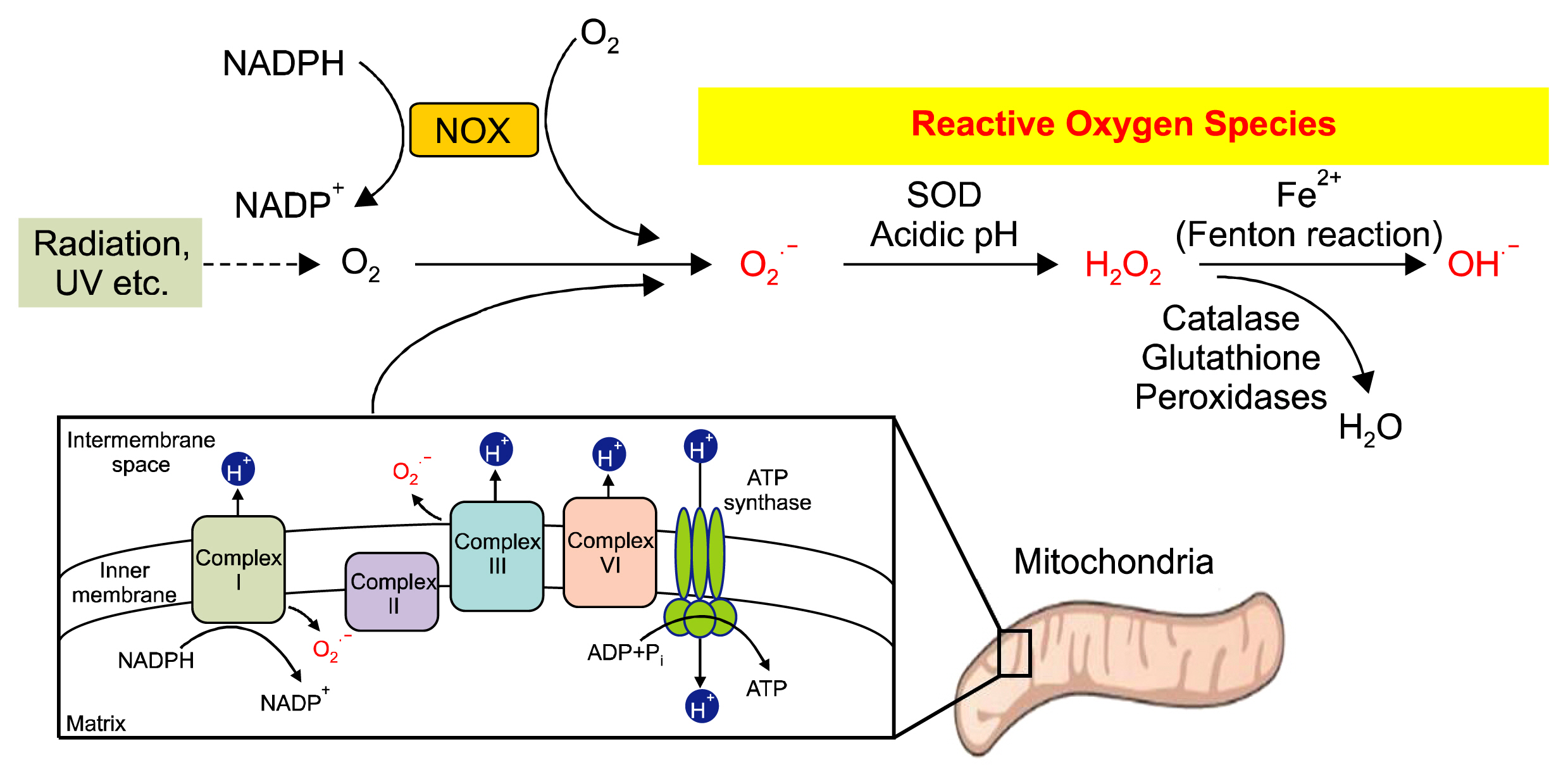

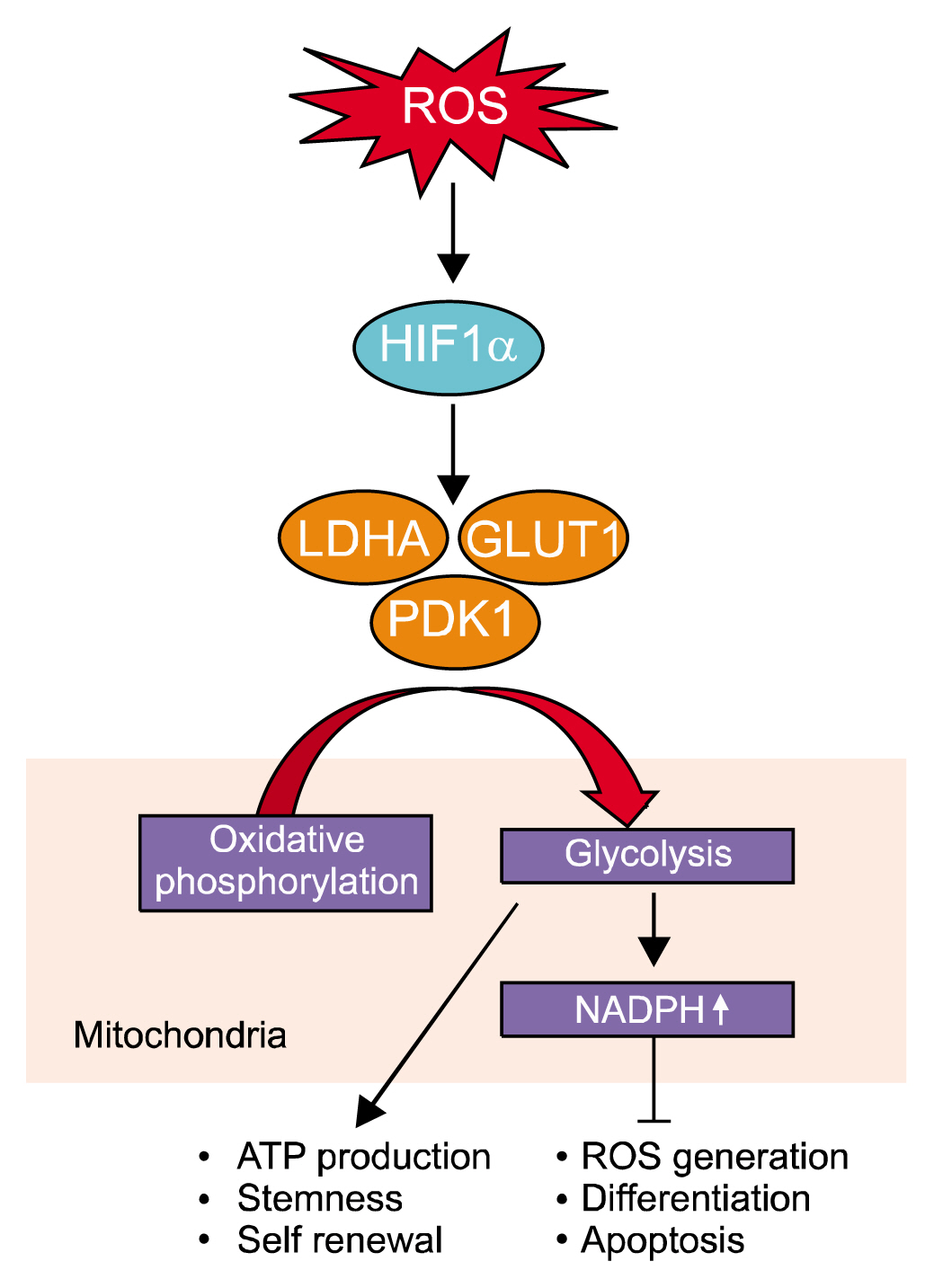

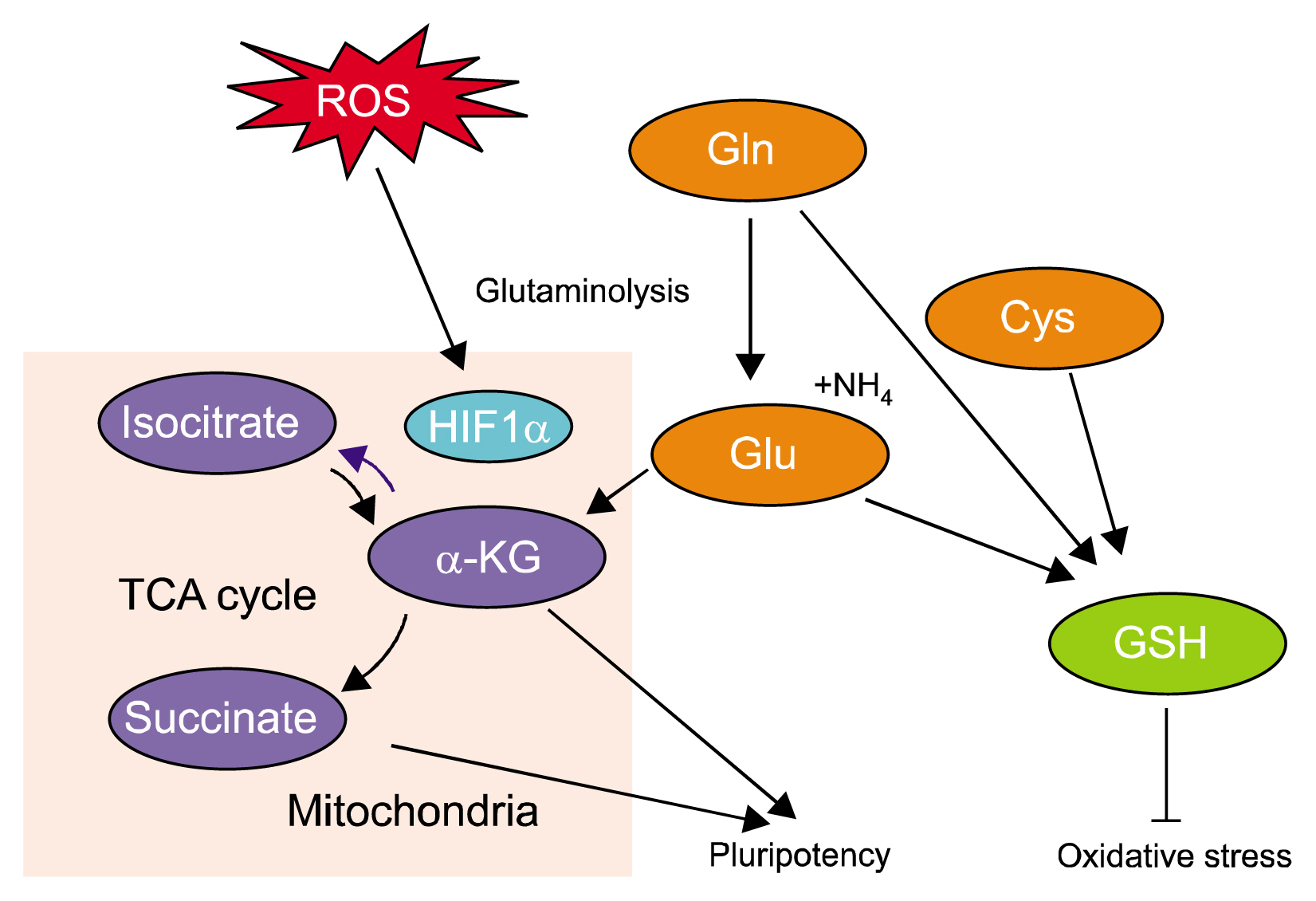

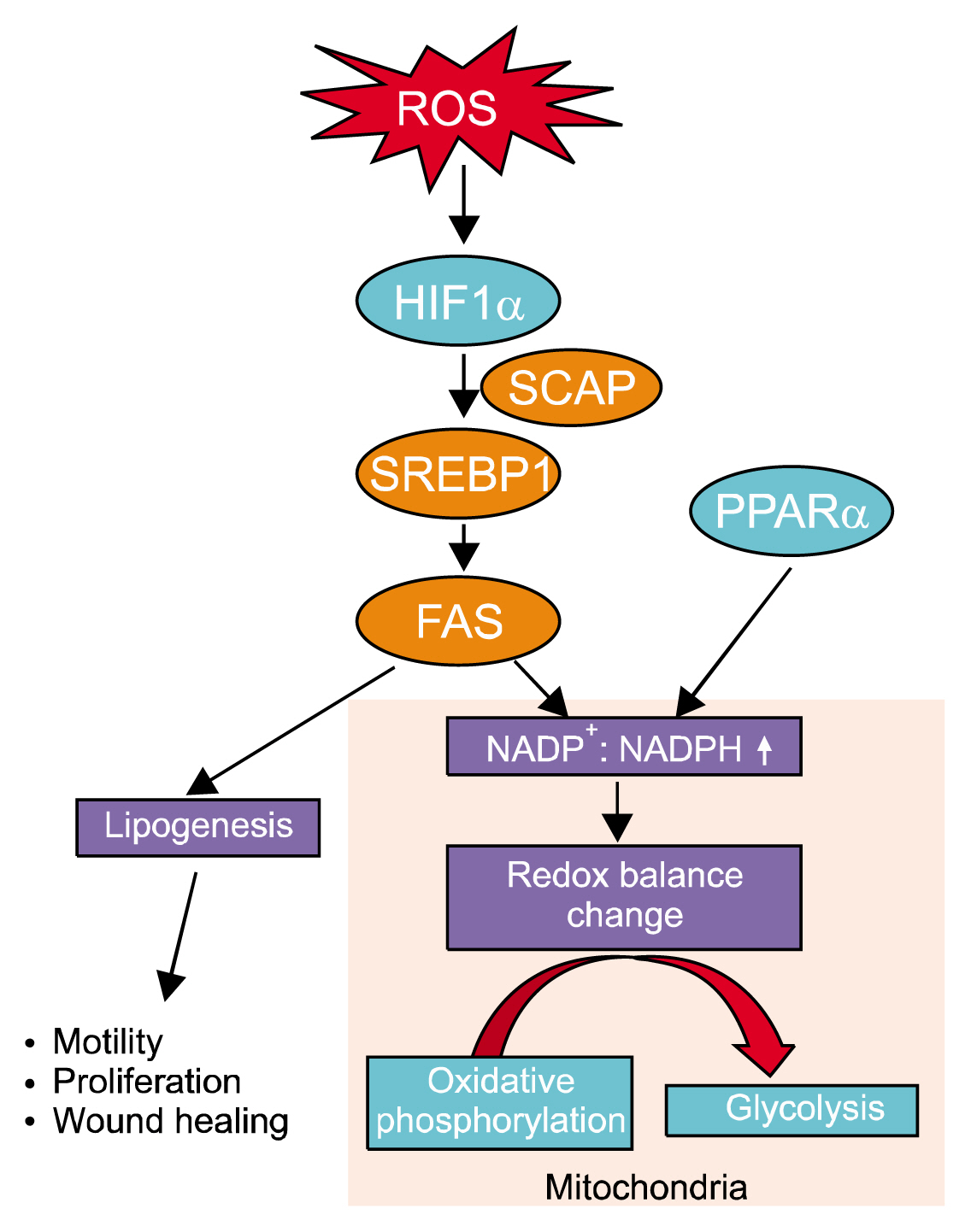

- Stem cells have attracted much attention due to their distinct features that support infinite self-renewal and differentiation into the cellular derivatives of three lineages. Recent studies have suggested that many stem cells both embryonic and adult stem cells reside in a specialized niche defined by hypoxic condition. In this respect, distinguishing functional differences arising from the oxygen concentration is important in understanding the nature of stem cells and in controlling stem cell fate for therapeutic purposes. ROS act as cellular signaling molecules involved in the propagation of signaling and the translation of environmental cues into cellular responses to maintain cellular homeostasis, which is mediated by the coordination of various cellular processes, and to adapt cellular activity to available bioenergetic sources. Thus, in this review, we describe the physiological role of ROS in stem cell fate and its effect on the metabolic regulation of stem cells.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Simon MC, Keith B. The role of oxygen availability in embryonic development and stem cell function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008; 9:285–296. PMID: 18285802. PMCID: 2876333.

Article2. Harris JM, Esain V, Frechette GM, Harris LJ, Cox AG, Cortes M, Garnaas MK, Carroll KJ, Cutting CC, Khan T, Elks PM, Renshaw SA, Dickinson BC, Chang CJ, Murphy MP, Paw BH, Vander Heiden MG, Goessling W, North TE. Glucose metabolism impacts the spatiotemporal onset and magnitude of HSC induction in vivo. Blood. 2013; 121:2483–2493. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-471201. PMID: 23341543. PMCID: 3612858.

Article3. Hom JR, Quintanilla RA, Hoffman DL, de Mesy Bentley KL, Molkentin JD, Sheu SS, Porter GA Jr. The permeability transition pore controls cardiac mitochondrial maturation and myocyte differentiation. Dev Cell. 2011; 21:469–478. PMID: 21920313. PMCID: 3175092.

Article4. Holmström KM, Finkel T. Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014; 15:411–421. PMID: 24854789.

Article5. Liang R, Ghaffari S. Stem cells, redox signaling, and stem cell aging. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014; 20:1902–1916. PMID: 24383555. PMCID: 3967383.

Article6. Gomes AP, Price NL, Ling AJ, Moslehi JJ, Montgomery MK, Rajman L, White JP, Teodoro JS, Wrann CD, Hubbard BP, Mercken EM, Palmeira CM, de Cabo R, Rolo AP, Turner N, Bell EL, Sinclair DA. Declining NAD+ induces a pseudohypoxic state disrupting nuclear-mitochondrial communication during aging. Cell. 2013; 155:1624–1638. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.037. PMID: 24360282. PMCID: 4076149.

Article7. Rimmelé P, Bigarella CL, Liang R, Izac B, Dieguez-Gonzalez R, Barbet G, Donovan M, Brugnara C, Blander JM, Sinclair DA, Ghaffari S. Aging-like phenotype and defective lineage specification in SIRT1-deleted hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2014; 3:44–59. DOI: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.04.015. PMID: 25068121. PMCID: 4110778.

Article8. Zachar V, Duroux M, Emmersen J, Rasmussen JG, Pennisi CP, Yang S, Fink T. Hypoxia and adipose-derived stem cell-based tissue regeneration and engineering. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2011; 11:775–786. PMID: 21413910.

Article9. Eliasson P, Jönsson JI. The hematopoietic stem cell niche: low in oxygen but a nice place to be. J Cell Physiol. 2010; 222:17–22.

Article10. Harrison JS, Rameshwar P, Chang V, Bandari P. Oxygen saturation in the bone marrow of healthy volunteers. Blood. 2002; 99:394. DOI: 10.1182/blood.V99.1.394. PMID: 11783438.

Article11. Ivanovic Z. Hypoxia or in situ normoxia: The stem cell paradigm. J Cell Physiol. 2009; 219:271–275. DOI: 10.1002/jcp.21690. PMID: 19160417.

Article12. Mohyeldin A, Garzón-Muvdi T, Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Oxygen in stem cell biology: a critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2010; 7:150–161. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.007. PMID: 20682444.

Article13. Dhimitruka I, Bobko AA, Eubank TD, Komarov DA, Khramtsov VV. Phosphonated trityl probes for concurrent in vivo tissue oxygen and pH monitoring using electron paramagnetic resonance-based techniques. J Am Chem Soc. 2013; 135:5904–5910. DOI: 10.1021/ja401572r. PMID: 23517077. PMCID: 3982387.

Article14. Kaewsuwan S, Song SY, Kim JH, Sung JH. Mimicking the functional niche of adipose-derived stem cells for regenerative medicine. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012; 12:1575–1588. DOI: 10.1517/14712598.2012.721763. PMID: 22953993.

Article15. Rodesch F, Simon P, Donner C, Jauniaux E. Oxygen measurements in endometrial and trophoblastic tissues during early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1992; 80:283–285. PMID: 1635745.16. Ezashi T, Das P, Roberts RM. Low O2 tensions and the prevention of differentiation of hES cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005; 102:4783–4788. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0501283102. PMID: 15772165. PMCID: 554750.

Article17. Närvä E, Pursiheimo JP, Laiho A, Rahkonen N, Emani MR, Viitala M, Laurila K, Sahla R, Lund R, Lähdesmäki H, Jaakkola P, Lahesmaa R. Continuous hypoxic culturing of human embryonic stem cells enhances SSEA-3 and MYC levels. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e78847. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078847. PMID: 24236059. PMCID: 3827269.

Article18. Pollard PJ, Kranc KR. Hypoxia signaling in hematopoietic stem cells: a double-edged sword. Cell Stem Cell. 2010; 7:276–278. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.006. PMID: 20804963.

Article19. Lee SH, Lee MY, Han HJ. Short-period hypoxia increases mouse embryonic stem cell proliferation through cooperation of arachidonic acid and PI3K/Akt signalling pathways. Cell Prolif. 2008; 41:230–247. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00516.x. PMID: 18336469.

Article20. Lee SH, Lee YJ, Han HJ. Role of hypoxia-induced fibronectin-integrin β1 expression in embryonic stem cell proliferation and migration: Involvement of PI3K/Akt and FAK. J Cell Physiol. 2011; 226:484–493. DOI: 10.1002/jcp.22358.

Article21. Finkel T. Oxidant signals and oxidative stress. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003; 15:247–254. DOI: 10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00002-4. PMID: 12648682.

Article22. Janssen-Heininger YM, Mossman BT, Heintz NH, Forman HJ, Kalyanaraman B, Finkel T, Stamler JS, Rhee SG, van der Vliet A. Redox-based regulation of signal transduction: principles, pitfalls, and promises. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008; 45:1–17. DOI: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.03.011. PMID: 18423411. PMCID: 2453533.

Article23. Dröge W. Aging-related changes in the thiol/disulfide redox state: implications for the use of thiol antioxidants. Exp Gerontol. 2002; 37:1333–1345. DOI: 10.1016/S0531-5565(02)00175-4.

Article24. Tahara EB, Navarete FD, Kowaltowski AJ. Tissue-, substrate-, and site-specific characteristics of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009; 46:1283–1297. DOI: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.008. PMID: 19245829.

Article25. Brand MD. The sites and topology of mitochondrial super-oxide production. Exp Gerontol. 2010; 45:466–472. DOI: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.003. PMID: 20064600. PMCID: 2879443.

Article26. Mailloux RJ, Harper ME. Mitochondrial proticity and ROS signaling: lessons from the uncoupling proteins. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 23:451–458. DOI: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.04.004. PMID: 22591987.

Article27. Rustin P, Munnich A, Rötig A. Succinate dehydrogenase and human diseases: new insights into a well-known enzyme. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002; 10:289–291. DOI: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200793. PMID: 12082502.

Article28. Nathan C, Cunningham-Bussel A. Beyond oxidative stress: an immunologist's guide to reactive oxygen species. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013; 13:349–361. DOI: 10.1038/nri3423. PMID: 23618831. PMCID: 4250048.

Article29. Forman HJ, Kennedy J. Superoxide production and electron transport in mitochondrial oxidation of dihydroorotic acid. J Biol Chem. 1975; 250:4322–4326. PMID: 165196.

Article30. Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V. Generation of reactive oxygen species in the reaction catalyzed by α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. J Neurosci. 2004; 24:7771–7778. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1842-04.2004. PMID: 15356188.

Article31. Gazaryan IG, Krasnikov BF, Ashby GA, Thorneley RN, Kristal BS, Brown AM. Zinc is a potent inhibitor of thiol oxidoreductase activity and stimulates reactive oxygen species production by lipoamide dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 2002; 277:10064–10072. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M108264200.

Article32. Anastasiou D, Poulogiannis G, Asara JM, Boxer MB, Jiang JK, Shen M, Bellinger G, Sasaki AT, Locasale JW, Auld DS, Thomas CJ, Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC. Inhibition of pyruvate kinase M2 by reactive oxygen species contributes to cellular antioxidant responses. Science. 2011; 334:1278–1283. DOI: 10.1126/science.1211485. PMID: 22052977. PMCID: 3471535.

Article33. Sarbassov DD, Sabatini DM. Redox regulation of the nutrient-sensitive raptor-mTOR pathway and complex. J Biol Chem. 2005; 280:39505–39509. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M506096200. PMID: 16183647.

Article34. Dansen TB, Smits LM, van Triest MH, de Keizer PL, van Leenen D, Koerkamp MG, Szypowska A, Meppelink A, Brenkman AB, Yodoi J, Holstege FC, Burgering BM. Redox-sensitive cysteines bridge p300/CBP-mediated acetylation and FoxO4 activity. Nat Chem Biol. 2009; 5:664–672. DOI: 10.1038/nchembio.194. PMID: 19648934.

Article35. Guo Z, Kozlov S, Lavin MF, Person MD, Paull TT. ATM activation by oxidative stress. Science. 2010; 330:517–521. DOI: 10.1126/science.1192912. PMID: 20966255.

Article36. Guo YL, Chakraborty S, Rajan SS, Wang R, Huang F. Effects of oxidative stress on mouse embryonic stem cell proliferation, apoptosis, senescence, and self-renewal. Stem Cells Dev. 2010; 19:1321–1331. DOI: 10.1089/scd.2009.0313. PMID: 20092403. PMCID: 3128305.

Article37. Forsyth NR, Musio A, Vezzoni P, Simpson AH, Noble BS, McWhir J. Physiologic oxygen enhances human embryonic stem cell clonal recovery and reduces chromosomal abnormalities. Cloning Stem Cells. 2006; 8:16–23. DOI: 10.1089/clo.2006.8.16. PMID: 16571074.

Article38. Urao N, Ushio-Fukai M. Redox regulation of stem/progenitor cells and bone marrow niche. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013; 54:26–39. DOI: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.10.532. PMCID: 3637653.

Article39. Folmes CD, Dzeja PP, Nelson TJ, Terzic A. Metabolic plasticity in stem cell homeostasis and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2012; 11:596–606. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.002. PMID: 23122287. PMCID: 3593051.

Article40. Prigione A, Fauler B, Lurz R, Lehrach H, Adjaye J. The senescence-related mitochondrial/oxidative stress pathway is repressed in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010; 28:721–733. DOI: 10.1002/stem.404. PMID: 20201066.

Article41. Zhang J, Khvorostov I, Hong JS, Oktay Y, Vergnes L, Nuebel E, Wahjudi PN, Setoguchi K, Wang G, Do A, Jung HJ, McCaffery JM, Kurland IJ, Reue K, Lee WN, Koehler CM, Teitell MA. UCP2 regulates energy metabolism and differentiation potential of human pluripotent stem cells. EMBO J. 2011; 30:4860–4873. PMID: 22085932. PMCID: 3243621.

Article42. Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell. 2012; 21:297–308. DOI: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014. PMID: 22439925. PMCID: 3311998.

Article43. Mandal S, Lindgren AG, Srivastava AS, Clark AT, Banerjee U. Mitochondrial function controls proliferation and early differentiation potential of embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2011; 29:486–495. DOI: 10.1002/stem.590. PMID: 21425411. PMCID: 4374603.

Article44. Zhou W, Choi M, Margineantu D, Margaretha L, Hesson J, Cavanaugh C, Blau CA, Horwitz MS, Hockenbery D, Ware C, Ruohola-Baker H. HIF1α induced switch from bivalent to exclusively glycolytic metabolism during ESC- to-EpiSC/hESC transition. EMBO J. 2012; 31:2103–2116. PMID: 22446391. PMCID: 3343469.

Article45. Han MK, Song EK, Guo Y, Ou X, Mantel C, Broxmeyer HE. SIRT1 regulates apoptosis and Nanog expression in mouse embryonic stem cells by controlling p53 subcellular localization. Cell Stem Cell. 2008; 2:241–251. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.002. PMID: 18371449. PMCID: 2819008.

Article46. Zhang X, Yalcin S, Lee DF, Yeh TY, Lee SM, Su J, Mungamuri SK, Rimmelé P, Kennedy M, Sellers R, Landthaler M, Tuschl T, Chi NW, Lemischka I, Keller G, Ghaffari S. FOXO1 is an essential regulator of pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2011; 13:1092–1099. PMID: 21804543. PMCID: 4053529.

Article47. van den Berg MC, Burgering BM. Integrating opposing signals toward Forkhead box O. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011; 14:607–621.

Article48. Shenoy A, Blelloch RH. Regulation of microRNA function in somatic stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014; 15:565–576. PMID: 25118717. PMCID: 4377327.

Article49. Kim BS, Jung JS, Jang JH, Kang KS, Kang SK. Nuclear Argonaute 2 regulates adipose tissue-derived stem cell survival through direct control of miR10b and selenoprotein N1 expression. Aging Cell. 2011; 10:277–291. DOI: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00670.x. PMID: 21241449.

Article50. Xu J, Huang Z, Lin L, Fu M, Gao Y, Shen Y, Zou Y, Sun A, Qian J, Ge J. miR-210 over-expression enhances mesenchymal stem cell survival in an oxidative stress environment through antioxidation and c-Met pathway activation. Sci China Life Sci. 2014; 57:989–997. PMID: 25168379.

Article51. Shepard TH, Muffley LA, Smith LT. Mitochondrial ultra-structure in embryos after implantation. Hum Reprod. 2000; 15( Suppl 2):218–228. DOI: 10.1093/humrep/15.suppl_2.218.

Article52. Armstrong L, Tilgner K, Saretzki G, Atkinson SP, Stojkovic M, Moreno R, Przyborski S, Lako M. Human induced pluripotent stem cell lines show stress defense mechanisms and mitochondrial regulation similar to those of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010; 28:661–673. DOI: 10.1002/stem.307. PMID: 20073085.

Article53. Chen CT, Shih YR, Kuo TK, Lee OK, Wei YH. Coordinated changes of mitochondrial biogenesis and anti-oxidant enzymes during osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008; 26:960–968. DOI: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0509. PMID: 18218821.

Article54. Sena LA, Chandel NS. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell. 2012; 48:158–167. DOI: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.025. PMID: 23102266. PMCID: 3484374.

Article55. Buggisch M, Ateghang B, Ruhe C, Strobel C, Lange S, Wartenberg M, Sauer H. Stimulation of ES-cell-derived cardiomyogenesis and neonatal cardiac cell proliferation by reactive oxygen species and NADPH oxidase. J Cell Sci. 2007; 120:885–894. DOI: 10.1242/jcs.03386. PMID: 17298980.

Article56. Sharifpanah F, Wartenberg M, Hannig M, Piper HM, Sauer H. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α agonists enhance cardiomyogenesis of mouse ES cells by utilization of a reactive oxygen species-dependent mechanism. Stem Cells. 2008; 26:64–71. DOI: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0532.

Article57. Crespo FL, Sobrado VR, Gomez L, Cervera AM, McCreath KJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species mediate cardiomyocyte formation from embryonic stem cells in high glucose. Stem Cells. 2010; 28:1132–1142. PMID: 20506541.

Article58. Xiao Q, Luo Z, Pepe AE, Margariti A, Zeng L, Xu Q. Embryonic stem cell differentiation into smooth muscle cells is mediated by Nox4-produced H2O2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009; 296:C711–C723. DOI: 10.1152/ajpcell.00442.2008.59. Kanda Y, Hinata T, Kang SW, Watanabe Y. Reactive oxygen species mediate adipocyte differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells. Life Sci. 2011; 89:250–258. DOI: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.06.007. PMID: 21722651.

Article60. Mouche S, Mkaddem SB, Wang W, Katic M, Tseng YH, Carnesecchi S, Steger K, Foti M, Meier CA, Muzzin P, Kahn CR, Ogier-Denis E, Szanto I. Reduced expression of the NADPH oxidase NOX4 is a hallmark of adipocyte differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007; 1773:1015–1027. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.03.003. PMID: 17553579.

Article61. Cho YM, Kwon S, Pak YK, Seol HW, Choi YM, Park do J, Park KS, Lee HK. Dynamic changes in mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant enzymes during the spontaneous differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006; 348:1472–1478. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.020. PMID: 16920071.

Article62. Facucho-Oliveira JM, Alderson J, Spikings EC, Egginton S, St John JC. Mitochondrial DNA replication during differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2007; 120:4025–4034. DOI: 10.1242/jcs.016972. PMID: 17971411.

Article63. Facucho-Oliveira JM, St John JC. The relationship between pluripotency and mitochondrial DNA proliferation during early embryo development and embryonic stem cell differentiation. Stem Cell Rev. 2009; 5:140–158. DOI: 10.1007/s12015-009-9058-0. PMID: 19521804.

Article64. Suhr ST, Chang EA, Tjong J, Alcasid N, Perkins GA, Goissis MD, Ellisman MH, Perez GI, Cibelli JB. Mitochondrial rejuvenation after induced pluripotency. PLoS One. 2010; 5:e14095. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014095. PMID: 21124794. PMCID: 2991355.

Article65. Ballabeni A, Park IH, Zhao R, Wang W, Lerou PH, Daley GQ, Kirschner MW. Cell cycle adaptations of embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108:19252–19257. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1116794108. PMID: 22084091. PMCID: 3228440.

Article66. Folmes CD, Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, Arrell DK, Lindor JZ, Dzeja PP, Ikeda Y, Perez-Terzic C, Terzic A. Somatic oxidative bioenergetics transitions into pluripotency-dependent glycolysis to facilitate nuclear reprogramming. Cell Metab. 2011; 14:264–271. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.011. PMID: 21803296. PMCID: 3156138.

Article67. Rehman J. Empowering self-renewal and differentiation: the role of mitochondria in stem cells. J Mol Med (Berl). 2010; 88:981–986. DOI: 10.1007/s00109-010-0678-2.

Article68. Varum S, Rodrigues AS, Moura MB, Momcilovic O, Easley CA 4th, Ramalho-Santos J, Van Houten B, Schatten G. Energy metabolism in human pluripotent stem cells and their differentiated counterparts. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e20914. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020914. PMID: 21698063. PMCID: 3117868.

Article69. Panopoulos AD, Yanes O, Ruiz S, Kida YS, Diep D, Tautenhahn R, Herrerías A, Batchelder EM, Plongthongkum N, Lutz M, Berggren WT, Zhang K, Evans RM, Siuzdak G, Izpisua Belmonte JC. The metabolome of induced pluripotent stem cells reveals metabolic changes occurring in somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Res. 2012; 22:168–177. DOI: 10.1038/cr.2011.177. PMCID: 3252494.

Article70. Kondoh H, Lleonart ME, Gil J, Wang J, Degan P, Peters G, Martinez D, Carnero A, Beach D. Glycolytic enzymes can modulate cellular life span. Cancer Res. 2005; 65:177–185. PMID: 15665293.71. Filosa S, Fico A, Paglialunga F, Balestrieri M, Crooke A, Verde P, Abrescia P, Bautista JM, Martini G. Failure to increase glucose consumption through the pentose-phosphate pathway results in the death of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase gene-deleted mouse embryonic stem cells subjected to oxidative stress. Biochem J. 2003; 370:935–943.

Article72. Forristal CE, Wright KL, Hanley NA, Oreffo RO, Houghton FD. Hypoxia inducible factors regulate pluripotency and proliferation in human embryonic stem cells cultured at reduced oxygen tensions. Reproduction. 2010; 139:85–97. DOI: 10.1530/REP-09-0300.

Article73. Lee SH, Heo JS, Han HJ. Effect of hypoxia on 2-deoxy-glucose uptake and cell cycle regulatory protein expression of mouse embryonic stem cells: involvement of Ca2+/PKC, MAPKs and HIF-1α. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2007; 19:269–282.

Article74. Yoshida Y, Takahashi K, Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Hypoxia enhances the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009; 5:237–241. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.001. PMID: 19716359.

Article75. Maynard S, Swistowska AM, Lee JW, Liu Y, Liu ST, Da Cruz AB, Rao M, de Souza-Pinto NC, Zeng X, Bohr VA. Human embryonic stem cells have enhanced repair of multiple forms of DNA damage. Stem Cells. 2008; 26:2266–2274. DOI: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1041. PMID: 18566332. PMCID: 2574957.

Article76. Saretzki G, Walter T, Atkinson S, Passos JF, Bareth B, Keith WN, Stewart R, Hoare S, Stojkovic M, Armstrong L, von Zglinicki T, Lako M. Downregulation of multiple stress defense mechanisms during differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008; 26:455–464. DOI: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0628.

Article77. Hansson J, Rafiee MR, Reiland S, Polo JM, Gehring J, Okawa S, Huber W, Hochedlinger K, Krijgsveld J. Highly coordinated proteome dynamics during reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Rep. 2012; 2:1579–1592. PMID: 23260666. PMCID: 4438680.

Article78. Kobayashi CI, Suda T. Regulation of reactive oxygen species in stem cells and cancer stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2012; 227:421–430.

Article79. Suda T, Takubo K, Semenza GL. Metabolic regulation of hematopoietic stem cells in the hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2011; 9:298–310. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.010. PMID: 21982230.

Article80. Kocabas F, Zheng J, Thet S, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, DeBerardinis RJ, Zhang C, Sadek HA. Meis1 regulates the metabolic phenotype and oxidant defense of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2012; 120:4963–4972. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-432260. PMID: 22995899. PMCID: 3525021.

Article81. Zhang CC, Sadek HA. Hypoxia and metabolic properties of hematopoietic stem cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014; 20:1891–1901. DOI: 10.1089/ars.2012.5019. PMCID: 3967354.

Article82. Candelario KM, Shuttleworth CW, Cunningham LA. Neural stem/progenitor cells display a low requirement for oxidative metabolism independent of hypoxia inducible factor-1α expression. J Neurochem. 2013; 125:420–429. DOI: 10.1111/jnc.12204. PMID: 23410250. PMCID: 4204647.

Article83. Fehrer C, Brunauer R, Laschober G, Unterluggauer H, Reitinger S, Kloss F, Gülly C, Gassner R, Lepperdinger G. Reduced oxygen tension attenuates differentiation capacity of human mesenchymal stem cells and prolongs their lifespan. Aging Cell. 2007; 6:745–757. DOI: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00336.x. PMID: 17925003.

Article84. Ryu JM, Han HJ. L-threonine regulates G1/S phase transition of mouse embryonic stem cells via PI3K/Akt, MAPKs, and mTORC pathways. J Biol Chem. 2011; 286:23667–23678. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M110.216283. PMID: 21550972. PMCID: 3129147.

Article85. Wang J, Alexander P, Wu L, Hammer R, Cleaver O, McKnight SL. Dependence of mouse embryonic stem cells on threonine catabolism. Science. 2009; 325:435–439. DOI: 10.1126/science.1173288. PMID: 19589965. PMCID: 4373593.

Article86. Ito K, Suda T. Metabolic requirements for the maintenance of self-renewing stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014; 15:243–256. DOI: 10.1038/nrm3772. PMID: 24651542. PMCID: 4095859.

Article87. Carey BW, Finley LW, Cross JR, Allis CD, Thompson CB. Intracellular α-ketoglutarate maintains the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2015; 518:413–416. DOI: 10.1038/nature13981.

Article88. Gao P, Tchernyshyov I, Chang TC, Lee YS, Kita K, Ochi T, Zeller KI, De Marzo AM, Van Eyk JE, Mendell JT, Dang CV. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009; 458:762–765. DOI: 10.1038/nature07823. PMID: 19219026. PMCID: 2729443.

Article89. Son J, Lyssiotis CA, Ying H, Wang X, Hua S, Ligorio M, Perera RM, Ferrone CR, Mullarky E, Shyh-Chang N, Kang Y, Fleming JB, Bardeesy N, Asara JM, Haigis MC, DePinho RA, Cantley LC, Kimmelman AC. Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS-regulated metabolic pathway. Nature. 2013; 496:101–105. DOI: 10.1038/nature12040. PMID: 23535601. PMCID: 3656466.

Article90. Wise DR, DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Sayed N, Zhang XY, Pfeiffer HK, Nissim I, Daikhin E, Yudkoff M, McMahon SB, Thompson CB. Myc regulates a transcriptional program that stimulates mitochondrial glutaminolysis and leads to glutamine addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008; 105:18782–18787. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0810199105. PMID: 19033189. PMCID: 2596212.

Article91. Häberle J, Görg B, Rutsch F, Schmidt E, Toutain A, Benoist JF, Gelot A, Suc AL, Höhne W, Schliess F, Häussinger D, Koch HG. Congenital glutamine deficiency with glutamine synthetase mutations. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:1926–1933. PMID: 16267323.

Article92. Häberle J, Görg B, Toutain A, Rutsch F, Benoist JF, Gelot A, Suc AL, Koch HG, Schliess F, Häussinger D. Inborn error of amino acid synthesis: human glutamine synthetase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006; 29:352–358. PMID: 16763901.

Article93. Holleran AL, Briscoe DA, Fiskum G, Kelleher JK. Glutamine metabolism in AS-30D hepatoma cells. Evidence for its conversion into lipids via reductive carboxylation. Mol Cell Biochem. 1995; 152:95–101. PMID: 8751155.

Article94. Metallo CM, Gameiro PA, Bell EL, Mattaini KR, Yang J, Hiller K, Jewell CM, Johnson ZR, Irvine DJ, Guarente L, Kelleher JK, Vander Heiden MG, Iliopoulos O, Stephanopoulos G. Reductive glutamine metabolism by IDH1 mediates lipogenesis under hypoxia. Nature. 2011; 481:380–384. PMID: 22101433. PMCID: 3710581.

Article95. Wise DR, Ward PS, Shay JE, Cross JR, Gruber JJ, Sachdeva UM, Platt JM, DeMatteo RG, Simon MC, Thompson CB. Hypoxia promotes isocitrate dehydrogenase-dependent carboxylation of α-ketoglutarate to citrate to support cell growth and viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108:19611–19616. PMID: 22106302. PMCID: 3241793.

Article96. Ferber EC, Peck B, Delpuech O, Bell GP, East P, Schulze A. FOXO3a regulates reactive oxygen metabolism by inhibiting mitochondrial gene expression. Cell Death Differ. 2012; 19:968–979. PMCID: 3354049.

Article97. Jensen KS, Binderup T, Jensen KT, Therkelsen I, Borup R, Nilsson E, Multhaupt H, Bouchard C, Quistorff B, Kjaer A, Landberg G, Staller P. FoxO3A promotes metabolic adaptation to hypoxia by antagonizing Myc function. EMBO J. 2011; 30:4554–4570. PMID: 21915097. PMCID: 3243591.

Article98. Whillier S, Garcia B, Chapman BE, Kuchel PW, Raftos JE. Glutamine and α-ketoglutarate as glutamate sources for glutathione synthesis in human erythrocytes. FEBS J. 2011; 278:3152–3163. PMID: 21749648.

Article99. Yeo H, Lyssiotis CA, Zhang Y, Ying H, Asara JM, Cantley LC, Paik JH. FoxO3 coordinates metabolic pathways to maintain redox balance in neural stem cells. EMBO J. 2013; 32:2589–2602. PMID: 24013118. PMCID: 3791369.

Article100. Kim YH, Heo JS, Han HJ. High glucose increase cell cycle regulatory proteins level of mouse embryonic stem cells via PI3-K/Akt and MAPKs signal pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2006; 209:94–102. PMID: 16775839.

Article101. Gameiro PA, Yang J, Metelo AM, Pérez-Carro R, Baker R, Wang Z, Arreola A, Rathmell WK, Olumi A, López-Larrubia P, Stephanopoulos G, Iliopoulos O. In vivo HIF-mediated reductive carboxylation is regulated by citrate levels and sensitizes VHL-deficient cells to glutamine deprivation. Cell Metab. 2013; 17:372–385. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.02.002. PMID: 23473032. PMCID: 4003458.

Article102. Pompéia C, Lopes LR, Miyasaka CK, Procópio J, Sannomiya P, Curi R. Effect of fatty acids on leukocyte function. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2000; 33:1255–1268. DOI: 10.1590/S0100-879X2000001100001. PMID: 11050654.

Article103. Kuhajda FP, Jenner K, Wood FD, Hennigar RA, Jacobs LB, Dick JD, Pasternack GR. Fatty acid synthesis: a potential selective target for antineoplastic therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994; 91:6379–6383. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6379. PMID: 8022791. PMCID: 44205.

Article104. Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007; 7:763–777. DOI: 10.1038/nrc2222. PMID: 17882277.

Article105. Li J, Bosch-Marce M, Nanayakkara A, Savransky V, Fried SK, Semenza GL, Polotsky VY. Altered metabolic responses to intermittent hypoxia in mice with partial deficiency of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Physiol Genomics. 2006; 25:450–457. DOI: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00293.2005. PMID: 16507783.

Article106. Lee HJ, Ryu JM, Jung YH, Oh SY, Lee SJ, Han HJ. Novel pathway for hypoxia-induced proliferation and migration in human mesenchymal stem cells: Involvement of HIF-1α, FASN, and mTORC1. Stem Cells. 2015; Epub ahead of print. DOI: 10.1002/stem.2020.

Article107. Pelicano H, Xu RH, Du M, Feng L, Sasaki R, Carew JS, Hu Y, Ramdas L, Hu L, Keating MJ, Zhang W, Plunkett W, Huang P. Mitochondrial respiration defects in cancer cells cause activation of Akt survival pathway through a redox-mediated mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2006; 175:913–923. DOI: 10.1083/jcb.200512100. PMID: 17158952. PMCID: 2064701.

Article108. Storz P. Forkhead homeobox type O transcription factors in the responses to oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011; 14:593–605. DOI: 10.1089/ars.2010.3405. PMCID: 3038124.

Article109. Essers MA, Weijzen S, de Vries-Smits AM, Saarloos I, de Ruiter ND, Bos JL, Burgering BM. FOXO transcription factor activation by oxidative stress mediated by the small GTPase Ral and JNK. EMBO J. 2004; 23:4802–4812. DOI: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600476. PMID: 15538382. PMCID: 535088.

Article110. Nakae J, Kitamura T, Kitamura Y, Biggs WH 3rd, Arden KC, Accili D. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 regulates adipocyte differentiation. Dev Cell. 2003; 4:119–129. DOI: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00401-X. PMID: 12530968.

Article111. Munekata K, Sakamoto K. Forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 is essential for adipocyte differentiation. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2009; 45:642–651. DOI: 10.1007/s11626-009-9230-5. PMID: 19585174.

Article112. Kojima T, Norose T, Tsuchiya K, Sakamoto K. Mouse 3T3-L1 cells acquire resistance against oxidative stress as the adipocytes differentiate via the transcription factor FoxO. Apoptosis. 2010; 15:83–93. DOI: 10.1007/s10495-009-0415-x.

Article113. Calzadilla P, Sapochnik D, Cosentino S, Diz V, Dicelio L, Calvo JC, Guerra LN. N-acetylcysteine reduces markers of differentiation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2011; 12:6936–6951. DOI: 10.3390/ijms12106936. PMID: 22072928. PMCID: 3211019.

Article114. Krey G, Braissant O, L'Horset F, Kalkhoven E, Perroud M, Parker MG, Wahli W. Fatty acids, eicosanoids, and hypolipidemic agents identified as ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors by coactivator-dependent receptor ligand assay. Mol Endocrinol. 1997; 11:779–791. DOI: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0007. PMID: 9171241.

Article115. Calkin AC, Thomas MC. PPAR Agonists and Cardiovascular Disease in Diabetes. PPAR Res. 2008; 2008:245410. DOI: 10.1155/2008/245410. PMID: 18288280. PMCID: 2233765.

Article116. Vergori L, Lauret E, Gaceb A, Beauvillain C, Andriantsitohaina R, Martinez MC. PPARα regulates endothelial progenitor cell maturation and myeloid lineage differentiation through a NADPH oxidase-dependent mechanism in mice. Stem Cells. 2015; 33:1292–1303. DOI: 10.1002/stem.1924.

Article117. Madsen L, Petersen RK, Kristiansen K. Regulation of adipocyte differentiation and function by polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005; 1740:266–286. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.03.001. PMID: 15949694.

Article118. Poli G, Leonarduzzi G, Biasi F, Chiarpotto E. Oxidative stress and cell signalling. Curr Med Chem. 2004; 11:1163–1182. DOI: 10.2174/0929867043365323. PMID: 15134513.

Article119. Ryu JM, Baek YB, Shin MS, Park JH, Park SH, Lee JH, Han HJ. Sphingosine-1-phosphate-induced Flk-1 trans-activation stimulates mouse embryonic stem cell proliferation through S1P1/S1P3-dependent β-arrestin/c-Src pathways. Stem Cell Res. 2014; 12:69–85. DOI: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.08.013.

Article120. Ryu JM, Han HJ. Autotaxin-LPA axis regulates hMSC migration by adherent junction disruption and cytoskeletal rearrangement via LPAR1/3-dependent PKC/GSK3β/β-catenin and PKC/Rho GTPase pathways. Stem Cells. 2015; 33:819–832. DOI: 10.1002/stem.1882.

Article121. Park SS, Kim MO, Yun SP, Ryu JM, Park JH, Seo BN, Jeon JH, Han HJ. C16-Ceramide-induced F-actin regulation stimulates mouse embryonic stem cell migration: involvement of N-WASP/Cdc42/Arp2/3 complex and cofilin-1/α-actinin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013; 1831:350–360.

Article122. Bigarella CL, Liang R, Ghaffari S. Stem cells and the impact of ROS signaling. Development. 2014; 141:4206–4218. DOI: 10.1242/dev.107086. PMID: 25371358. PMCID: 4302918.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Regulating T Cell-mediated Immunity and Disease

- Regulation of Neural Stem Cell Fate by Natural Products

- Stem Cell ; New Paradigm in the Era of Genomic Medicine

- Nuclear receptor regulation of stemness and stem cell differentiation

- Reactive oxygen species enhance differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into mesendodermal lineage