J Korean Med Sci.

2016 Jul;31(7):1020-1026. 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.7.1020.

Influence of Social Engagement on Mortality in Korea: Analysis of the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (2006-2012)

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea.

- 2Institute of Health Services Research, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea. ecpark@yuhs.ac

- 3Department of Hospital Management, Graduate School of Public Health, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Department of Public Health, Graduate School, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea.

- 5Institute on Aging, Ajou University Medical Center, Suwon, Korea.

- 6Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2373718

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.7.1020

Abstract

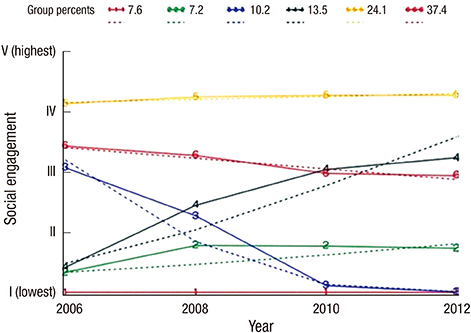

- The objective of this study was to investigate the impact of social engagement and patterns of change in social engagement over time on mortality in a large population, aged 45 years or older. Data from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging from 2006 and 2012 were assessed using longitudinal data analysis. We included 8,234 research subjects at baseline (2006). The primary analysis was based on Cox proportional hazards models to examine our hypothesis. The hazard ratio of all-cause mortality for the lowest level of social engagement was 1.841-times higher (P < 0.001) compared with the highest level of social engagement. Subgroup analysis results by gender showed a similar trend. A six-class linear solution fit the data best, and class 1 (the lowest level of social engagement class, 7.6% of the sample) was significantly related to the highest mortality (HR: 4.780, P < 0.001). Our results provide scientific insight on the effects of the specificity of the level of social engagement and changes in social engagement on all-cause mortality in current practice, which are important for all-cause mortality risk. Therefore, protection from all-cause mortality may depend on avoidance of constant low-levels of social engagement.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

The Association between Frequency of Social Contact and Frailty in Older People: Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study (KFACS)

Doukyoung Chon, Yunhwan Lee, Jinhee Kim, Kyung-eun Lee

J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(51):. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e332.

Reference

-

1. Landau R. Social integration in the second half of life. Soc Sci Med. 2003; 56:435–436.2. Berkman LF. The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosom Med. 1995; 57:245–254.3. Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000; 51:843–857.4. Choi Y, Park S, Cho KH, Chun SY, Park EC. A change in social activity affect cognitive function in middle-aged and older Koreans: analysis of a Korean longitudinal study on aging (2006-2012). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. Forthcoming. 2016.5. Choi Y, Park EC, Kim JH, Yoo KB, Choi JW, Lee KS. A change in social activity and depression among Koreans aged 45 years and more: analysis of the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (2006-2010). Int Psychogeriatr. 2015; 27:629–637.6. Lee GH, Kim CH, Shin HC, Park YW, Sung EJ. The relation of physical activity to helath related quality of life. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2007; 28:451–459.7. Brisette I, Cohen S, Seeman TE. Measuring social integration and social networks. In : Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social Support Measurement and Intervention: a Guide for Health and Social Scientistis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press;2000. p. 53–85.8. Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Giovannucci E, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. A prospective study of social networks in relation to total mortality and cardiovascular disease in men in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1996; 50:245–251.9. Kreibig SD, Whooley MA, Gross JJ. Social integration and mortality in patients with coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Psychosom Med. 2014; 76:659–668.10. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010; 7:e1000316.11. Broman CL. Social relationships and health-related behavior. J Behav Med. 1993; 16:335–350.12. Cohen S, Lemay EP. Why would social networks be linked to affect and health practices? Health Psychol. 2007; 26:410–417.13. Barth J, Schneider S, von Känel R. Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2010; 72:229–238.14. Ebrahim S, Wannamethee G, McCallum A, Walker M, Shaper AG. Marital status, change in marital status, and mortality in middle-aged British men. Am J Epidemiol. 1995; 142:834–842.15. Cerhan JR, Wallace RB. Change in social ties and subsequent mortality in rural elders. Epidemiology. 1997; 8:475–481.16. Ramsay S, Ebrahim S, Whincup P, Papacosta O, Morris R, Lennon L, Wannamethee SG. Social engagement and the risk of cardiovascular disease mortality: results of a prospective population-based study of older men. Ann Epidemiol. 2008; 18:476–483.17. Giles LC, Glonek GF, Luszcz MA, Andrews GR. Effect of social networks on 10 year survival in very old Australians: the Australian longitudinal study of aging. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005; 59:574–579.18. Berkman LF, Melchior M, Chastang JF, Niedhammer I, Leclerc A, Goldberg M. Social integration and mortality: a prospective study of French employees of Electricity of France-Gas of France: the GAZEL Cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2004; 159:167–174.19. Sugisawa H, Liang J, Liu X. Social networks, social support, and mortality among older people in Japan. J Gerontol. 1994; 49:S3–13.20. Lutgendorf SK, Russell D, Ullrich P, Harris TB, Wallace R. Religious participation, interleukin-6, and mortality in older adults. Health Psychol. 2004; 23:465–475.21. Walter-Ginzburg A, Blumstein T, Chetrit A, Modan B. Social factors and mortality in the old-old in Israel: the CALAS study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002; 57:S308–18.22. Litwin H. The association of disability, sociodemographic background, and social network type in later life. J Aging Health. 2003; 15:391–408.23. Burr JA, Tavares J, Mutchler JE. Volunteering and hypertension risk in later life. J Aging Health. 2011; 23:24–51.24. Musick MA, Herzog AR, House JS. Volunteering and mortality among older adults: findings from a national sample. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999; 54:S173–80.25. Berkman LF, Glass T. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In : Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press;2000. p. 137–173.26. Kamarck TW, Manuck SB, Jennings JR. Social support reduces cardiovascular reactivity to psychological challenge: a laboratory model. Psychosom Med. 1990; 52:42–58.27. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Garner W, Speicher C, Penn GM, Holliday J, Glaser R. Psychosocial modifiers of immunocompetence in medical students. Psychosom Med. 1984; 46:7–14.28. Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: a review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull. 1996; 119:488–531.29. Ford ES, Loucks EB, Berkman LF. Social integration and concentrations of C-reactive protein among US adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2006; 16:78–84.30. King DE, Mainous AG 3rd, Steyer TE, Pearson W. The relationship between attendance at religious services and cardiovascular inflammatory markers. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2001; 31:415–425.31. Väänänen A, Kouvonen A, Kivimäki M, Pentti J, Vahtera J. Social support, network heterogeneity, and smoking behavior in women: the 10-town study. Am J Health Promot. 2008; 22:246–255.32. Orth-Gomér K, Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L. Lack of social support and incidence of coronary heart disease in middle-aged Swedish men. Psychosom Med. 1993; 55:37–43.33. DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004; 23:207–218.34. Elder GH Jr, Shanahan MJ. The life course and human development. In : Lerner RM, Damon W, editors. The Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol 1. 6th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.;2006. p. 665–715.35. House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988; 241:540–545.36. Lund R, Modvig J, Due P, Holstein BE. Stability and change in structural social relations as predictor of mortality among elderly women and men. Eur J Epidemiol. 2000; 16:1087–1097.37. Eng PM, Rimm EB, Fitzmaurice G, Kawachi I. Social ties and change in social ties in relation to subsequent total and cause-specific mortality and coronary heart disease incidence in men. Am J Epidemiol. 2002; 155:700–709.38. George LK. Conceptualizing and measuring trajectories. In : Elder GH, Giele JZ, editors. The Craft of Life Course Research. New York, NY: Guilford Press;2009. p. 163–186.39. Nagin DS. Group-Based Modeling of Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press;2005.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Association of Social Support and Social Activity with Physical Functioning in Older Persons

- The Influence of Negative Mental Health on the Health Behavior and the Mortality Risk: Analysis of Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging from 2006 to 2014

- Socioeconomic Vulnerability, Mental Health, and Their Combined Effects on All-Cause Mortality in Koreans, over 45 Years: Analysis of Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging from 2006 to 2014

- Social Network, Social Support, Social Conflict and Mini-Mental State Examination Scores of Rural Older Adults : Differential Associations across Relationship Types

- Correlates of Social Engagement in Nursing Home Residents with Dementia