Korean Circ J.

2016 Jul;46(4):433-442. 10.4070/kcj.2016.46.4.433.

Women and Ischemic Heart Disease: Recognition, Diagnosis and Management

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Barbra Streisand Women's Heart Center, Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA. merz@cshs.org

- KMID: 2344417

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2016.46.4.433

Abstract

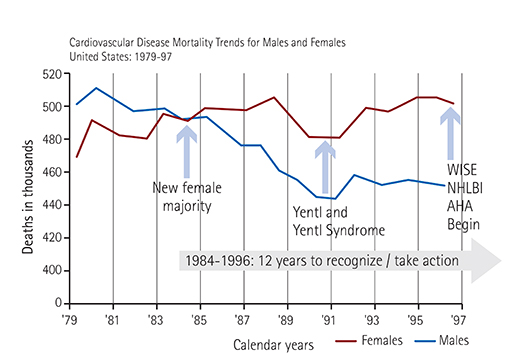

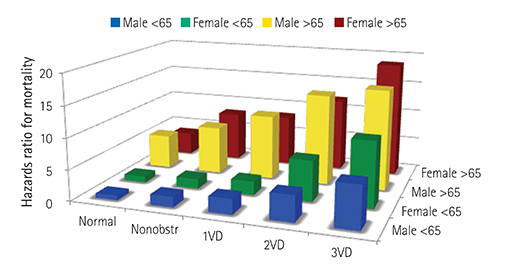

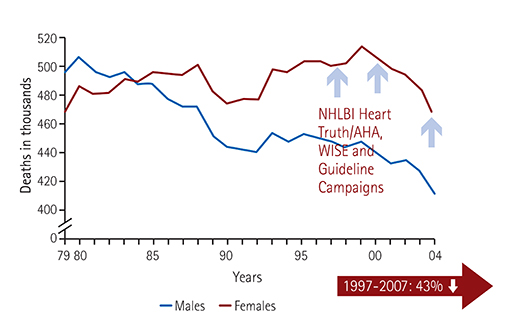

- Cardiovascular disease is one of the most frequent causes of death in both males and females throughout the world. However, women exhibit a greater symptom burden, more functional disability, and a higher prevalence of nonobstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) compared to men when evaluated for signs and symptoms of myocardial ischemia. This paradoxical sex difference appears to be linked to a sex-specific pathophysiology of myocardial ischemia including coronary microvascular dysfunction, a component of the 'Yentl Syndrome'. Accordingly, the term ischemic heart disease (IHD) is more appropriate for a discussion specific to women rather than CAD or coronary heart disease. Following the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Heart Truth/American Heart Association, Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation and guideline campaigns, the cardiovascular mortality in women has been decreased, although significant gender gaps in clinical outcomes still exist. Women less likely undergo testing, yet guidelines indicate that symptomatic women at intermediate to high IHD risk should have further test (e.g. exercise treadmill test or stress imaging) for myocardial ischemia and prognosis. Further, women have suboptimal use of evidence-based guideline therapies compared with men with and without obstructive CAD. Anti-anginal and anti-atherosclerotic strategies are effective for symptom and ischemia management in women with evidence of ischemia and nonobstructive CAD, although more female-specific study is needed. IHD guidelines are not "cardiac catheterization" based but related to evidence of "myocardial ischemia and angina". A simplified approach to IHD management with ABCs (aspirin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin-renin blockers, beta blockers, cholesterol management and statin) should be used and can help to increases adherence to guidelines.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Ford ES, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the U.S. from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling ofmortality rates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50:2128–2132.2. Dreyer RP, Wang Y, Strait KM, et al. Gender differences in the trajectory of recovery in health status among young patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the variation in recovery: role of gender on outcomes of young AMI patients (VIRGO) study. Circulation. 2015; 131:1971–1980.3. Proudfit WL, Shirey EK, Sones FM Jr. Selective cine coronary arteriography Correlation with clinical findings in 1,000 patients. Circulation. 1966; 33:901–910.4. Kemp HG, Kronmal RA, Vliestra RE, Frye RL. Seven year survival of patients with normal or near normal coronary arteriograms: a CASS registry study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986; 7:479–483.5. Sharaf BL, Pepine CJ, Kerensky RA, et al. Detailed angiographic analysis of women with suspected ischemic chest pain (pilot phase data from the NHLBI-sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation [WISE] Study Angiographic Core Laboratory). Am J Cardiol. 2001; 87:937–941. A36. Moriel M, Rozanski A, Klein J, Berman DS, Merz CN. The limited efficacy of exercise radionuclide ventriculography in assessing prognosis of women with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1995; 76:1030–1035.7. Bairey Merz CN, Shaw LJ, Reis SE, et al. Insights from the NHLBI-Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: Part II: gender differences in presentation, diagnosis, and outcome with regard to gender-based pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and macrovascular and microvascular coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 47:3 Suppl. S21–S29.8. Shaw LJ, Bairey Merz CN, Pepine CJ, et al. Insights from the NHLBI-Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: Part I: gender differences in traditional and novel risk factors, symptom evaluation, and gender-optimized diagnostic strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 47:3 Suppl. S4–S20.9. Shaw LJ, Shaw RE, Bairey Merz CN, et al. Impact of ethnicity and gender differences on angiographic coronary artery disease prevalence and in-hospital mortality in the American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Circulation. 2008; 117:1787–1801.10. Glaser R, Selzer F, Jacobs AK, et al. Effect of gender on prognosis following percutaneous coronary intervention for stable angina pectoris and acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2006; 98:1446–1450.11. Bugiardini R, Bairey Merz CN. Angina with "normal" coronary arteries: a changing philosophy. JAMA. 2005; 293:477–484.12. Smilowitz NR, Sampson BA, Abrecht CR, Siegfried JS, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR. Women have less severe and extensive coronary atherosclerosis in fatal cases of ischemic heart disease: an autopsy study. Am Heart J. 2011; 161:681–688.13. Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between women and men hospitalized for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:221–225.14. Steingart RM, Packer M, Hamm P, et al. Sex differences in the management of coronary artery disease. Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:226–230.15. Healy B. The Yentl syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:274–276.16. Johnston N, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Lagerqvist B. Are we using cardiovascular medications and coronary angiography appropriately in men and women with chest pain? Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:1331–1336.17. Merz CN. The Yentl syndrome is alive and well. Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:1313–1315.18. Lee DH, Jeong MH, Rhee JA, et al. Predictors of long-term survival in acute coronary syndrome patients with left ventricular dysfunction after percutaneous coronary intervention. Korean Circ J. 2012; 42:692–697.19. Merz CN, Kelsey SF, Pepine CJ, et al. The Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study: protocol design, methodology and feasibility report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999; 33:1453–1461.20. Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Pepine CJ, et al. Persistent chest pain predicts cardiovascular events in women without obstructive coronary artery disease: results from the NIH-NHLBI-sponsored Women's Ischaemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27:1408–1415.21. Reis SE, Holubkov R, Conrad Smith AJ, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is highly prevalent in women with chest pain in the absence of coronary artery disease: results from the NHLBI WISE study. Am Heart J. 2001; 141:735–741.22. Gulati M, Cooper-DeHoff RM, McClure C, et al. Adverse cardiovascular outcomes in women with nonobstructive coronary artery disease: a report from the Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation Study and the St James Women Take Heart Project. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:843–850.23. Kothawade K, Bairey Merz CN. Microvascular coronary dysfunction in women: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2011; 36:291–318.24. Sharaf B, Wood T, Shaw L, et al. Adverse outcomes among women presenting with signs and symptoms of ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease: findings from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) angiographic core laboratory. Am Heart J. 2013; 166:134–141.25. von Mering GO, Arant CB, Wessel TR. Abnormal coronary vasomotion as a prognostic indicator of cardiovascular events in women: results from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). Circulation. 2004; 109:722–725.26. Wong TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, et al. Retinal arteriolar narrowing and risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. JAMA. 2002; 287:1153–1159.27. Burke AP, Farb A, Malcolm GT, Liang Y, Smialek J, Virmani R. Effects of risk factors on the mechanism of acute thrombosis and sudden coronary death in women. Circulation. 1998; 97:2110–2116.28. Burke AP, Virmani R, Galis Z, Haudenschild CC, Muller JE. 34th Bethesda Conference: Task force #2--What is the pathologic basis for new atherosclerosis imaging techniques? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 41:1874–1886.29. Novack V, Cutlip DE, Jotkowitz A, Lieberman N, Porath A. Reduction in sex-based mortality difference with implementation of new cardiology guidelines. Am J Med. 2008; 121:597–603.30. Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2000; 21:1502–1513.31. McSweeney JC, Cody M, O'Sullivan P, Elberson K, Moser DK, Garvin BJ. Women's early warning symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003; 108:2619–2623.32. DeVon HA, Ryan CJ, Ochs AL, Shapiro M. Symptoms across the continuum of acute coronary syndromes: differences between women and men. Am J Crit Care. 2008; 17:14–24. quiz 25.33. Johnson BD, Kelsey SF, Bairey Merz CN. Chapter 10. Clinical risk assessment in women: chest discomfort. Report from the WISE study. In : Shaw LJ, Redberg RF, editors. Coronary Disease in Women: Evidence-Based Diagnosis and Treatment. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press;2003. p. 129–141.34. Mieres JH, Shaw LJ, Arai A, et al. Role of noninvasive testing in the clinical evaluation of women with suspected coronary artery disease: Consensus statement from the Cardiac Imaging Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and the Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2005; 111:682–696.35. Mieres JH, Gulati M, Bairey Merz N, et al. Role of noninvasive testing in the clinical evaluation of women with suspected ischemic heart disease: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014; 130:350–379.36. Alexander KP, Shaw LJ, Shaw LK, Delong ER, Mark DB, Peterson ED. Value of exercise treadmill testing in women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998; 32:1657–1664.37. Shaw LJ, Mieres JH, Hendel RH, et al. Comparative effectiveness of exercise electrocardiography with or without myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography in women with suspected coronary artery disease: results from the What Is the Optimal Method for Ischemia Evaluation in Women (WOMEN) trial. Circulation. 2011; 124:1239–1249.38. Mieres JH, Shaw LJ, Arai A, et al. Role of noninvasive testing in the clinical evaluation of women with suspected coronary artery disease: consensus statement from the Cardiac Imaging Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and the Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2005; 111:682–696.39. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60:e44–e164.40. Shaw LJ, Vasey C, Sawada S, Rimmerman C, Marwick TH. Impact of gender on risk stratification by exercise and dobutamine stress echocardiography: long-term mortality in 4234 women and 6898 men. Eur Heart J. 2005; 26:447–456.41. Arruda-Olson AM, Juracan EM, Mahoney DW, McCully RB, Roger VL, Pellikka PA. Prognostic value of exercise echocardiography in 5,798 patients: is there a gender difference. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002; 39:625–631.42. Shaw LJ, Hage FG, Berman DS, Hachamovitch R, Iskandrian A. Prognosis in the era of comparative effectiveness research: where is nuclear cardiology now and where should it be? J Nucl Cardiol. 2012; 19:1026–1043.43. Gargiulo P, Petretta M, Bruzzese D, et al. Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy and echocardiography for detecting coronary artery disease in hypertensive patients: a meta-analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011; 38:2040–2049.44. Bateman TM, Heller GV, McGhie AI, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of rest/stress ECG-gated Rb-82 myocardial perfusion PET: comparison with ECG-gated Tc-99m sestamibi SPECT. J Nucl Cardiol. 2006; 13:24–33.45. Kay J, Dorbala S, Goyal A, et al. Influence of sex on risk stratification with stress myocardial perfusion Rb-82 positron emission tomography: results from the PET (Positron Emission Tomography) Prognosis Multicenter Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62:1866–1876.46. Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, et al. Age- and sex-related differences in all-cause mortality risk based on coronary computed tomography angiography findings results from the International Multicenter CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter Registry) of 23,854 patients without known coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:849–860.47. Lin FY, Shaw LJ, Dunning AM, et al. Mortality risk in symptomatic patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease: a prospective 2-center study of 2,583 patients undergoing 64-detector row coronary computed tomographic angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:510–519.48. Pepine CJ, Anderson RD, Sharaf BL, et al. Coronary microvascular reactivity to adenosine predicts adverse outcome in women evaluated for suspected ischemia results from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute WISE (Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55:2825–2832.49. Chandra NC, Ziegelstein RC, Rogers WJ, et al. Observations of the treatment of women in the United States with myocardial infarction: a report from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction-I. Arch Intern Med. 1998; 158:981–988.50. Nohria A, Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM. Gender differences in mortality after myocardial infarction. Why women fare worse than men. Cardiol Clin. 1998; 16:45–57.51. Scott LB, Allen JK. Providers' perceptions of factors affecting women's referral to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation programs: an exploratory study. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2004; 24:387–391.52. O'Meara JG, Kardia SL, Armon JJ, Brown CA, Boerwinkle E, Turner ST. Ethnic and sex differences in the prevalence, treatment, and control of dyslipidemia among hypertensive adults in the GENOA study. Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164:1313–1318.53. Hendrix KH, Riehle JE, Egan BM. Ethnic, gender, and age-related differences in treatment and control of dyslipidemia in hypertensive patients. Ethn Dis. 2005; 15:11–16.54. Cho L, Hoogwerf B, Huang J, Brennan DM, Hazen SL. Gender differences in utilization of effective cardiovascular secondary prevention: a Cleveland clinic prevention database study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008; 17:515–521.55. Chou AF, Scholle SH, Weisman CS, Bierman AS, Correa-de-Araujo R, Mosca L. Gender disparities in the quality of cardiovascular disease care in private managed care plans. Womens Health Issues. 2007; 17:120–130.56. Reis SE, Holubkov R, Lee JS, et al. Coronary flow velocity response to adenosine characterizes coronary microvascular function in women with chest pain and no obstructive coronary disease. Results from the pilot phase of the Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999; 33:1469–1475.57. Wessel TR, Arant CB, McGorray SP, et al. Coronary microvascular reactivity is only partially predicted by atherosclerosis risk factors or coronary artery disease in women evaluated for suspected ischemia: results from the NHLBI Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). Clin Cardiol. 2007; 30:69–74.58. LaBresh KA, Fonarow G, Ellrodt AG, et al. Get with the guidelines improves cardiovascular care in hospitalized patients with CAD. Circulation. 2003; 108:Suppl 4. 722. (Abstract).59. Lanza GA, Colonna G, Pasceri V, Maseri A. Atenolol versus amlodipine versus isosorbide-5-mononitrate on anginal symptoms in syndrome X. Am J Cardiol. 1999; 84:854–856. A860. Pizzi C, Manfrini O, Fontana F, Bugiardini R. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase in cardiac Syndrome X: role of superoxide dismutase activity. Circulation. 2004; 109:53–58.61. Kayikcioglu M, Payzin S, Yavuzgil O, Kultursay H, Can LH, Soydan I. Benefits of statin treatment in cardiac syndrome-X1. Eur Heart J. 2003; 24:1999–2005.62. Chen JW, Hsu NW, Wu TC, Lin SJ, Chang MS. Long-term angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition reduces plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine and improves endothelial nitric oxide bioavailability and coronary microvascular function in patients with syndrome X. Am J Cardiol. 2002; 90:974–982.63. Manfrini O, Pizzi C, Morgagni G, Fontana F, Bugiardini R. Effects of pravastatin on myocardial perfusion after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 2004; 93:1391–1393. A664. Eriksson BE, Tyni-Lennè R, Svedenhag J, et al. Physical training in Syndrome X: physical training counteracts deconditioning and pain in Syndrome X. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 36:1619–1625.65. Alexander KP, Chen AY, Newby LK, et al. Sex differences in major bleeding with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: results from the CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) initiative. Circulation. 2006; 114:1380–1387.66. Ambrosioni E, Borghi C, Magnani B. The effect of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor zofenopril on mortality and morbidity after anterior myocardial infarction. The Survival of Myocardial Infarction Long-Term Evaluation (SMILE) Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1995; 332:80–85.67. Hjalmarson A, Elmfeldt D, Herlitz J, et al. Effect on mortality of metoprolol in acute myocardial infarction. A double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 1981; 2:823–827.68. Gluckman TJ, Sachdev M, Schulman SP, Blumenthal RS. A simplified approach to the management of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2005; 293:349–357.69. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014; 130:e344–e426.70. Timmis AD, Chaitman BR, Crager M. Effects of ranolazine on exercise tolerance and HbA1c in patients with chronic angina and diabetes. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27:42–48.71. Chaitman BR, Pepine CJ, Parker JO, et al. Effects of ranolazine with atenolol, amlodipine, or diltiazem on exercise tolerance and angina frequency in patients with severe chronic angina: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004; 291:309–316.72. Chaitman BR, Skettino SL, Parker JO, et al. Anti-ischemic effects and long-term survival during ranolazine monotherapy in patients with chronic severe angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004; 43:1375–1382.73. Belardinelli L, Shryock JC, Fraser H. Inhibition of the late sodium current as a potential cardioprotective principle: effects of the late sodium current inhibitor ranolazine. Heart. 2006; 92:Suppl 4. iv6–iv14.74. Hochman JS, Tamis JE, Thompson TD, et al. Sex, clinical presentation, and outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341:226–232.75. Glaser R, Herrmann HC, Murphy SA, et al. Benefit of an early invasive management strategy in women with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2002; 288:3124–3129.76. Diver DJ, Bier JD, Ferreira PE, et al. Clinical and arteriographic characterization of patients with unstable angina without critical coronary arterial narrowing (from the TIMI-IIIA Trial). Am J Cardiol. 1994; 74:531–537.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Cardiovascular Disease in Women

- Role of Echocardiography in the Management of Cardiac Disease in Women

- Implications of Managing Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Cardiovascular Diseases

- Trends in Ischemic Heart Disease Mortality in Korea, 1985-2009: An Age-period-cohort Analysis

- A Clinical Observation on 24 Hour Holter Monitoring: The Differences between Day and Night Time