J Korean Soc Med Inform.

2009 Jun;15(2):191-199. 10.4258/jksmi.2009.15.2.191.

A Data Warehouse Based Retrospective Post-marketing Surveillance Method: A Feasibility Test with Fluoxetine

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Medical Informatics, Ajou University School of Medicine, Korea. veritas@ajou.ac.kr

- 2Department of Medicine and Science, Gacheon University School of Medicine, Korea.

- 3Division of Bio-Medical Informatics, Center for Genome Science, National Institute of Health, KCDC, Korea.

- KMID: 2211388

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4258/jksmi.2009.15.2.191

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

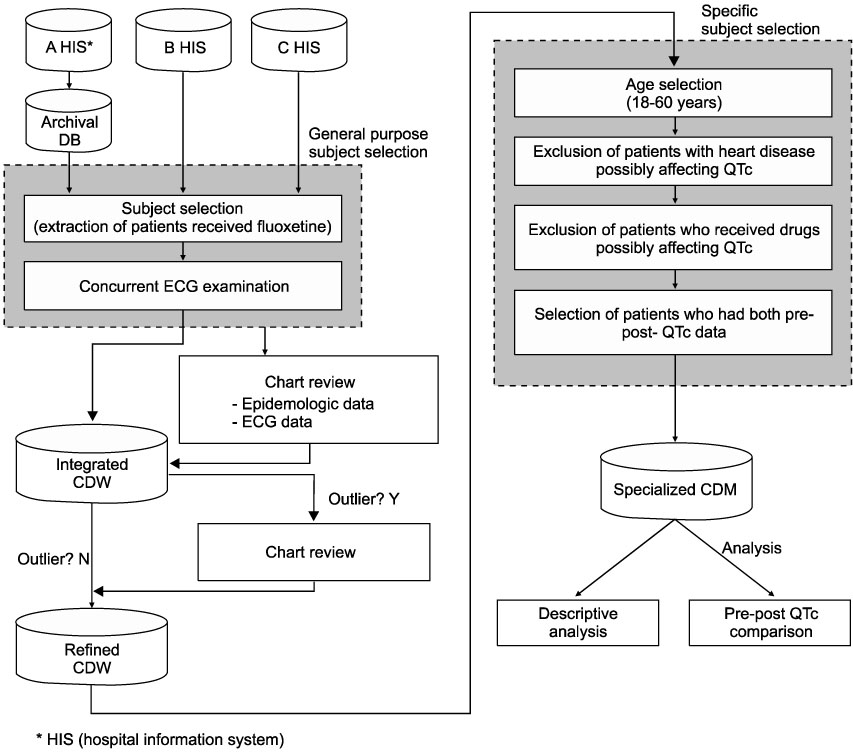

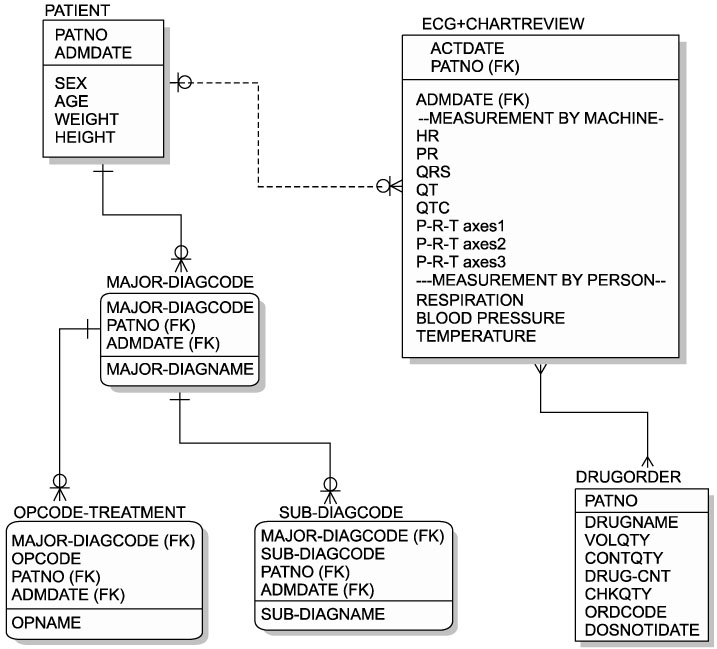

Post-marketing surveillance (PMS) is an adverse events monitoring practice of pharmaceutical drugs on the market. Traditional PMS methods are labor intensive and expensive to perform, because they are largely based on manual work including phone-calling, mailing, or direct visits to relevant subjects. The objective of this study was to develop and validate a PMS methodology based on the clinical data warehouse (CDW). METHODS: We constructed a archival DB using a hospital information system and a refined CDW from three different hospitals. Fluoxetine hydrochloride, an antidepressant, was selected as the target monitoring drug. Corrected QT prolongation on ECG was selected as the target adverse outcome. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed to analyze the difference in the corrected QT interval before and after the target drug administration. RESULTS: A refined CDW was successfully constructed from three different hospitals. Table specifications and an entity-relation diagram were developed and are presented. A total of 13 subjects were selected for monitoring. There was no statistically significant difference in the QT interval before and after target drug administration (p=0.727). CONCLUSION: The PMS method based on CDW was successfully performed on the target drug. This IT-based alternative surveillance method might be beneficial in the PMS environment of the future.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Analysis of Relationship between Levofloxacin and Corrected QT Prolongation Using a Clinical Data Warehouse

Man Young Park, Eun Yeob Kim, Young Ho Lee, Woojae Kim, Ku Sang Kim, Seung Soo Sheen, Hong Seok Lim, Rae Woong Park

Healthc Inform Res. 2011;17(1):58-66. doi: 10.4258/hir.2011.17.1.58.

Reference

-

1. Brewer T, Colditz GA. Postmarketing surveillance and adverse drug reactions: current perspectives and future needs. JAMA. 1999. 281(9):824–829.

Article2. Yang Q, Khoury MJ, James LM, Olney RS, Paulozzi LJ, Erickson JD. The return of thalidomide: are birth defects surveillance systems ready? Am J Med Genet. 1997. 73(3):251–258.

Article3. Swanson G, Ward A. Recruiting clinical trials: toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995. 87(23):1747–1759.4. Ahmad S. Adverse drug event monitoring at the food and drug administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2003. 18(1):57–60.

Article5. Waller PC, Coulson RA, Wood SM. Regulatory pharmacovigilance in the United Kingdom: current principles and practice. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1996. 5(6):363–375.

Article6. Weaver J, Bonnel RA, Karwoski CB, Brinker AD, Beitz J. GI events leading to death in association with celecoxib and rofecoxib. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001. 96(12):3449–3450.

Article7. Wysowski DK, Bacsanyi J. Cisapride and fatal arrhythmia. N Engl J Med. 1996. 335(4):290–291.

Article8. Wysowski DK, Corken A, Gallo-Torres H, Talarico L, Rodriguez EM. Postmarketing reports of QT prolongation and ventricular arrhythmia in association with cisapride and Food and Drug Administration regulatory actions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001. 96(6):1698–1703.

Article9. Brown AM. Drugs, hERG and sudden death. Cell Calcium. 2004. 35(6):543–547.

Article10. Fermini B, Fossa AA. The impact of drug-induced QT interval prolongation on drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003. 2(6):439–447.

Article11. Lasser KE, Allen PD, Woolhandler SJ, Himmelstein DU, Wolfe SM, Bor DH. Timing of new black box warnings and withdrawals for prescription medications. JAMA. 2002. 287(17):2215–2220.

Article12. Arfken CL, Cicero TJ. Postmarketing surveillance for drug abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003. 70:3 Suppl. S97–S105.

Article13. Guth BD, Germeyer S, Kolb W, Markert M. Developing a strategy for the nonclinical assessment of proarrhythmic risk of pharmaceuticals due to prolonged ventricular repolarization. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2004. 49(3):159–169.

Article14. Viskin S. Long QT syndromes and torsade de pointes. Lancet. 1999. 354(9190):1625–1633.

Article15. Simon SR, Kaushal R, Cleary PD, Jenter CA, Volk LA, Orav EJ, et al. Physicians and electronic health records: a statewide survey. Arch Intern Med. 2007. 167(5):507–512.16. Menachemi N, Perkins RM, van Durme DJ, Brooks RG. Examining the adoption of electronic health records and personal digital assistants by family physicians in Florida. Inform Prim Care. 2006. 14(1):1–9.

Article17. Sittig F, Guappone K, Campbell E, Dykstra R, Ash J. A survey of USA acute care hospitals' computer-based provider order entry system infusion levels. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007. 129(1):252.18. Park RW, Shin SS, Choi YI, Ahn JO, Hwang SC. Computerized physician order entry and electronic medical record systems in Korean teaching and general hospitals: results of a 2004 survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005. 12(6):642–647.

Article19. DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Rao SR, Donelan K, Ferris TG, Jha A, et al. Electronic health records in ambulatory care--a national survey of physicians. N Engl J Med. 2008. 359(1):50–60.

Article20. Dewitt JG, Hampton PM. Development of a data warehouse at an academic health system: knowing a place for the first time. Acad Med. 2005. 80(11):1019–1025.

Article21. Schubart JR, Einbinder JS. Evaluation of a data warehouse in an academic health sciences center. Int J Med Inform. 2000. 60(3):319–333.

Article22. Silver M, Sakata T, Su HC, Herman C, Dolins SB, O'Shea MJ. Case study: how to apply data mining techniques in a healthcare data warehouse. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2001. 15(2):155–164.23. Zhang Q, Matsumura Y, Teratani T, Yoshimoto S, Mineno T, Nakagawa K, et al. The application of an institutional clinical data warehouse to the assessment of adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Evaluation of aminoglycoside and cephalosporin associated nephrotoxicity. Methods Inf Med. 2007. 46(5):516–522.

Article24. Hauben M, Patadia V, Gerrits C, Walsh L, Reich L. Data mining in pharmacovigilance: the need for a balanced perspective. Drug Saf. 2005. 28(10):835–842.25. Waller PC, Evans SJ. A model for the future conduct of pharmacovigilance. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2003. 12(1):17–29.

Article26. Szirbik NB, Pelletier C, Chaussalet T. Six methodological steps to build medical data warehouses for research. Int J Med Inform. 2006. 75(9):683–691.

Article27. Hinrichsen VL, Kruskal B, O'Brien MA, Lieu TA, Platt R. Using electronic medical records to enhance detection and reporting of vaccine adverse events. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007. 14(6):731–735.

Article28. Sheen SS, Choi JE, Park RW, Kim EY, Lee YH, Kang UG. Overdose rate of drugs requiring renal dose adjustment: data analysis of 4 years prescriptions at a tertiary teaching hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2008. 23(4):423–428.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Problems within the post-marketing surveillance system in Korea: Time for a change

- The Current Status of the Organizations Dedicated to Post-marketing Safety Management of Pharmaceuticals

- Case Analysis in Drug Approval by FDA/EMA Using Real-World Data/Real-World Evidence

- Analysis of Relationship between Levofloxacin and Corrected QT Prolongation Using a Clinical Data Warehouse

- The Analysis of Clinical Information by Building the Clinical Data Warehouse