J Gynecol Oncol.

2013 Oct;24(4):342-351. 10.3802/jgo.2013.24.4.342.

Trends in incidence and survival outcome of epithelial ovarian cancer: 30-year national population-based registry in Taiwan

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan. wenfangcheng@yahoo.com

- 2Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan.

- 3Graduate Institute of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, National Taiwan University College of Public Health, Taipei, Taiwan.

- 4Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taipei, Taiwan.

- 5Department of Pathology, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan.

- 6Institute of Life Sciences, School of Public Health, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, Taiwan. yousl1990@ntu.edu.tw

- 7Genomics Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan.

- 8Graduate Institute of Oncology, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan.

- KMID: 2177876

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2013.24.4.342

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To investigate the changes of incidence and prognosis of epithelial ovarian cancer in thirty years in Taiwan.

METHODS

The databases of women with epithelial ovarian cancer during the period from 1979 to 2008 were retrieved from the National Cancer Registration System of Taiwan. The incidence and prognosis of these patients were analyzed.

RESULTS

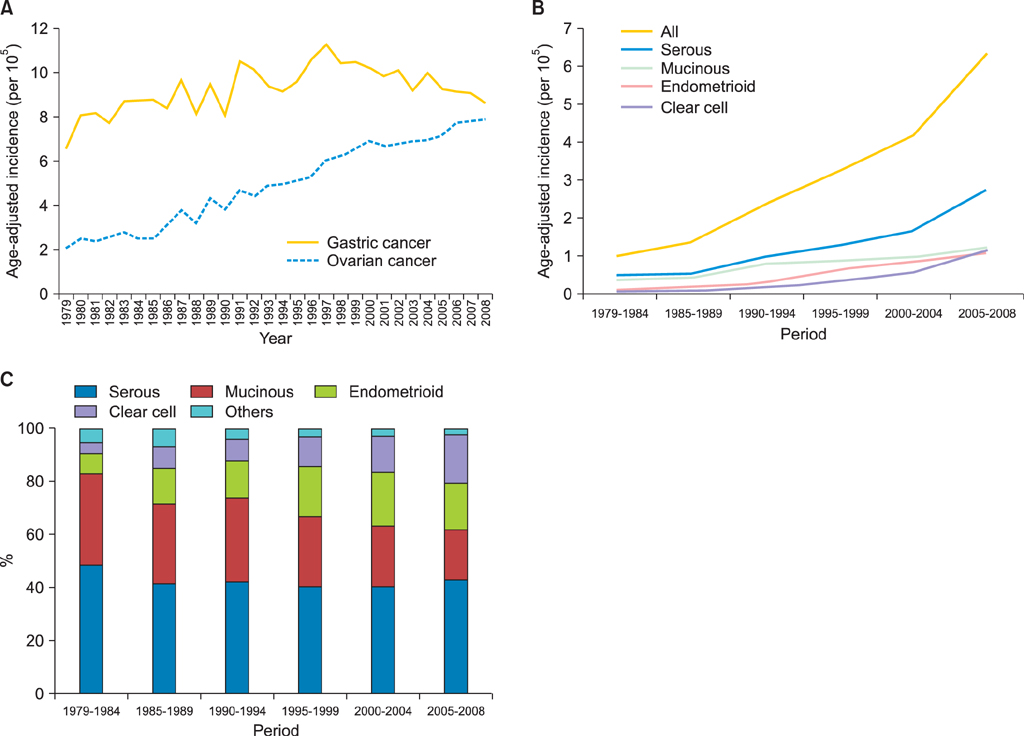

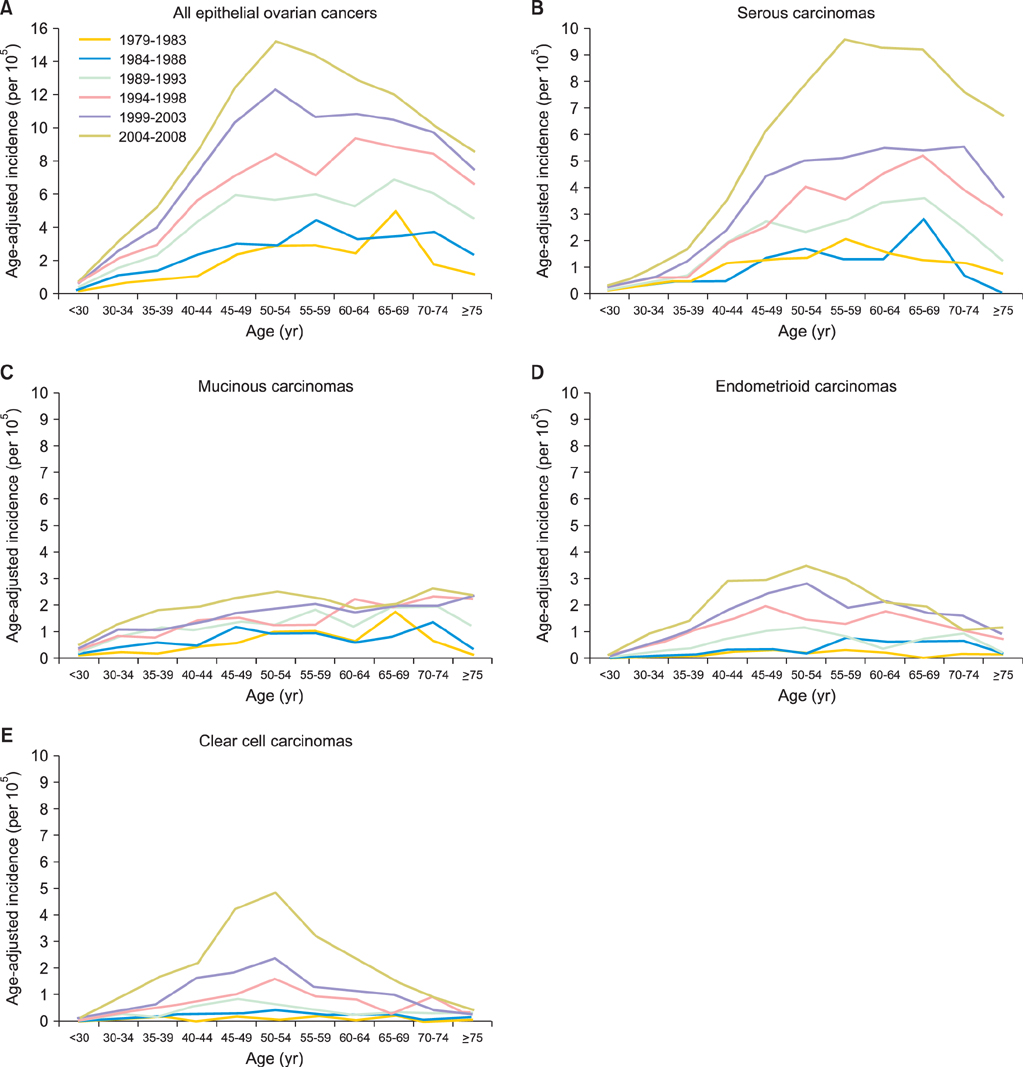

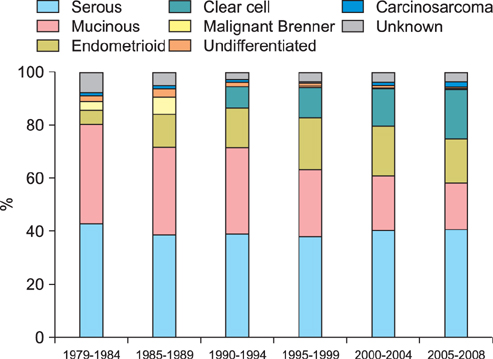

Totally 9,491 patients were included in the study. The age-adjusted incidences of epithelial ovarian cancer were 1.01, 1.37, 2.37, 3.24, 4.18, and 6.33 per 100,000 person-years, respectively, in every 5-year period from 1979 to 2008. The age-specific incidence rates increased especially in serous, endometrioid and clear cell carcinoma, and the age of diagnosis decreased from sixty to fifty years old in the three decades. Patients with mucinous, endometrioid, or clear cell carcinoma had better long-term survival than patients with serous carcinoma (log rank test, p<0.001). Patients with undifferentiated carcinoma or carcinosarcoma had poorer survival than those with serous carcinoma (log rank test, p<0.001). The mortality risk of age at diagnosis of 30-39 was significantly higher than that of age of 70 years or more (test for trend, p<0.001). The mortality risk decreased from the period of 1996-1999 (hazard ratio [HR], 0.90; p=0.054) to the period after 2000 (HR, 0.74; p<0.001) as compared with that from the period of 1991-1995.

CONCLUSION

An increasing incidence and decreasing age of diagnosis in epithelial ovarian cancer patients were noted. Histological type, age of diagnosis, and treatment period were important prognostic factors for epithelial ovarian carcinoma.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Survival benefit of patients with early-stage ovarian carcinoma treated with paclitaxel chemotherapeutic regimens

Chien-An Chen, Chun-Ju Chiang, Yun-Yuan Chen, San-Lin You, Shu-Feng Hsieh, Chao-Hsiun Tang, Wen-Fang Cheng

J Gynecol Oncol. 2018;29(1):. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e16.Prior uterine myoma and risk of ovarian cancer: a population-based case-control study

Jenn-Jhy Tseng, Chun-Che Huang, Hsiu-Yin Chiang, Yi-Huei Chen, Ching-Heng Lin

J Gynecol Oncol. 2019;30(5):. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2019.30.e72.

Reference

-

1. Huang YW, Kuo CT, Stoner K, Huang TH, Wang LS. An overview of epigenetics and chemoprevention. FEBS Lett. 2011; 585:2129–2136.2. Agarwal R, Kaye SB. Ovarian cancer: strategies for overcoming resistance to chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003; 3:502–516.3. Kurman RJ, Shih IeM. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: a proposed unifying theory. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010; 34:433–443.4. International Agency for Research on Cancer. CI5plus: cancer incidence in five continents annual dataset [Internet]. Cedex: International Agency for Research on Cancer;cited 2013 Aug 20. Available from: http://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5plus/ci5plus.htm.5. Chan JK, Cheung MK, Husain A, Teng NN, West D, Whittemore AS, et al. Patterns and progress in ovarian cancer over 14 years. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 108(3 Pt 1):521–528.6. Cabanes A, Vidal E, Perez-Gomez B, Aragones N, Lopez-Abente G, Pollan M. Age-specific breast, uterine and ovarian cancer mortality trends in Spain: changes from 1980 to 2006. Cancer Epidemiol. 2009; 33:169–175.7. Bray F, Loos AH, Tognazzo S, La Vecchia C. Ovarian cancer in Europe: Cross-sectional trends in incidence and mortality in 28 countries, 1953-2000. Int J Cancer. 2005; 113:977–990.8. Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Schwartz AG, Qureshi F, Jacques S, Malone J, Munkarah AR. Ovarian cancer: changes in patterns at diagnosis and relative survival over the last three decades. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 189:1120–1127.9. Gonzalez-Diego P, Lopez-Abente G, Pollan M, Ruiz M. Time trends in ovarian cancer mortality in Europe (1955-1993): effect of age, birth cohort and period of death. Eur J Cancer. 2000; 36:1816–1824.10. Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare. National Cancer Registry [Internet]. cited 2013 Aug 20. Available from: http://www.bhp.doh.gov.tw/BHPNET/Portal/StatisticsShow.aspx?No=200911300001.11. Chiang CJ, Chen YC, Chen CJ, You SL, Lai MS. Taiwan Cancer Registry Task Force. Cancer trends in Taiwan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010; 40:897–904.12. Tavassoeli FA. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and female genital organs. Lyon: IARC press;2003.13. Leen SL, Singh N. Pathology of primary and metastatic mucinous ovarian neoplasms. J Clin Pathol. 2012; 65:591–595.14. McCluggage WG. Immunohistochemistry in the distinction between primary and metastatic ovarian mucinous neoplasms. J Clin Pathol. 2012; 65:596–600.15. Young RH. From Krukenberg to today: the ever present problems posed by metastatic tumors in the ovary. Part II. Adv Anat Pathol. 2007; 14:149–177.16. Seidman JD, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM. Primary and metastatic mucinous adenocarcinomas in the ovaries: incidence in routine practice with a new approach to improve intraoperative diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003; 27:985–993.17. Hart WR. Mucinous tumors of the ovary: a review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2005; 24:4–25.18. Chornokur G, Amankwah EK, Schildkraut JM, Phelan CM. Global ovarian cancer health disparities. Gynecol Oncol. 2013; 129:258–264.19. Hunn J, Rodriguez GC. Ovarian cancer: etiology, risk factors, and epidemiology. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 55:3–23.20. Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies of Ovarian Cancer. Beral V, Doll R, Hermon C, Peto R, Reeves G. Ovarian cancer and oral contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of data from 45 epidemiological studies including 23,257 women with ovarian cancer and 87,303 controls. Lancet. 2008; 371:303–314.21. Chow LP, Nair NK. Oral contraceptive use and diseases of the circulatory system in Taiwan: an analysis of mortality statistics. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1980; 18:420–432.22. Wang TM, Liu Y. Re-examination of Taiwan's total fertility rate: an application of the ACF method. J Popul Stud. 2008; 36:37–65.23. Lin YC, Yen LL, Chen SY, Kao MD, Tzeng MS, Huang PC, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity and its associated factors: findings from National Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan, 1993-1996. Prev Med. 2003; 37:233–241.24. Lin CH, Chen YC, Chiang CJ, Lu YS, Kuo KT, Huang CS, et al. The emerging epidemic of estrogen-related cancers in young women in a developing Asian country. Int J Cancer. 2012; 130:2629–2637.25. Nagle CM, Olsen CM, Webb PM, Jordan SJ, Whiteman DC, Green AC, et al. Endometrioid and clear cell ovarian cancers: a comparative analysis of risk factors. Eur J Cancer. 2008; 44:2477–2484.26. Vlahos NF, Kalampokas T, Fotiou S. Endometriosis and ovarian cancer: a review. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010; 26:213–219.27. Fang GC, Wu YS, Fu PP, Yang IL, Chen MH. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the ambient air of suburban and industrial regions of central Taiwan. Chemosphere. 2004; 54:443–452.28. Chen CY, Wen TY, Wang GS, Cheng HW, Lin YH, Lien GW. Determining estrogenic steroids in Taipei waters and removal in drinking water treatment using high-flow solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Sci Total Environ. 2007; 378:352–365.29. Chen ML, Chen JS, Tang CL, Mao IF. The internal exposure of Taiwanese to phthalate--an evidence of intensive use of plastic materials. Environ Int. 2008; 34:79–85.30. Winter WE 3rd, Maxwell GL, Tian C, Carlson JW, Ozols RF, Rose PG, et al. Prognostic factors for stage III epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:3621–3627.31. Ioka A, Tsukuma H, Ajiki W, Oshima A. Ovarian cancer incidence and survival by histologic type in Osaka, Japan. Cancer Sci. 2003; 94:292–296.32. Chan JK, Urban R, Cheung MK, Osann K, Shin JY, Husain A, et al. Ovarian cancer in younger vs older women: a population-based analysis. Br J Cancer. 2006; 95:1314–1320.33. Gatta G, Capocaccia R, De Angelis R, Stiller C, Coebergh JW. EUROCARE Working Group. Cancer survival in European adolescents and young adults. Eur J Cancer. 2003; 39:2600–2610.34. Chan JK, Loizzi V, Lin YG, Osann K, Brewster WR, DiSaia PJ. Stages III and IV invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma in younger versus older women: what prognostic factors are important? Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 102:156–161.35. Kosary CL. FIGO stage, histology, histologic grade, age and race as prognostic factors in determining survival for cancers of the female gynecological system: an analysis of 1973-87 SEER cases of cancers of the endometrium, cervix, ovary, vulva, and vagina. Semin Surg Oncol. 1994; 10:31–46.36. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009; 59:225–249.37. Hirabayashi Y, Marugame T. Comparison of time trends in ovary cancer mortality (1990-2006) in the world, from the WHO Mortality Database. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009; 39:860–861.38. Fader AN, Rose PG. Role of surgery in ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:2873–2883.39. Wakabayashi MT, Lin PS, Hakim AA. The role of cytoreductive/debulking surgery in ovarian cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008; 6:803–810.40. Tan W, Stehman FB, Carter RL. Mortality rates due to gynecologic cancers in New York state by demographic factors and proximity to a Gynecologic Oncology Group member treatment center: 1979-2001. Gynecol Oncol. 2009; 114:346–352.41. Chan JK, Sherman AE, Kapp DS, Zhang R, Osann KE, Maxwell L, et al. Influence of gynecologic oncologists on the survival of patients with endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29:832–838.42. Stewart SL, Rim SH, Richards TB. Gynecologic oncologists and ovarian cancer treatment: avenues for improved survival. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011; 20:1257–1260.43. Taiwan Association of Gynecologic Oncologists. TAGO [Internet]. Taiwan: TAGO;cited 2013 Aug 20. Available from: http://www.tago.org.tw/eng/about.asp.44. McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, Kucera PR, Partridge EE, Look KY, et al. Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996; 334:1–6.45. Muggia FM, Braly PS, Brady MF, Sutton G, Niemann TH, Lentz SL, et al. Phase III randomized study of cisplatin versus paclitaxel versus cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with suboptimal stage III or IV ovarian cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2000; 18:106–115.46. du Bois A, Luck HJ, Meier W, Adams HP, Mobus V, Costa S, et al. A randomized clinical trial of cisplatin/paclitaxel versus carboplatin/paclitaxel as first-line treatment of ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003; 95:1320–1329.47. Kumar S, Mahdi H, Bryant C, Shah JP, Garg G, Munkarah A. Clinical trials and progress with paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. Int J Womens Health. 2010; 2:411–427.48. Piccart MJ, Bertelsen K, James K, Cassidy J, Mangioni C, Simonsen E, et al. Randomized intergroup trial of cisplatin-paclitaxel versus cisplatin-cyclophosphamide in women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: three-year results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000; 92:699–708.49. International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm Group. Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus standard chemotherapy with either single-agent carboplatin or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in women with ovarian cancer: the ICON3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2002; 360:505–515.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Annual report of gynecologic cancer registry program in Korea: 1991~2004

- The incidence and survival of cervical, ovarian, and endometrial cancer in Korea, 1999-2017: Korea Central Cancer Registry

- Second Primary Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancers after Breast Cancer Diagnosis: Korea Central Cancer Registry

- Incidence trends for epithelial peritoneal, ovarian, and fallopian tube cancer during 1999–2016: a retrospective study based on the Korean National Cancer Incidence Database

- Korean Brain Tumor registry (II): Registry and Data Base formula