Blood Res.

2013 Jun;48(2):76-86. 10.5045/br.2013.48.2.76.

Cardiovascular repair with bone marrow-derived cells

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, GA, USA. yyoon5@emory.edu

- KMID: 2172905

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5045/br.2013.48.2.76

Abstract

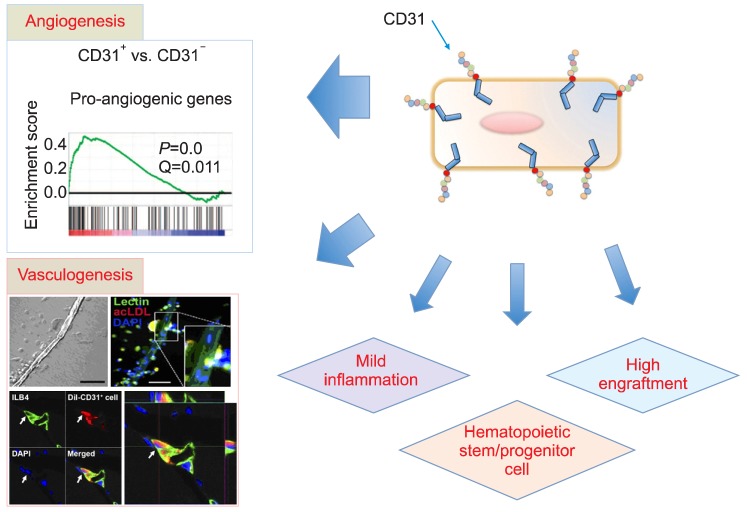

- While bone marrow (BM)-derived cells have been comprehensively studied for their propitious pre-clinical results, clinical trials have shown controversial outcomes. Unlike previously acknowledged, more recent studies have now confirmed that humoral and paracrine effects are the key mechanisms for tissue regeneration and functional recovery, instead of transdifferentiation of BM-derived cells into cardiovascular tissues. The progression of the understanding of BM-derived cells has further led to exploring efficient methods to isolate and obtain, without mobilization, sufficient number of cell populations that would eventually have a higher therapeutic potential. As such, hematopoietic CD31+ cells, prevalent in both bone marrow and peripheral blood, have been discovered, in recent studies, to have angiogenic and vasculogenic activities and to show strong potential for therapeutic neovascularization in ischemic tissues. This article will discuss recent advancement on BM-derived cell therapy and the implication of newly discovered CD31+ cells.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011; 123:e18–e209. PMID: 21160056.2. Feinglass J, Sohn MW, Rodriguez H, Martin GJ, Pearce WH. Perioperative outcomes and amputation-free survival after lower extremity bypass surgery in California hospitals, 1996-1999, with follow-up through 2004. J Vasc Surg. 2009; 50:776–783.e1. PMID: 19595538.

Article3. Taylor SM, Kalbaugh CA, Blackhurst DW, Kellicut DC, Langan EM 3rd, Youkey JR. A comparison of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty versus amputation for critical limb ischemia in patients unsuitable for open surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2007; 45:304–310. PMID: 17264008.

Article4. Fang J, Mensah GA, Croft JB, Keenan NL. Heart failure-related hospitalization in the U.S., 1979 to 2004. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 52:428–434. PMID: 18672162.

Article5. Bifari F, Pacelli L, Krampera M. Immunological properties of embryonic and adult stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2010; 2:50–60. PMID: 21607122.

Article6. Cao F, Lin S, Xie X, et al. In vivo visualization of embryonic stem cell survival, proliferation, and migration after cardiac delivery. Circulation. 2006; 113:1005–1014. PMID: 16476845.

Article7. Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007; 131:861–872. PMID: 18035408.

Article8. Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006; 126:663–676. PMID: 16904174.

Article9. Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003; 302:415–419. PMID: 14564000.10. Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010; 467:285–290. PMID: 20644535.

Article11. Polo JM, Liu S, Figueroa ME, et al. Cell type of origin influences the molecular and functional properties of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2010; 28:848–855. PMID: 20644536.

Article12. Dhodapkar KM, Feldman D, Matthews P, et al. Natural immunity to pluripotency antigen OCT4 in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107:8718–8723. PMID: 20404147.

Article13. Zhao T, Zhang ZN, Rong Z, Xu Y. Immunogenicity of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011; 474:212–215. PMID: 21572395.

Article14. Kalka C, Masuda H, Takahashi T, et al. Transplantation of ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cells for therapeutic neovascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000; 97:3422–3427. PMID: 10725398.

Article15. Murohara T, Ikeda H, Duan J, et al. Transplanted cord blood-derived endothelial precursor cells augment postnatal neovascularization. J Clin Invest. 2000; 105:1527–1536. PMID: 10841511.

Article16. Kawamoto A, Gwon HC, Iwaguro H, et al. Therapeutic potential of ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cells for myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2001; 103:634–637. PMID: 11156872.

Article17. Kawamoto A, Iwasaki H, Kusano K, et al. CD34-positive cells exhibit increased potency and safety for therapeutic neovascularization after myocardial infarction compared with total mononuclear cells. Circulation. 2006; 114:2163–2169. PMID: 17075009.

Article18. Jeong JO, Kim MO, Kim H, et al. Dual angiogenic and neurotrophic effects of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells on diabetic neuropathy. Circulation. 2009; 119:699–708. PMID: 19171856.

Article19. Schatteman GC, Hanlon HD, Jiao C, Dodds SG, Christy BA. Blood-derived angioblasts accelerate blood-flow restoration in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest. 2000; 106:571–578. PMID: 10953032.

Article20. Kocher AA, Schuster MD, Szabolcs MJ, et al. Neovascularization of ischemic myocardium by human bone-marrow-derived angioblasts prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis, reduces remodeling and improves cardiac function. Nat Med. 2001; 7:430–436. PMID: 11283669.

Article21. Iwasaki H, Kawamoto A, Ishikawa M, et al. Dose-dependent contribution of CD34-positive cell transplantation to concurrent vasculogenesis and cardiomyogenesis for functional regenerative recovery after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2006; 113:1311–1325. PMID: 16534028.

Article22. Bartunek J, Vanderheyden M, Vandekerckhove B, et al. Intracoronary injection of CD133-positive enriched bone marrow progenitor cells promotes cardiac recovery after recent myocardial infarction: feasibility and safety. Circulation. 2005; 112(9 Suppl):I178–I183. PMID: 16159812.

Article23. Li ZQ, Zhang M, Jing YZ, et al. The clinical study of autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation by intracoronary infusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Int J Cardiol. 2007; 115:52–56. PMID: 16822566.24. Boyle AJ, Whitbourn R, Schlicht S, et al. Intra-coronary high-dose CD34+ stem cells in patients with chronic ischemic heart disease: a 12-month follow-up. Int J Cardiol. 2006; 109:21–27. PMID: 15970342.

Article25. Stamm C, Kleine HD, Choi YH, et al. Intramyocardial delivery of CD133+ bone marrow cells and coronary artery bypass grafting for chronic ischemic heart disease: safety and efficacy studies. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007; 133:717–725. PMID: 17320570.

Article26. Losordo DW, Henry TD, Davidson C, et al. Intramyocardial, autologous CD34+ cell therapy for refractory angina. Circ Res. 2011; 109:428–436. PMID: 21737787.

Article27. Losordo DW, Schatz RA, White CJ, et al. Intramyocardial transplantation of autologous CD34+ stem cells for intractable angina: a phase I/IIa double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2007; 115:3165–3172. PMID: 17562958.28. Burt RK, Testori A, Oyama Y, et al. Autologous peripheral blood CD133+ cell implantation for limb salvage in patients with critical limb ischemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010; 45:111–116. PMID: 19448678.

Article29. Kuroda R, Matsumoto T, Miwa M, et al. Local transplantation of G-CSF-mobilized CD34(+) cells in a patient with tibial nonunion: a case report. Cell Transplant. 2011; 20:1491–1496. PMID: 21176407.

Article30. Assmus B, Schachinger V, Teupe C, et al. Transplantation of Progenitor Cells and Regeneration Enhancement in Acute Myocardial Infarction (TOPCARE-AMI). Circulation. 2002; 106:3009–3017. PMID: 12473544.

Article31. Hare JM, Traverse JH, Henry TD, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of intravenous adult human mesenchymal stem cells (prochymal) after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:2277–2286. PMID: 19958962.32. Assmus B, Honold J, Schächinger V, et al. Transcoronary transplantation of progenitor cells after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:1222–1232. PMID: 16990385.

Article33. Tatsumi T, Ashihara E, Yasui T, et al. Intracoronary transplantation of non-expanded peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells promotes improvement of cardiac function in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ J. 2007; 71:1199–1207. PMID: 17652881.

Article34. Schaefer A, Meyer GP, Fuchs M, et al. Impact of intracoronary bone marrow cell transfer on diastolic function in patients after acute myocardial infarction: results from the BOOST trial. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27:929–935. PMID: 16510465.

Article35. Janssens S, Dubois C, Bogaert J, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived stem-cell transfer in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006; 367:113–121. PMID: 16413875.

Article36. Lunde K, Solheim S, Aakhus S, et al. Intracoronary injection of mononuclear bone marrow cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:1199–1209. PMID: 16990383.37. Meyer GP, Wollert KC, Lotz J, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: eighteen months' follow-up data from the randomized, controlled BOOST (BOne marrOw transfer to enhance ST-elevation infarct regeneration) trial. Circulation. 2006; 113:1287–1294. PMID: 16520413.38. Penicka M, Horak J, Kobylka P, et al. Intracoronary injection of autologous bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells in patients with large anterior acute myocardial infarction: a prematurely terminated randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 49:2373–2374. PMID: 17572255.39. Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, et al. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res. 1999; 85:221–228. PMID: 10436164.

Article40. Masuda H, Kalka C, Takahashi T, et al. Estrogen-mediated endothelial progenitor cell biology and kinetics for physiological postnatal vasculogenesis. Circ Res. 2007; 101:598–606. PMID: 17656679.

Article41. Bauer SM, Goldstein LJ, Bauer RJ, Chen H, Putt M, Velazquez OC. The bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cell response is impaired in delayed wound healing from ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2006; 43:134–141. PMID: 16414400.

Article42. Ii M, Nishimura H, Iwakura A, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells are rapidly recruited to myocardium and mediate protective effect of ischemic preconditioning via "imported" nitric oxide synthase activity. Circulation. 2005; 111:1114–1120. PMID: 15723985.

Article43. Iwakura A, Shastry S, Luedemann C, et al. Estradiol enhances recovery after myocardial infarction by augmenting incorporation of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells into sites of ischemia-induced neovascularization via endothelial nitric oxide synthase-mediated activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Circulation. 2006; 113:1605–1614. PMID: 16534014.

Article44. Murayama T, Tepper OM, Silver M, et al. Determination of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cell significance in angiogenic growth factor-induced neovascularization in vivo. Exp Hematol. 2002; 30:967–972. PMID: 12160849.

Article45. Jackson KA, Majka SM, Wang H, et al. Regeneration of ischemic cardiac muscle and vascular endothelium by adult stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2001; 107:1395–1402. PMID: 11390421.

Article46. Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, et al. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001; 410:701–705. PMID: 11287958.

Article47. Yeh ET, Zhang S, Wu HD, Körbling M, Willerson JT, Estrov Z. Transdifferentiation of human peripheral blood CD34+-enriched cell population into cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells in vivo. Circulation. 2003; 108:2070–2073. PMID: 14568894.48. Balsam LB, Wagers AJ, Christensen JL, Kofidis T, Weissman IL, Robbins RC. Haematopoietic stem cells adopt mature haematopoietic fates in ischaemic myocardium. Nature. 2004; 428:668–673. PMID: 15034594.

Article49. Murry CE, Soonpaa MH, Reinecke H, et al. Haematopoietic stem cells do not transdifferentiate into cardiac myocytes in myocardial infarcts. Nature. 2004; 428:664–668. PMID: 15034593.

Article50. Ziegelhoeffer T, Fernandez B, Kostin S, et al. Bone marrow-derived cells do not incorporate into the adult growing vasculature. Circ Res. 2004; 94:230–238. PMID: 14656934.

Article51. Urbich C, Aicher A, Heeschen C, et al. Soluble factors released by endothelial progenitor cells promote migration of endothelial cells and cardiac resident progenitor cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005; 39:733–742. PMID: 16199052.

Article52. Cho HJ, Lee N, Lee JY, et al. Role of host tissues for sustained humoral effects after endothelial progenitor cell transplantation into the ischemic heart. J Exp Med. 2007; 204:3257–3269. PMID: 18070934.

Article53. Miyamoto Y, Suyama T, Yashita T, Akimaru H, Kurata H. Bone marrow subpopulations contain distinct types of endothelial progenitor cells and angiogenic cytokine-producing cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007; 43:627–635. PMID: 17900610.

Article54. Rehman J, Li J, Orschell CM, March KL. Peripheral blood "endothelial progenitor cells" are derived from monocyte/macrophages and secrete angiogenic growth factors. Circulation. 2003; 107:1164–1169. PMID: 12615796.

Article55. Gnecchi M, He H, Liang OD, et al. Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart by Akt-modified mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med. 2005; 11:367–368. PMID: 15812508.

Article56. Uemura R, Xu M, Ahmad N, Ashraf M. Bone marrow stem cells prevent left ventricular remodeling of ischemic heart through paracrine signaling. Circ Res. 2006; 98:1414–1421. PMID: 16690882.

Article57. Kinnaird T, Stabile E, Burnett MS, et al. Local delivery of marrow-derived stromal cells augments collateral perfusion through paracrine mechanisms. Circulation. 2004; 109:1543–1549. PMID: 15023891.

Article58. Yoon YS, Wecker A, Heyd L, et al. Clonally expanded novel multipotent stem cells from human bone marrow regenerate myocardium after myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest. 2005; 115:326–338. PMID: 15690083.

Article59. Mirotsou M, Zhang Z, Deb A, et al. Secreted frizzled related protein 2 (Sfrp2) is the key Akt-mesenchymal stem cell-released paracrine factor mediating myocardial survival and repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007; 104:1643–1648. PMID: 17251350.

Article60. He W, Zhang L, Ni A, et al. Exogenously administered secreted frizzled related protein 2 (Sfrp2) reduces fibrosis and improves cardiac function in a rat model of myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107:21110–21115. PMID: 21078975.

Article61. Kim H, Cho HJ, Kim SW, et al. CD31+ cells represent highly angiogenic and vasculogenic cells in bone marrow: novel role of nonendothelial CD31+ cells in neovascularization and their therapeutic effects on ischemic vascular disease. Circ Res. 2010; 107:602–614. PMID: 20634489.62. Kim SW, Kim H, Cho HJ, Lee JU, Levit R, Yoon YS. Human peripheral blood-derived CD31+ cells have robust angiogenic and vasculogenic properties and are effective for treating ischemic vascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 56:593–607. PMID: 20688215.63. Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997; 275:964–967. PMID: 9020076.

Article64. Dimmeler S, Burchfield J, Zeiher AM. Cell-based therapy of myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008; 28:208–216. PMID: 17951319.

Article65. Kawamoto A, Losordo DW. Endothelial progenitor cells for cardiovascular regeneration. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008; 18:33–37. PMID: 18206807.

Article66. Bertolini F, Mancuso P, Shaked Y, Kerbel RS. Molecular and cellular biomarkers for angiogenesis in clinical oncology. Drug Discov Today. 2007; 12:806–812. PMID: 17933680.

Article67. Bertolini F, Shaked Y, Mancuso P, Kerbel RS. The multifaceted circulating endothelial cell in cancer: towards marker and target identification. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006; 6:835–845. PMID: 17036040.

Article68. Schatteman GC, Dunnwald M, Jiao C. Biology of bone marrow-derived endothelial cell precursors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007; 292:H1–H18. PMID: 16980351.

Article69. Fernandez Pujol B, Lucibello FC, Gehling UM, et al. Endothelial-like cells derived from human CD14 positive monocytes. Differentiation. 2000; 65:287–300. PMID: 10929208.

Article70. Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Endothelial cell apoptosis in angiogenesis and vessel regression. Circ Res. 2000; 87:434–439. PMID: 10988233.

Article71. Dimmeler S, Aicher A, Vasa M, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) increase endothelial progenitor cells via the PI 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J Clin Invest. 2001; 108:391–397. PMID: 11489932.

Article72. Schmeisser A, Garlichs CD, Zhang H, et al. Monocytes coexpress endothelial and macrophagocytic lineage markers and form cord-like structures in Matrigel under angiogenic conditions. Cardiovasc Res. 2001; 49:671–680. PMID: 11166280.

Article73. Ingram DA, Caplice NM, Yoder MC. Unresolved questions, changing definitions, and novel paradigms for defining endothelial progenitor cells. Blood. 2005; 106:1525–1531. PMID: 15905185.

Article74. Gulati R, Jevremovic D, Peterson TE, et al. Diverse origin and function of cells with endothelial phenotype obtained from adult human blood. Circ Res. 2003; 93:1023–1025. PMID: 14605020.

Article75. Wang X, Willenbring H, Akkari Y, et al. Cell fusion is the principal source of bone-marrow-derived hepatocytes. Nature. 2003; 422:897–901. PMID: 12665832.

Article76. Kucia M, Dawn B, Hunt G, et al. Cells expressing early cardiac markers reside in the bone marrow and are mobilized into the peripheral blood after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2004; 95:1191–1199. PMID: 15550692.

Article77. Ratajczak MZ, Kucia M, Reca R, Majka M, Janowska-Wieczorek A, Ratajczak J. Stem cell plasticity revisited: CXCR4-positive cells expressing mRNA for early muscle, liver and neural cells 'hide out' in the bone marrow. Leukemia. 2004; 18:29–40. PMID: 14586476.

Article78. Zhang S, Wang D, Estrov Z, Raj S, Willerson JT, Yeh ET. Both cell fusion and transdifferentiation account for the transformation of human peripheral blood CD34-positive cells into cardiomyocytes in vivo. Circulation. 2004; 110:3803–3807. PMID: 15596566.

Article79. Folkman J. Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nat Med. 1995; 1:27–31. PMID: 7584949.

Article80. Kawamoto A, Tkebuchava T, Yamaguchi J, et al. Intramyocardial transplantation of autologous endothelial progenitor cells for therapeutic neovascularization of myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2003; 107:461–468. PMID: 12551872.

Article81. Murohara T. Therapeutic vasculogenesis using human cord blood-derived endothelial progenitors. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2001; 11:303–307. PMID: 11728877.

Article82. Stamm C, Westphal B, Kleine HD, et al. Autologous bone-marrow stem-cell transplantation for myocardial regeneration. Lancet. 2003; 361:45–46. PMID: 12517467.

Article83. Döbert N, Britten M, Assmus B, et al. Transplantation of progenitor cells after reperfused acute myocardial infarction: evaluation of perfusion and myocardial viability with FDG-PET and thallium SPECT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004; 31:1146–1151. PMID: 15064873.

Article84. Ingram DA, Mead LE, Tanaka H, et al. Identification of a novel hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells using human peripheral and umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2004; 104:2752–2760. PMID: 15226175.

Article85. Yoon CH, Hur J, Park KW, et al. Synergistic neovascularization by mixed transplantation of early endothelial progenitor cells and late outgrowth endothelial cells: the role of angiogenic cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases. Circulation. 2005; 112:1618–1627. PMID: 16145003.86. Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001; 414:105–111. PMID: 11689955.

Article87. Spangrude GJ, Heimfeld S, Weissman IL. Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 1988; 241:58–62. PMID: 2898810.

Article88. Baum CM, Weissman IL, Tsukamoto AS, Buckle AM, Peault B. Isolation of a candidate human hematopoietic stem-cell population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992; 89:2804–2808. PMID: 1372992.

Article89. Seita J, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem cell: self-renewal versus differentiation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2010; 2:640–653. PMID: 20890962.

Article90. Wang J, Zhang S, Rabinovich B, et al. Human CD34+ cells in experimental myocardial infarction: long-term survival, sustained functional improvement, and mechanism of action. Circ Res. 2010; 106:1904–1911. PMID: 20448213.91. Flores-Ramirez R, Uribe-Longoria A, Rangel-Fuentes MM, et al. Intracoronary infusion of CD133+ endothelial progenitor cells improves heart function and quality of life in patients with chronic post-infarct heart insufficiency. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2010; 11:72–78. PMID: 20347795.92. Schots R, De Keulenaer G, Schoors D, et al. Evidence that intracoronary-injected CD133+ peripheral blood progenitor cells home to the myocardium in chronic postinfarction heart failure. Exp Hematol. 2007; 35:1884–1890. PMID: 17923244.

Article93. Leor J, Guetta E, Feinberg MS, et al. Human umbilical cord blood-derived CD133+ cells enhance function and repair of the infarcted myocardium. Stem Cells. 2006; 24:772–780. PMID: 16195418.

Article94. Kamihata H, Matsubara H, Nishiue T, et al. Implantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells into ischemic myocardium enhances collateral perfusion and regional function via side supply of angioblasts, angiogenic ligands, and cytokines. Circulation. 2001; 104:1046–1052. PMID: 11524400.

Article95. Fuchs S, Baffour R, Zhou YF, et al. Transendocardial delivery of autologous bone marrow enhances collateral perfusion and regional function in pigs with chronic experimental myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 37:1726–1732. PMID: 11345391.

Article96. Strauer BE, Brehm M, Zeus T, et al. Repair of infarcted myocardium by autologous intracoronary mononuclear bone marrow cell transplantation in humans. Circulation. 2002; 106:1913–1918. PMID: 12370212.

Article97. Tateishi-Yuyama E, Matsubara H, Murohara T, et al. Therapeutic angiogenesis for patients with limb ischaemia by autologous transplantation of bone-marrow cells: a pilot study and a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002; 360:427–435. PMID: 12241713.

Article98. Perin EC, Dohmann HF, Borojevic R, et al. Transendocardial, autologous bone marrow cell transplantation for severe, chronic ischemic heart failure. Circulation. 2003; 107:2294–2302. PMID: 12707230.

Article99. Mocini D, Staibano M, Mele L, et al. Autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Am Heart J. 2006; 151:192–197. PMID: 16368317.

Article100. Leibovich SJ, Polverini PJ, Shepard HM, Wiseman DM, Shively V, Nuseir N. Macrophage-induced angiogenesis is mediated by tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Nature. 1987; 329:630–632. PMID: 2443857.101. Giulian D, Woodward J, Young DG, Krebs JF, Lachman LB. Interleukin-1 injected into mammalian brain stimulates astrogliosis and neovascularization. J Neurosci. 1988; 8:2485–2490. PMID: 2470873.

Article102. Toda H, Tsuji M, Nakano I, et al. Stem cell-derived neural stem/progenitor cell supporting factor is an autocrine/paracrine survival factor for adult neural stem/progenitor cells. J Biol Chem. 2003; 278:35491–35500. PMID: 12832409.

Article103. O'Garra A, Murphy K. Role of cytokines in development of Th1 and Th2 cells. Chem Immunol. 1996; 63:1–13. PMID: 8934828.104. Mosmann TR. Properties and functions of interleukin-10. Adv Immunol. 1994; 56:1–26. PMID: 8073945.105. Chandrasekar B, Mitchell DH, Colston JT, Freeman GL. Regulation of CCAAT/Enhancer binding protein, interleukin-6, interleukin-6 receptor, and gp130 expression during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation. 1999; 99:427–433. PMID: 9918531.

Article106. Fuchs U, Zittermann A, Suhr O, et al. Heart transplantation in a 68-year-old patient with senile systemic amyloidosis. Am J Transplant. 2005; 5:1159–1162. PMID: 15816901.

Article107. Barcelos LS, Duplaa C, Krankel N, et al. Human CD133+ progenitor cells promote the healing of diabetic ischemic ulcers by paracrine stimulation of angiogenesis and activation of Wnt signaling. Circ Res. 2009; 104:1095–1102. PMID: 19342601.108. Tolar J, Nauta AJ, Osborn MJ, et al. Sarcoma derived from cultured mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007; 25:371–379. PMID: 17038675.

Article109. Tateno K, Minamino T, Toko H, et al. Critical roles of muscle-secreted angiogenic factors in therapeutic neovascularization. Circ Res. 2006; 98:1194–1202. PMID: 16574905.

Article110. Terada N, Hamazaki T, Oka M, et al. Bone marrow cells adopt the phenotype of other cells by spontaneous cell fusion. Nature. 2002; 416:542–545. PMID: 11932747.

Article111. Ying QL, Nichols J, Evans EP, Smith AG. Changing potency by spontaneous fusion. Nature. 2002; 416:545–548. PMID: 11932748.

Article112. Nygren JM, Jovinge S, Breitbach M, et al. Bone marrow-derived hematopoietic cells generate cardiomyocytes at a low frequency through cell fusion, but not transdifferentiation. Nat Med. 2004; 10:494–501. PMID: 15107841.

Article113. Alvarez-Dolado M, Pardal R, Garcia-Verdugo JM, et al. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature. 2003; 425:968–973. PMID: 14555960.

Article114. Albelda SM, Muller WA, Buck CA, Newman PJ. Molecular and cellular properties of PECAM-1 (endoCAM/CD31): a novel vascular cell-cell adhesion molecule. J Cell Biol. 1991; 114:1059–1068. PMID: 1874786.

Article115. Xie Y, Muller WA. Molecular cloning and adhesive properties of murine platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993; 90:5569–5573. PMID: 8516303.

Article116. Muller WA, Weigl SA, Deng X, Phillips DM. PECAM-1 is required for transendothelial migration of leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1993; 178:449–460. PMID: 8340753.

Article117. Berman ME, Xie Y, Muller WA. Roles of platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1, CD31) in natural killer cell transendothelial migration and beta 2 integrin activation. J Immunol. 1996; 156:1515–1524. PMID: 8568255.118. Voermans C, Rood PM, Hordijk PL, Gerritsen WR, van der Schoot CE. Adhesion molecules involved in transendothelial migration of human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2000; 18:435–443. PMID: 11072032.

Article119. Zocchi MR, Ferrero E, Leone BE, et al. CD31/PECAM-1-driven chemokine-independent transmigration of human T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1996; 26:759–767. PMID: 8625965.

Article120. Schenkel AR, Chew TW, Muller WA. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule deficiency or blockade significantly reduces leukocyte emigration in a majority of mouse strains. J Immunol. 2004; 173:6403–6408. PMID: 15528380.

Article121. Noble KE, Wickremasinghe RG, DeCornet C, Panayiotidis P, Yong KL. Monocytes stimulate expression of the Bcl-2 family member, A1, in endothelial cells and confer protection against apoptosis. J Immunol. 1999; 162:1376–1383. PMID: 9973392.122. Ilan N, Mohsenin A, Cheung L, Madri JA. PECAM-1 shedding during apoptosis generates a membrane-anchored truncated molecule with unique signaling characteristics. FASEB J. 2001; 15:362–372. PMID: 11156952.

Article123. Newman PJ, Berndt MC, Gorski J, et al. PECAM-1 (CD31) cloning and relation to adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily. Science. 1990; 247:1219–1222. PMID: 1690453.

Article124. DeLisser HM, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Strieter RM, et al. Involvement of endothelial PECAM-1/CD31 in angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1997; 151:671–677. PMID: 9284815.125. Matsumura T, Wolff K, Petzelbauer P. Endothelial cell tube formation depends on cadherin 5 and CD31 interactions with filamentous actin. J Immunol. 1997; 158:3408–3416. PMID: 9120301.126. Cao G, O'Brien CD, Zhou Z, et al. Involvement of human PECAM-1 in angiogenesis and in vitro endothelial cell migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002; 282:C1181–C1190. PMID: 11940533.

Article127. Iivanainen E, Nelimarkka L, Elenius V, et al. Angiopoietin-regulated recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells by endothelial-derived heparin binding EGF-like growth factor. FASEB J. 2003; 17:1609–1621. PMID: 12958167.

Article128. Koch AE, Polverini PJ, Kunkel SL, et al. Interleukin-8 as a macrophage-derived mediator of angiogenesis. Science. 1992; 258:1798–1801. PMID: 1281554.

Article129. Cho CH, Kammerer RA, Lee HJ, et al. COMP-Ang1: a designed angiopoietin-1 variant with nonleaky angiogenic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004; 101:5547–5552. PMID: 15060279.

Article130. Jones N, Iljin K, Dumont DJ, Alitalo K. Tie receptors: new modulators of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic responses. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001; 2:257–267. PMID: 11283723.

Article131. Mammoto A, Connor KM, Mammoto T, et al. A mechanosensitive transcriptional mechanism that controls angiogenesis. Nature. 2009; 457:1103–1108. PMID: 19242469.

Article132. Lee P, Goishi K, Davidson AJ, Mannix R, Zon L, Klagsbrun M. Neuropilin-1 is required for vascular development and is a mediator of VEGF-dependent angiogenesis in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002; 99:10470–10475. PMID: 12142468.

Article133. Shi Q, Rafii S, Wu MH, et al. Evidence for circulating bone marrow-derived endothelial cells. Blood. 1998; 92:362–367. PMID: 9657732.

Article134. Lyden D, Hattori K, Dias S, et al. Impaired recruitment of bone-marrow-derived endothelial and hematopoietic precursor cells blocks tumor angiogenesis and growth. Nat Med. 2001; 7:1194–1201. PMID: 11689883.

Article135. O'Neill TJ 4th, Wamhoff BR, Owens GK, Skalak TC. Mobilization of bone marrow-derived cells enhances the angiogenic response to hypoxia without transdifferentiation into endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2005; 97:1027–1035. PMID: 16210550.136. Smits AM, van Laake LW, den Ouden K, et al. Human cardiomyocyte progenitor cell transplantation preserves long-term function of the infarcted mouse myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 2009; 83:527–535. PMID: 19429921.

Article137. Tang XL, Rokosh DG, Guo Y, Bolli R. Cardiac progenitor cells and bone marrow-derived very small embryonic-like stem cells for cardiac repair after myocardial infarction. Circ J. 2010; 74:390–404. PMID: 20081317.

Article138. Smith RR, Barile L, Cho HC, et al. Regenerative potential of cardiosphere-derived cells expanded from percutaneous endomyocardial biopsy specimens. Circulation. 2007; 115:896–908. PMID: 17283259.

Article139. Virag JI, Murry CE. Myofibroblast and endothelial cell proliferation during murine myocardial infarct repair. Am J Pathol. 2003; 163:2433–2440. PMID: 14633615.

Article140. Gao D, Nolan DJ, Mellick AS, Bambino K, McDonnell K, Mittal V. Endothelial progenitor cells control the angiogenic switch in mouse lung metastasis. Science. 2008; 319:195–198. PMID: 18187653.

Article141. Nolan DJ, Ciarrocchi A, Mellick AS, et al. Bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells are a major determinant of nascent tumor neovascularization. Genes Dev. 2007; 21:1546–1558. PMID: 17575055.

Article142. Müller-Ehmsen J, Whittaker P, Kloner RA, et al. Survival and development of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes transplanted into adult myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002; 34:107–116. PMID: 11851351.

Article143. Musialek P, Tekieli L, Kostkiewicz M, et al. Randomized transcoronary delivery of CD34(+) cells with perfusion versus stop-flow method in patients with recent myocardial infarction: Early cardiac retention of 99(m)Tc-labeled cells activity. J Nucl Cardiol. 2011; 18:104–116. PMID: 21161463.144. Zocchi MR, Poggi A. Lymphocyte-endothelial cell adhesion molecules at the primary tumor site in human lung and renal cell carcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993; 85:246–247. PMID: 7678655.

Article145. Woodfin A, Voisin MB, Nourshargh S. PECAM-1: a multi-functional molecule in inflammation and vascular biology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007; 27:2514–2523. PMID: 17872453.

Article146. Kawamoto A, Katayama M, Handa N, et al. Intramuscular transplantation of G-CSF-mobilized CD34(+) cells in patients with critical limb ischemia: a phase I/IIa, multicenter, single-blinded, dose-escalation clinical trial. Stem Cells. 2009; 27:2857–2864. PMID: 19711453.

Article147. Kang HJ, Kim HS, Zhang SY, et al. Effects of intracoronary infusion of peripheral blood stem-cells mobilised with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor on left ventricular systolic function and restenosis after coronary stenting in myocardial infarction: the MAGIC cell randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2004; 363:751–756. PMID: 15016484.

Article148. Horwitz EM, Gordon PL, Koo WK, et al. Isolated allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells engraft and stimulate growth in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: Implications for cell therapy of bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002; 99:8932–8937. PMID: 12084934.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Generation and Characterization of Alloenic Radiation Bone Marrow Chimera

- Bone marrow-derived stem cells contribute to regeneration of the endometrium

- An Immune-compromised Method for Tooth Transplantation Using Adult Bone Marrow Stromal Cells and Embryonic Tooth Germ

- Neural Differentiation of Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Applicability for Inner Ear Therapy

- Stem Cell Research in Cardiovascular System