Brain Tumor Res Treat.

2013 Apr;1(1):9-15. 10.14791/btrt.2013.1.1.9.

Molecular Culprits Generating Brain Tumor Stem Cells

- Affiliations

-

- 1School of Life Science and Biotechnology, Korea University, Seoul, Korea. hg-kim@korea.ac.kr

- KMID: 2165216

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14791/btrt.2013.1.1.9

Abstract

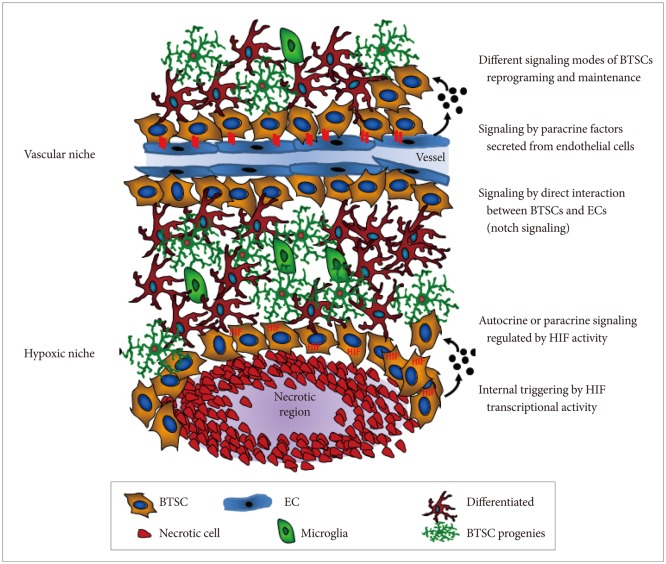

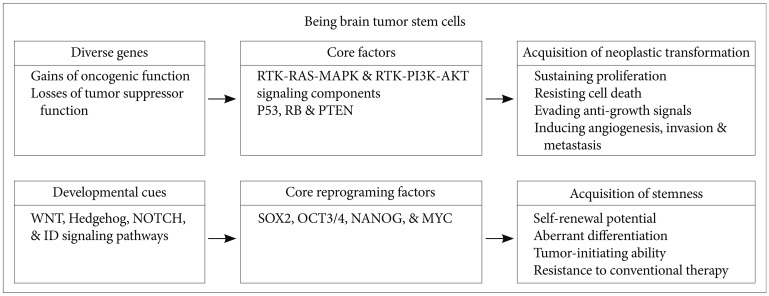

- Despite current advances in multimodality therapies, such as surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, the outcome for patients with high-grade glioma remains fatal. Understanding how glioma cells resist various therapies may provide opportunities for developing new therapies. Accumulating evidence suggests that the main obstacle for successfully treating high-grade glioma is the existence of brain tumor stem cells (BTSCs), which share a number of cellular properties with adult stem cells, such as self-renewal and multipotent differentiation capabilities. Owing to their resistance to standard therapy coupled with their infiltrative nature, BTSCs are a primary cause of tumor recurrence post-therapy. Therefore, BTSCs are thought to be the main glioma cells representing a novel therapeutic target and should be eliminated to obtain successful treatment outcomes.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Blondin NA, Becker KP. Anaplastic gliomas: radiation, chemotherapy, or both? Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2012; 26:811–823. PMID: 22794285.2. Rahman M, Hoh B, Kohler N, Dunbar EM, Murad GJ. The future of glioma treatment: stem cells, nanotechnology and personalized medicine. Future Oncol. 2012; 8:1149–1156. PMID: 23030489.

Article3. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:987–996. PMID: 15758009.

Article4. Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:492–507. PMID: 18669428.

Article5. Clarke MF, Fuller M. Stem cells and cancer: two faces of eve. Cell. 2006; 124:1111–1115. PMID: 16564000.

Article6. Sanai N, Alvarez-Buylla A, Berger MS. Neural stem cells and the origin of gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:811–822. PMID: 16120861.

Article7. Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006; 444:756–760. PMID: 17051156.

Article8. Chen J, Li Y, Yu TS, et al. A restricted cell population propagates glioblastoma growth after chemotherapy. Nature. 2012; 488:522–526. PMID: 22854781.

Article9. Moore KA, Lemischka IR. Stem cells and their niches. Science. 2006; 311:1880–1885. PMID: 16574858.

Article10. Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M, et al. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007; 11:69–82. PMID: 17222791.

Article11. Fuchs E, Tumbar T, Guasch G. Socializing with the neighbors: stem cells and their niche. Cell. 2004; 116:769–778. PMID: 15035980.12. Tavazoie M, Van der Veken L, Silva-Vargas V, et al. A specialized vascular niche for adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008; 3:279–288. PMID: 18786415.

Article13. Zhu TS, Costello MA, Talsma CE, et al. Endothelial cells create a stem cell niche in glioblastoma by providing NOTCH ligands that nurture self-renewal of cancer stem-like cells. Cancer Res. 2011; 71:6061–6072. PMID: 21788346.

Article14. Altaner C. Glioblastoma and stem cells. Neoplasma. 2008; 55:369–374. PMID: 18665745.15. Lim DA, Cha S, Mayo MC, et al. Relationship of glioblastoma multiforme to neural stem cell regions predicts invasive and multifocal tumor phenotype. Neuro Oncol. 2007; 9:424–429. PMID: 17622647.

Article16. Wodarz A, Gonzalez C. Connecting cancer to the asymmetric division of stem cells. Cell. 2006; 124:1121–1123. PMID: 16564003.

Article17. Gilbertson RJ, Rich JN. Making a tumour's bed: glioblastoma stem cells and the vascular niche. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007; 7:733–736. PMID: 17882276.

Article18. Fujii S, Sawa T, Ihara H, et al. The critical role of nitric oxide signaling, via protein S-guanylation and nitrated cyclic GMP, in the antioxidant adaptive response. J Biol Chem. 2010; 285:23970–23984. PMID: 20498371.

Article19. Lim KH, Ancrile BB, Kashatus DF, Counter CM. Tumour maintenance is mediated by eNOS. Nature. 2008; 452:646–649. PMID: 18344980.

Article20. Charles N, Ozawa T, Squatrito M, et al. Perivascular nitric oxide activates notch signaling and promotes stem-like character in PDGF-induced glioma cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010; 6:141–152. PMID: 20144787.

Article21. Broholm H, Rubin I, Kruse A, et al. Nitric oxide synthase expression and enzymatic activity in human brain tumors. Clin Neuropathol. 2003; 22:273–281. PMID: 14672505.22. Blaise GA, Gauvin D, Gangal M, Authier S. Nitric oxide, cell signaling and cell death. Toxicology. 2005; 208:177–192. PMID: 15691583.

Article23. Fukumura D, Kashiwagi S, Jain RK. The role of nitric oxide in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006; 6:521–534. PMID: 16794635.

Article24. Borovski T, De Sousa E Melo F, Vermeulen L, Medema JP. Cancer stem cell niche: the place to be. Cancer Res. 2011; 71:634–639. PMID: 21266356.25. Perk J, Iavarone A, Benezra R. Id family of helix-loop-helix proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005; 5:603–614. PMID: 16034366.

Article26. Alani RM, Young AZ, Shifflett CB. Id1 regulation of cellular senescence through transcriptional repression of p16/Ink4a. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001; 98:7812–7816. PMID: 11427735.

Article27. O'Brien CA, Kreso A, Ryan P, et al. ID1 and ID3 regulate the self-renewal capacity of human colon cancer-initiating cells through p21. Cancer Cell. 2012; 21:777–792. PMID: 22698403.28. Benezra R, Rafii S, Lyden D. The Id proteins and angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2001; 20:8334–8341. PMID: 11840326.

Article29. Gupta GP, Perk J, Acharyya S, et al. ID genes mediate tumor reinitiation during breast cancer lung metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007; 104:19506–19511. PMID: 18048329.

Article30. Lyden D, Young AZ, Zagzag D, et al. Id1 and Id3 are required for neurogenesis, angiogenesis and vascularization of tumour xenografts. Nature. 1999; 401:670–677. PMID: 10537105.

Article31. Jung S, Park RH, Kim S, et al. Id proteins facilitate self-renewal and proliferation of neural stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2010; 19:831–841. PMID: 19757990.

Article32. Venneti S, Le P, Martinez D, et al. Malignant rhabdoid tumors express stem cell factors, which relate to the expression of EZH2 and Id proteins. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011; 35:1463–1472. PMID: 21921784.

Article33. Jeon HM, Jin X, Lee JS, et al. Inhibitor of differentiation 4 drives brain tumor-initiating cell genesis through cyclin E and notch signaling. Genes Dev. 2008; 22:2028–2033. PMID: 18676808.

Article34. Jin X, Yin J, Kim SH, et al. EGFR-AKT-Smad signaling promotes formation of glioma stem-like cells and tumor angiogenesis by ID3-driven cytokine induction. Cancer Res. 2011; 71:7125–7134. PMID: 21975932.

Article35. Anido J, Sáez-Borderías A, Gonzàlez-Juncà A, et al. TGF-β Receptor Inhibitors Target the CD44(high)/Id1(high) Glioma-Initiating Cell Population in Human Glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2010; 18:655–668. PMID: 21156287.

Article36. Dunwoodie SL. The role of hypoxia in development of the Mammalian embryo. Dev Cell. 2009; 17:755–773. PMID: 20059947.

Article37. Mazumdar J, Dondeti V, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors in stem cells and cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2009; 13:4319–4328. PMID: 19900215.

Article38. Diabira S, Morandi X. Gliomagenesis and neural stem cells: key role of hypoxia and concept of tumor "neo-niche". Med Hypotheses. 2008; 70:96–104. PMID: 17614215.

Article39. Morrison SJ, Csete M, Groves AK, Melega W, Wold B, Anderson DJ. Culture in reduced levels of oxygen promotes clonogenic sympathoadrenal differentiation by isolated neural crest stem cells. J Neurosci. 2000; 20:7370–7376. PMID: 11007895.

Article40. Konietzny R, König A, Wotzlaw C, Bernadini A, Berchner-Pfannschmidt U, Fandrey J. Molecular imaging: into in vivo interaction of HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha with ARNT. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009; 1177:74–81. PMID: 19845609.41. Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995; 92:5510–5514. PMID: 7539918.

Article42. Jubb AM, Buffa FM, Harris AL. Assessment of tumour hypoxia for prediction of response to therapy and cancer prognosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2010; 14:18–29. PMID: 19840191.

Article43. Liu L, Zhu XD, Wang WQ, et al. Activation of beta-catenin by hypoxia in hepatocellular carcinoma contributes to enhanced metastatic potential and poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2010; 16:2740–2750. PMID: 20460486.44. DeClerck K, Elble RC. The role of hypoxia and acidosis in promoting metastasis and resistance to chemotherapy. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2010; 15:213–225. PMID: 20036816.

Article45. Wartenberg M, Ling FC, Müschen M, et al. Regulation of the multidrug resistance transporter P-glycoprotein in multicellular tumor spheroids by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) and reactive oxygen species. FASEB J. 2003; 17:503–505. PMID: 12514119.46. Graeber TG, Osmanian C, Jacks T, et al. Hypoxia-mediated selection of cells with diminished apoptotic potential in solid tumours. Nature. 1996; 379:88–91. PMID: 8538748.

Article47. Chan N, Koch CJ, Bristow RG. Tumor hypoxia as a modifier of DNA strand break and cross-link repair. Curr Mol Med. 2009; 9:401–410. PMID: 19519397.

Article48. Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006; 126:663–676. PMID: 16904174.

Article49. Schoenhals M, Kassambara A, De Vos J, Hose D, Moreaux J, Klein B. Embryonic stem cell markers expression in cancers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009; 383:157–162. PMID: 19268426.

Article50. Suvà ML, Riggi N, Bernstein BE. Epigenetic reprogramming in cancer. Science. 2013; 339:1567–1570. PMID: 23539597.

Article51. O'Brien CA, Kreso A, Jamieson CH. Cancer stem cells and self-renewal. Clin Cancer Res. 2010; 16:3113–3120. PMID: 20530701.52. Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003; 100:3983–3988. PMID: 12629218.

Article53. Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997; 3:730–737. PMID: 9212098.

Article54. Collins AT, Berry PA, Hyde C, Stower MJ, Maitland NJ. Prospective identification of tumorigenic prostate cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2005; 65:10946–10951. PMID: 16322242.

Article55. Galli R, Binda E, Orfanelli U, et al. Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem-like neural precursors from human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2004; 64:7011–7021. PMID: 15466194.

Article56. Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007; 445:111–115. PMID: 17122771.

Article57. Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003; 63:5821–5828. PMID: 14522905.58. Kim KJ, Lee KH, Kim HS, et al. The presence of stem cell marker-expressing cells is not prognostically significant in glioblastomas. Neuropathology. 2011; 31:494–502. PMID: 21269333.

Article59. Thon N, Damianoff K, Hegermann J, et al. Presence of pluripotent CD133+ cells correlates with malignancy of gliomas. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010; 43:51–59. PMID: 18761091.

Article60. Beck S, Jin X, Yin J, et al. Identification of a peptide that interacts with Nestin protein expressed in brain cancer stem cells. Biomaterials. 2011; 32:8518–8528. PMID: 21880363.

Article61. Jin X, Jin X, Jung JE, Beck S, Kim H. Cell surface Nestin is a biomarker for glioma stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013; 433:496–501. PMID: 23524267.

Article62. Toda M, Iizuka Y, Yu W, et al. Expression of the neural RNA-binding protein Musashi1 in human gliomas. Glia. 2001; 34:1–7. PMID: 11284014.

Article63. Du Z, Jia D, Liu S, et al. Oct4 is expressed in human gliomas and promotes colony formation in glioma cells. Glia. 2009; 57:724–733. PMID: 18985733.

Article64. Jeon HM, Sohn YW, Oh SY, et al. ID4 imparts chemoresistance and cancer stemness to glioma cells by derepressing miR-9*-mediated suppression of SOX2. Cancer Res. 2011; 71:3410–3421. PMID: 21531766.

Article65. Jin X, Kim SH, Jeon HM, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 7 regulates glioma stem cells via interleukin-6 and Notch signalling. Brain. 2012; 135:1055–1069. PMID: 22434214.

Article66. Monk M, Holding C. Human embryonic genes re-expressed in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2001; 20:8085–8091. PMID: 11781821.

Article67. Atlasi Y, Mowla SJ, Ziaee SA, Bahrami AR. OCT-4, an embryonic stem cell marker, is highly expressed in bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007; 120:1598–1602. PMID: 17205510.

Article68. Tai MH, Chang CC, Kiupel M, Webster JD, Olson LK, Trosko JE. Oct4 expression in adult human stem cells: evidence in support of the stem cell theory of carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2005; 26:495–502. PMID: 15513931.

Article69. Dahlrot RH, Hermansen SK, Hansen S, Kristensen BW. What is the clinical value of cancer stem cell markers in gliomas? Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013; 6:334–348. PMID: 23412423.70. Hochedlinger K, Yamada Y, Beard C, Jaenisch R. Ectopic expression of Oct-4 blocks progenitor-cell differentiation and causes dysplasia in epithelial tissues. Cell. 2005; 121:465–477. PMID: 15882627.

Article71. Annovazzi L, Mellai M, Caldera V, Valente G, Schiffer D. SOX2 expression and amplification in gliomas and glioma cell lines. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2011; 8:139–147. PMID: 21518820.72. Liu K, Lin B, Zhao M, et al. The multiple roles for Sox2 in stem cell maintenance and tumorigenesis. Cell Signal. 2013; 25:1264–1271. PMID: 23416461.

Article73. Luo W, Li S, Peng B, Ye Y, Deng X, Yao K. Embryonic stem cells markers SOX2, OCT4 and Nanog expression and their correlations with epithelial-mesenchymal transition in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e56324. PMID: 23424657.

Article74. Wegner M, Stolt CC. From stem cells to neurons and glia: a Soxist's view of neural development. Trends Neurosci. 2005; 28:583–588. PMID: 16139372.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Advances in Understanding the Molecular Biology of Brain Tumors

- Cancer Stem Cells in Brain Tumors and Their Lineage Hierarchy

- Brain Tumor Stem Cells as Therapeutic Targets in Models of Glioma

- Neural Stem Cells and Ischemic Brain

- Gliomatosis Cerebri in the Brain Stem and Unilateral Cerebellar Hemisphere: Case Report