J Korean Med Assoc.

2009 Sep;52(9):871-879. 10.5124/jkma.2009.52.9.871.

Physician's Role and Obligation in the Withdrawal of Life-sustaining Management

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Ulsan University College of Medicine, Korea. yskoh@amc.seoul.kr

- KMID: 1936491

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2009.52.9.871

Abstract

- Patients should be treated with dignity and respect toward the end of their lives, being freed from unnecessary and painful life-sustaining therapy in hospitals. In Korea, the quality of endof-life (EOL) care has been variable, a major factor being the physicians' perception to the care. A firm consensus of EOL care decision-making has not yet explicitly stated in Korean law and ethics until recently. However, movements to make a law of so-called "the death with dignity act" are presently making its way to the National Assembly, initiated by a law case that allowed the hospital to withdraw mechanical ventilator support per request by the patients' family of a permanently vegetative patient. Socially agreed guidelines for EOL care can facilitate clinical decision process and communication between health service provider and the patient or his/her family. At the same time, EOL care should be individualized also in the same line of guideline to meet patient' and patient' family wish regarding the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy. The painful EOL care experience of the loved one remains in the memory of the relatives who live on. Physicians should identify, document, respect, and act on behalf of the hospitalized patients' needs, priorities, and preference for EOL care. It has been advocated that competent patients can express their right of self-determination on EOL care through advance directives in Western countries. Advance directives are considered as a tool to facilitate EOL decision making. However, there are barriers to adopt the advance directives as a legitimate tool for an EOL decision making in Korea. For one thing, the reality of death and dying is rarely discussed in our society. In addition, the discussion about EOL care with chronically and critically ill patients has been considered as a taboo in the hospitals. In spite of these difficulties, physicians could do better EOL care by the open communication with patients or with their surrogates. Through the communication, physician should set a goal how to manage the EOL patient. The set goal should be shared among the caregivers to achieve the maximum benefit of the patient. The lack of open discussion with patient prior to EOL care results in inappropriate protraction of a patient's dying process. In summary, physicians, who know the clinical significance of delivering treatments to EOL patients, should play a central role in assisting patients' and their families' to make the best decision on EOL care. Moreover, the concerted actions to improve EOL care in our society among general public, professionals, stakeholders for EOL care, and governmental organizations are required to address ongoing social requests, although a policy or a guideline is made in this time.

MeSH Terms

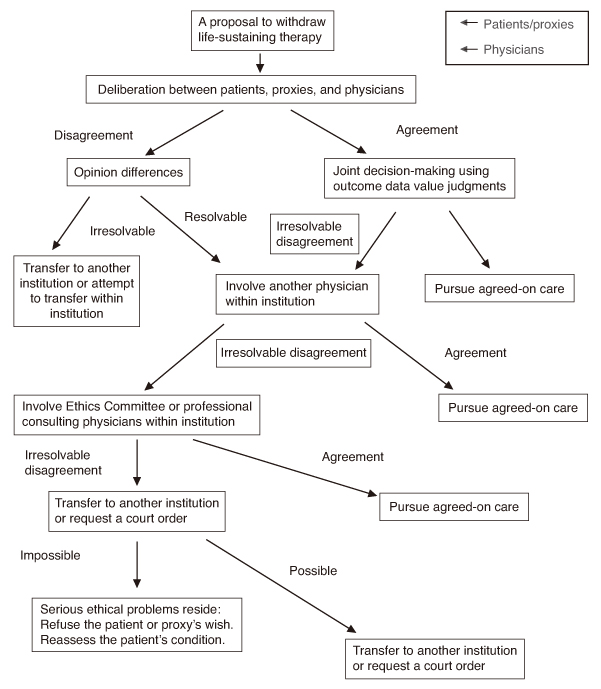

Figure

Reference

-

1. Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, Weissfeld LA, Watson RS, Rickert T, Rubenfeld GD. Robert Wood Johnson foundation ICU end-of-life peer group. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004. 32:638–643.

Article2. Prendergast TJ, Claessens MT, Luce JM, Prendergast TJ, Claessens MT, Luce JM. A national survey of end-of-life care for critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998. 158:1163–1167.

Article3. Sinuff T, Giacomini M, Shaw R, Swinton M, Cook DJ. "Living with dying": the evolution of family members' experience of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2009. 37:154–158.

Article4. Pochard F, Darmon M, Fassier T, Bollaert PE, Cheval C, Coloigner M, Merouani A, Moulront S, Pigne E, Pingat J, Zahar JR, Schlemmer B, Azoulay E. French FAMIREA study group. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients before discharge or death. A prospective multicenter study. J Crit Care. 2005. 20:90–96.

Article5. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, Annane D, Bleichner G, Bollaert PE, Darmon M, Fassier T, Galliot R, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Goulenok C, Goldgran-Toledano D, Hayon J, Jourdain M, Kaidomar M, Laplace C, LarchÈ J, Liotier J, Papazian L, Poisson C, Reignier J, Saidi F, Schlemmer B. FAMIREA Study Group. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005. 171:987–994.

Article6. Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, Haas CE, Luce JM, Rubenfeld GD, Rushton CH, Kaufman DC. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College [corrected] of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008. 36:953–963.

Article7. The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA. 1995. 274:1591–1598.8. Fassier T, Lautrette A, Ciroldi M, Azoulay E. Care at the end of life in critically ill patients: the European perspective. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005. 11:616–623.

Article9. Consensus report on the ethics of foregoing life-sustaining treatments in the critically ill. Task Force on Ethics of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1990. 18:1435–1439.10. Medical futility in end-of-life care: report of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. JAMA. 1999. 281:937–941.11. Azoulay E, Metnitz B, Sprung CL, Timsit JF, Lemaire F, Bauer P, Schlemmer B, Moreno R, Metnitz P. SAPS 3 investigators. End-of-life practices in 282 intensive care units: data from the SAPS 3 database. Intensive Care Med. 2009. 35:623–630.

Article12. Song TJ, Kim KP, Koh Y. Factors determining the establishment of DNR orders in oncologic patients at a university hospital in Korea. Korean J Med. 2008. 74:403–410.13. Lee KH, Jang HJ, Hong SB, Lim CM, Koh Y. Do-not-resuscitate order in patients, who were decreased in a Medical Intensive Care Unit of an University Hospital in Korea. Korean J Crit Care Med. 2008. 23:84–89.

Article14. Camhi SL, Mercado AF, Morrison RS, Du Q, Platt DM, August GI, Nelson JE. Deciding in the dark: advance directives and continuation of treatment in chronic critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2009. 37:919–925.

Article15. Lautrette A, Peigne V, Watts J, Souweine B, Azoulay E. Surrogate decision makers for incompetent ICU patients: a European perspective. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008. 14:714–719.

Article16. Doig C, Murray H, Bellomo R, Kuiper M, Costa R, Azoulay E, Crippen D. Ethics roundtable debate: patients and surrogates want 'everything done'-what does 'everything' mean? Crit Care. 2006. 10:231.17. Tibballs J. Legal basis for ethical withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining medical treatment from infants and children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007. 43:230–236.

Article18. Anonymous . Medical futility in end-of-life care: report of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. [see comment]. JAMA. 1999. 281:937–941.19. Schneiderman LJ, Jecker NS, Jonsen AR. Medical futility: its meaning and ethical implications. [see comment]. Ann Intern Med. 1990. 112:949–954.

Article20. Kierner KA, Hladschik-Kermer B, Gartner V, Watzke HH. Attitudes of patients with malignancies towards completion of advance directives. Support Care Cancer. 2009.

Article21. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Adrie C, Annane D, Bleichner G, Bornstain C, Bouffard Y, Cohen Y, Feissel M, Goldgran-Toledano D, Guitton C, Hayon J, Iglesias E, Joly LM, Jourdain M, Laplace C, Lebert C, Pingat J, Poisson C, Renault A, Sanchez O, Selcer D, Timsit JF, Le Gall JR, Schlemmer B. FAMIREA Study Group. Half the family members of intensive care unit patients do not want to share in the decision-making process: a study in 78 French intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2004. 32:1832–1838.

Article22. Reynolds S, Cooper AB, McKneally M. Withdrawing life-sustaining treatment: ethical considerations. Thorac Surg Clin. 2005. 15:469–480.

Article23. Solomon MZ. How physicians talk about futility: making words mean too many things. J Law Med Ethics. 1993. 21:231–237.

Article24. Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. Attitude and self-reported practice regarding prognostication in a national sample of internists. Arch Intern Med. 1998. 158:2389–2395.

Article25. Luce JM, White DB. The pressure to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining therapy from critically ill patients in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007. 175:1104–1108.

Article26. Anonymous . The Society of Critical Care Medicine Ethics Committee. Attitudes of critical care medicine professionals concerning distribution of intensive care resources. Crit Care Med. 1994. 22:358–362.

Article27. Society of Critical Care Medicine Ethics Committee. Consensus statement on the triage of critically ill patients. JAMA. 1994. 271:1200–1203.28. Singer DE, Carr PL, Mulley AG, Thibault GE. Rationing intensive care-physician responses to a resource shortage. N Engl J Med. 1983. 309:1155–1160.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Mediating Effects of Role Perception of Life-sustaining Treatment in the Relationship between Knowledge of Lifesustaining Treatment Plans and Attitudes toward Withdrawal of Life-sustaining Treatment among Nursing College Students

- The Effects of Nurses’ Knowledge of Withdrawal of LifeSustaining Treatment, Death Anxiety, Perceptions of Hospice on Their Attitudes toward Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Treatment

- The Relationship among Attitudes toward the Withdrawal of Life-sustaining Treatment, Death Anxiety, and Death Acceptance among Hospitalized Elderly Cancer Patients

- Awareness of Nursing Students' Biomedical Ethics and Attitudes toward Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Treatment

- Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Treatment from Children: Experiences of Nurses Caring for the Children