J Korean Med Sci.

2004 Feb;19(1):8-14. 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.1.8.

Increasing Prevalence of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium, Expanded-Spectrum Cephalosporin-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Imipenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Korea: KONSAR Study in 2001

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Laboratory Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. whonetkor@yumc.yonsei.ac.kr

- 2Department of Laboratory Medicine, College of Medicine, Chosun University, Gwangju, Korea.

- 3Department of Laboratory Medicine, Kyung Hee University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Department of Laboratory Medicine, Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center, Daegu, Korea.

- 5Department of Laboratory Medicine, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea.

- 6Pundang CHA General Hospital, Pochon CHA University, Sungnam, Korea.

- KMID: 1785686

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2004.19.1.8

Abstract

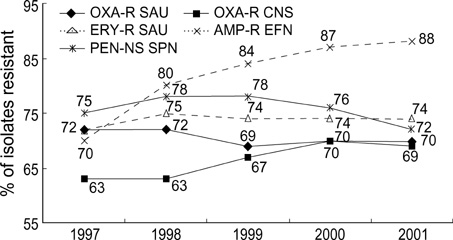

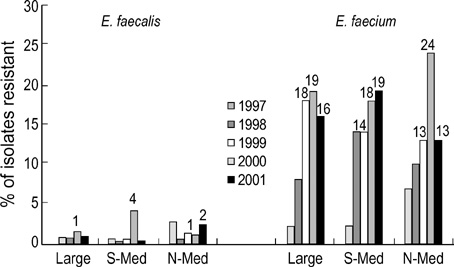

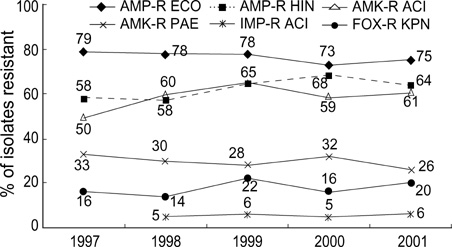

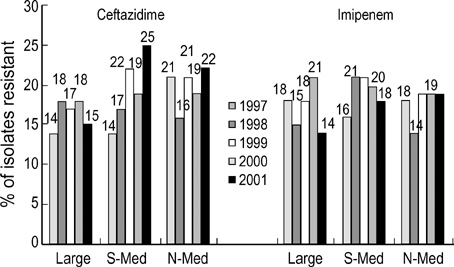

- The 5th year KONSAR surveillance in 2001 was based on routine test data at 30 participating hospitals. It was of particular interest to find a trend in the resistances of enterococci to vancomycin, of Enterobacteriaceae to the 3rd generation cephalosporin and fluoroquinolone, and of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and acinetobacters to carbapenem. Resistance rates of Gram-positive cocci were: 70% of Staphylococcus aureus to oxacillin; 88% and 16% of Enterococcus faecium to ampicillin and vancomycin, respectively. Seventy-two percent of pneumococci were nonsusceptible to penicillin. The resistance rates of Enterobacteriaceae were: Escherichia coli, 28% to fluoroquinolone; Klebsiella pneumoniae, 27% to ceftazidime, and 20% to cefoxitin; and Enterobacter cloacae, > or =40% to cefotaxime and ceftazidime. The resistance rates of P. aeruginosa were 21% to ceftazidime, 17% to imipenem, and those of the acinetobacters were > or =61% to ceftazidime, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolone and cotrimoxazole. Thirty-five percent of non-typhoidal salmonellae were ampicillin resistant, and 66% of Haemophilus influenzae were -lactamase producers. Notable changes over the 1997-2001 period were: increases in vancomycin-resistant E. faecium, and amikacin- and fluoroquinolone-resistant acinetobacters. With the increasing prevalence of resistant bacteria, nationwide surveillance has become more important for optimal patient management, for the control of nosocomial infection, and for the conservation of the newer antimicrobial agents.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 3 articles

-

Surveillance of Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance

Young Kyung Yoon, Min Ja Kim, Jang Wook Sohn, Dae Won Park, Jeong-Yeon Kim, Byung Chul Chun

Infect Chemother. 2008;40(2):93-101. doi: 10.3947/ic.2008.40.2.93.Multidrug-resistant Organisms and Healthcare-associated Infections

Mi-Na Kim

Hanyang Med Rev. 2011;31(3):141-152. doi: 10.7599/hmr.2011.31.3.141.Occurrence of a PCR-Positive but Culture-Negative Case for vanB Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci in Stool Surveillance

Dahae Won, Ki Ho Hong, Kyungah Yun, Heungsup Sung, Mi-Na Kim

Lab Med Online. 2013;3(4):264-268. doi: 10.3343/lmo.2013.3.4.264.

Reference

-

1. Hunter PA, Reeves DS. The current status of surveillance of resistance to antimicrobial agents: report on a meeting. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002. 49:17–23.

Article2. Cosgrove SE, Carmeli Y. The impact of antimicrobial resistance on health and economic outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2003. 36:1433–1437.3. Voss A, Milatovic D, Wallrauch-Schwarz C, Rosdahl VT, Braveny I. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994. 13:50–55.4. Sorberg M, Farra A, Ransjo U, Gardlund B, Rylander M, Settergren B, Kalin M, Kronvall G. Different trends in antibiotic resistance rates at a university teaching hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003. 9:388–396.5. Morris AK, Masterton RG. Antibiotic resistance surveillance: action for international studies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002. 49:7–10.

Article6. Lee K, Kim MY, Kang SH, Kang JO, Kim EC, Chong Y. KONSAR group. Korean nationwide surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in 2000 with special reference to vancomycin-resistant enterococci, and expanded-spectrum cephalosporin and imipenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli. Yonsei Med J. 2003. 44:571–578.7. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: tenth informational supplement. 2000. Wayne, PA: NCCLS.8. Fridkin SK, Hill HA, Volkova NV, Edwards JR, Lawton RM, Gaynes RP, McGowan JE Jr. Intensive Care Antimicrobial Resistance Epidemiology (ICARE) Project Hospitals. Temporal changes in prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in 23 US hospitals. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002. 8:697–701.

Article9. Bax R, Bywater R, Cornaglia G, Goossens H, Hunter P, Isham V, Jarlier V, Jones R, Phillips I, Sahm D, Senn S, Struelens M, Taylor D, White A. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance- what, how and whither? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001. 7:316–325.10. Lee K, Lee WG, Uh Y, Ha GY, Cho J, Chong Y. KONSAR Group. VIM- and IMP-type metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. in Korean hospitals. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003. 9:868–871.11. Chambers HF. Methicillin resistance in staphylococci. Molecular and biochemical basis and clinical implications. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997. 10:781–791.

Article12. Sunada A, Asari S. Report of questionnaire survey for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and penicillin resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae between 1998 and 2000 in the Kinki district. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 2003. 77:331–339.13. Sievert DM, Boulton ML, Stoltman G, Johnson D, Stobierski MG, Downes FP, Somsel PA, Rudrick JT, Brown W, Hafeezx W, Lundstrom T, Flangan E, Johnson R, Mitchell J, Chang S. Staphylococcus aureus resistant to vancomycin in United States. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. 2002. 521:565–567.14. Miller D, Urdaneta V, Weltman A. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus- Pennsylvania, 2002. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. 2002. 51:902–903.15. Bartlett JG, Breiman RF, Mandell LA, File TM Jr. Community-acquired pneumonia in adults: guidelines for management. Clin Infect Dis. 1998. 26:811–838.

Article16. Shin JW, Yong D, Kim MS, Chang KH, Lee K, Kim JM, Chong Y. Sudden increase of vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infections in a Korean tertiary care hospital: possible consequences of increased use of oral vancomycin. J Infect Chemother. 2003. 9:62–67.

Article17. Davies J. Inactivation of antibiotics and the dissemination of resistance genes. Science. 1994. 264:375–382.

Article18. Blosser-Middleton R, Sahm DF, Thornsberry C, Jones ME, Hogan PA, Critchley IA, Karlowsky JA. Antimicrobial susceptibility of 840 clinical isolates of Haemophilus influenzae collected in four European countries in 2000-2001. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003. 9:431–436.

Article19. Hasegawa K, Yamamoto K, Chiba N, Kobayashi R, Nagai K, Jacobs MR, Appelbaum PC, Sunakawa K, Ubukata K. Diversity of ampicillin-resistance genes in Haemophilus influenzae in Japan and the United States. Microb Drug Resist. 2003. 9:39–46.20. Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, Thielman NM, Slutsker L, Tauxe RV, Hennessy T, Griffin PM, DuPont H, Sack RB, Tarr P, Neill M, Nachamkin I, Reller LB, Osterholm MT, Bennish ML, Pickering LK. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2001. 32:331–351.

Article21. Lee K, Yong D, Yum JH, Kim HH, Chong Y. Diversity of TEM-52 Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates in Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003. 52:493–496.

Article22. Hooper DC. The future of the quinolones. APUA Newsletter. 2001. 19:1–5.23. Paterson DL, Ko W-C, Von Gottberg A, Casellas JM, Mulazimoglu L, Klugman KP, Bonomo RA, Rice LB, McCormack JG, Yu VL. Outcome of cephalosporin treatment for serious infections due to apparently susceptible organisms producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases: implications for clinical microbiology laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 2001. 39:2206–2212.24. Kang C, Kim S, Kim H, Park S, Choe Y, Oh M, Kim E, Choe K. The clinical outcome of blood stream infections due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: a case control study. Abstract O257. Eur Cong Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003. 9:S47.25. Bauernfeind A, Chong Y, Lee K. Plasmid-encoded AmpC β-lactamases: how far have we gone 10 years after the discovery? Yonsei Med J. 1998. 39:520–525.

Article26. Park JH, Lee SH, Jeong SH, Kim BN, Kim KB, Yoon JD, Jeon BC. Characterization and prevalence of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates producing an entended-spectrum β-lactamase from Korean hospitals. Korean J Lab Med. 2003. 23:18–24.27. Rasmussen BA, Bush K. Carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997. 41:223–232.28. Jeong SH, Lee K, Chong Y, Yum JH, Lee SH, Choi HJ, Kim JM, Park KH, Han BH, Lee SW, Jeong TS. Characterization of a new integron containing VIM-2 metallo-β-lactamase gene cassette, in a clinical isolate of Enterobacter cloacae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003. 51:397–400.29. Yum JH, Yong D, Lee K, Kim H-S, Chong Y. A new integron carrying VIM-2 metallo-beta-lactamase gene cassette in a Serratia marcescens isolate. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002. 42:217–219.30. Lee K, Lim JB, Yum JH, Yong D, Chong Y, Kim JM, Livermore DM. blaVIM-2 cassette-containing novel integrons in metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas putida isolates disseminated in a Korean hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002. 46:1053–1058.31. Joshi SG, Litake GM, Niphadkar KB, Ghole VS. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a teaching hospital. J Infect Chemother. 2003. 9:187–190.32. Munson EL, Diekema DJ, Beekmann SE, Chapin KC, Doern GV. Detection and treatment of bloodstream infection: laboratory reporting and antimicrobial management. J Clin Microbiol. 2003. 41:495–497.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- High Prevalence of Ceftazidime-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Increase of Imipenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp. in Korea: a KONSAR Program in 2004

- Increase of Ceftazidime- and Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Imipenem-Resistant Acinetobacter spp. in Korea: Analysis of KONSAR Study Data from 2005 and 2007

- Further Increase of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium, Amikacin- and Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Imipenem-Resistant Acinetobacter spp. in Korea: 2003 KONSAR Surveillance

- Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance of Bacteria in 1999 in Korea with a Special Reference to Resistance of Enterococci to Vancomycin and Gram-Negative Bacilli to Third Generation Cephalosporin, Imipenem, and Fluoroquinolone

- Korean Nationwide Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in 2000 with Special Reference to Vancomycin Resistance in Enterococci, and Expanded-Spectrum Cephalosporin and Imipenem Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacilli