J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2008 Dec;49(12):1901-1909.

Clinical Results After Application of Bevacizumab in Recurrent Pterygium

- Affiliations

-

- 1Cheil Eye Hospital, Daegu, Korea. eyepark9@dreamwiz.com

- 2Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea.

Abstract

-

PURPOSE: To clinically establish the effectiveness and safety of bevacizumab on recurrent pterygium.

METHODS

Twenty patients with recurrent pterygium were given a subconjunctival injection of 0.3 cc bevacizumab, and were evaluated for periodic clinical results at 1 week, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and every month thereafter. The patients were also evaluated for clinical results and complications.

RESULTS

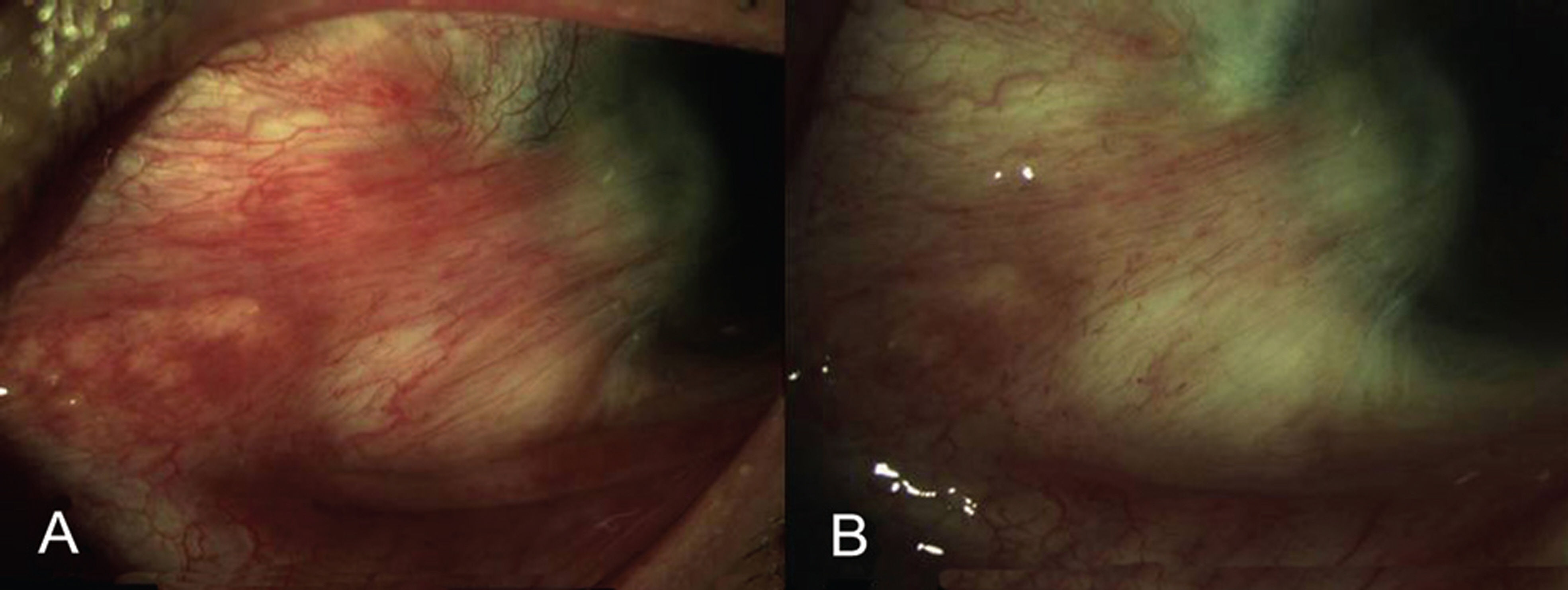

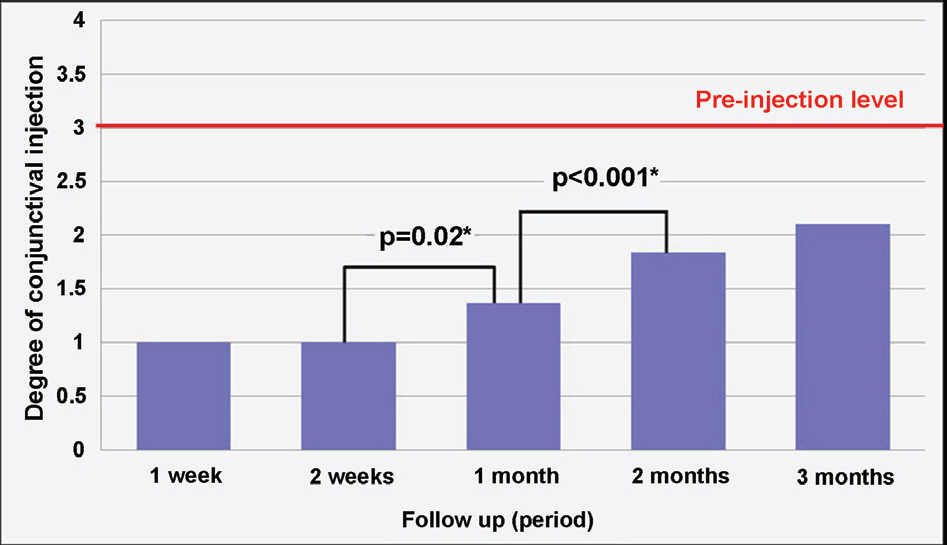

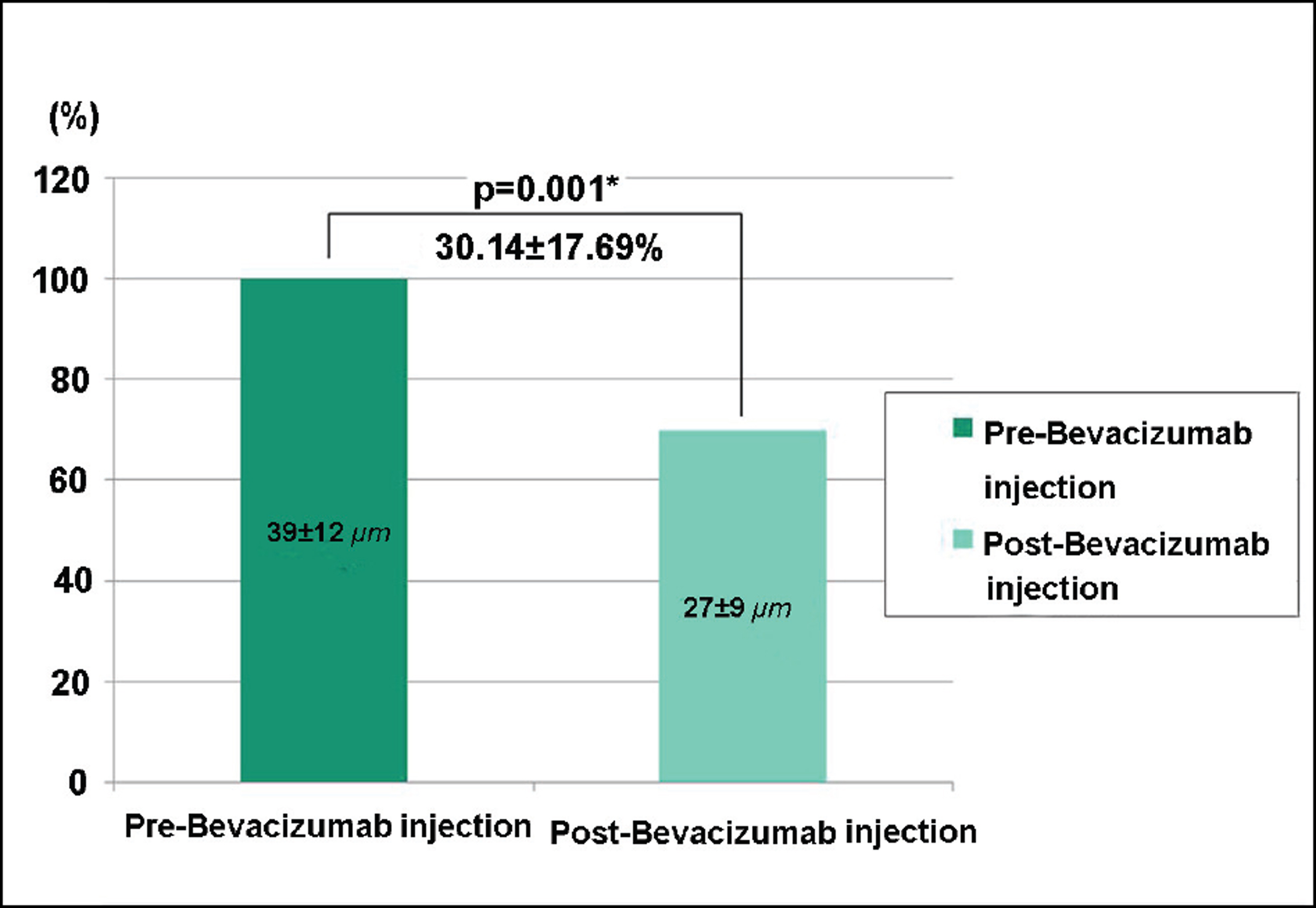

Of recurrent pterygium patients with bevacizumab injection, the conjunctival injection decreased maximally after 1 to 2 weeks, but significantly increased at 4 weeks (above the lowest level measured at 1 to 2 weeks), and no patient presented conjunctival injection above the pre-injection level at 3 months, except in 2 cases. Two weeks after the injection, ICG anterior segment angiography revealed a significant decrease (30.14+17.69%) in vessel thickness of the pterygium 2 weeks after the bevacizumab injection compared to before the injection. There had been no cases of progression of pterygium, and no ocular or systemic complications due to bevacizumab.

CONCLUSIONS

As shown above in the results, subconjunctival injection of 0.3 cc bevacizumab decreased the conjunctival injection and effectively suppressed any further progression of pterygium. Thus, bevacizumab subconjunctival injection appears to be effective in recurrent pterygium treatment instead of surgical methods.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Hill JC, Maske R. Pathogenesis of pterygium. Eye. 1989; 3:218–26.

Article2. Wong W. A hypothesis on the pathogenesis of pterygium. Ann Ophthalmol. 1978; 10:303–8.3. Coroneo MT. Pterygium as an early indicator of ultraviolet insolation: a hypothesis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993; 77:734–9.

Article4. Kria L, Ohira A, Amemiya T. Immunohisto chemical localization of basic fibroblast growth factor, platelet derived grwth factor, transforming growth factor-ß and tumor necrosis factor-α in the pterygium. Acta Histochem. 1996; 98:195–201.5. Kria L, Ohira A, Amemiya T. Growth factors in cultured pterygium fibroblasts: immunohistochemical and ELISA analysis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1998; 236:702–8.

Article6. Di Girolamo N, Coroneo MT, Wakefield D. Active matrilysin (MMP-7) in human pterygia: potential role in angiogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001; 42:1963–8.7. Lee DH, Cho HJ, Kim JT. . Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and inducible nitric oxide synthase in pterygia. Cornea. 2001; 20:738–42.

Article8. Marcovich AL, Morad Y, Sandbank J. . Angiogenesis in pterygium: morphometric and immunohistochemical study. Curr Eye Res. 2002; 25:17–22.

Article9. Aspiotis M, Tsanou E, Gorezis S. . Angiogenesis in pterygium: study of microvessel density, vascular endothelial growth factor, and thrombospondin-1. Eye. 2007; 21:1095–101.

Article10. Gebhardt M, Mentlein R, Schaudig U. . Differential expression of vascular endothelial growth factor implies the limbal origin of pterygia. Ophthalmology. 2005; 112:1023–30.

Article11. Jin J, Guan M, Sima J. . Decreased pigment epithelium- derived factor and increased vascular endothelial growth factor levels in pterygia. Cornea. 2003; 22:473–7.12. Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Novotny W. Bevacizumab (avastin), a humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody for cancer therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005; 333:328–35.

Article13. Lazic R, Gabric N. Intravitreally administered bevacizumab (avastin) in minimally classic and occult choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007; 245:68–73.14. Jorge R, Costa RA, Calucci D. . Intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) for persistent new vessels in diabetic retinopathy (IBEPE study). Retina. 2006; 26:1006–13.

Article15. Iliev ME, Domig D, Wolf-Schnurrbursch U. . Intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) in the treatment of neovascular glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006; 142:1054–6.

Article16. Manzano RP, Peyman GA, Khan P. . Inhibition of experimental corneal neovascularisation by bevacizumab (avastin). Br J Ophthalmol. 2007; 91:804–7.

Article17. DeStafeno JJ, Kim T. Topical bevacizumab therapy for corneal neovascualrization. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007; 125:834–6.18. Bock F, Onderka J, Dietrich T. . Bevacizumab as a potent inhibitior of inflammatory corneal angiogenesis and lymphangio- genesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48:2545–52.19. Hosseini H, Nejabat M. A potential therapeutic strategy for inhibition of corneal neovascularization with new anti-VEGF agents. Med Hypotheses. 2007; 68:799–801.

Article20. Sunderkotter C, Roth J, Sorg C. Immunohistochemical detection of β-FGF and TNF-α in the course of inflammatory angiogenesis in the mouse cornea. Am J Pathol. 1990; 137:511–5.21. Beck L Jr, D’Amore PA. Vascular development. cellular and molecular regulation. FASEB J. 1997; 11:365–73.

Article22. Enholm B, Paavonen K, Ristimaki A. . Comparison of VEGF, VEGF-B, VEGF-C and Ang-1 mRNA regulation by serum, growth factors, oncoproteins and hypoxia. Oncogene. 1997; 14:2475–83.

Article23. Ikeda E, Achen MG, Breier G, Risau W. Hypoxia-induced transcriptional activation and increased mRNA stability of vascular endothelial growth factor in C6 glioma cells. J Biol Chem. 1995; 270:19761–6.

Article24. Waltenberger J, Mayr U, Pentz S, Hombach V. Functional upregulation of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor KDR by hypoxia. Circulation. 1996; 94:1647–54.

Article25. Bakri SJ, Snyder MR, Reid JM. . Pharmacokinetics of intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin). Ophthalmology. 2007; 114:855–9.

Article26. Weijtens O, Feron EJ, Schoemaker RC. . High concentration of dexamethasone in aqueous and vitreous after subconjuntival injection. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999; 128:192–7.27. Matsumoto Y, Freund KB, Peiretti E. . Rebound macular edema following bevacizumab (avastin) therapy for retinal venous occlusive disease. Retina. 2007; 27:426–31.

Article28. Manzano RP, Peyman GA, Khan P. . Testing intravitreal toxicity of bevacizumab (avastin). Retina. 2006; 26:257–61.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Results After Application of Bevacizumab in Recurrent Pterygium

- Effects of Subconjunctival Bevacizumab Injection after Primary Pterygium Surgery

- The Effect of Subconjunctival Bevacizumab Injection after Primary Pterygium Surgery

- Efficacy of Subconjunctival Bevacizumab Injection after Pterygium Excision with Limbal Conjunctival Autograft in Recurred Pterygium

- Effect of Bevacizumab on Human Tenon's Fibroblasts Cultured from Primary and Recurrent Pterygium