Obstet Gynecol Sci.

2015 Nov;58(6):487-493. 10.5468/ogs.2015.58.6.487.

Contraceptive failure after hysteroscopic sterilization: Analysis of clinical and demographic data from 103 unplanned pregnancies

- Affiliations

-

- 1Reproductive Research Section, Center for Advanced Genetics, Carlsbad, CA, USA. drsills@CAGivf.com

- 2Department of Molecular & Applied Biosciences, University of Westminster, London, UK.

- 3Division of Quantitative Research, Rosenblatt Securities, Inc., New York, NY, USA.

- 4Global Health Economics Unit, Center for Clinical and Translational Science, University of Vermont College of Medicine, Burlington, VT, USA.

- 5Reproductive Sciences Medical Center, San Diego, CA, USA.

- 6Progenesis, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA.

- KMID: 2314065

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2015.58.6.487

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

This investigation examined data on unplanned pregnancies following hysteroscopic sterilization (HS).

METHODS

A confidential questionnaire was used to collect data from women with medically confirmed pregnancy (n=103) registered after undergoing HS.

RESULTS

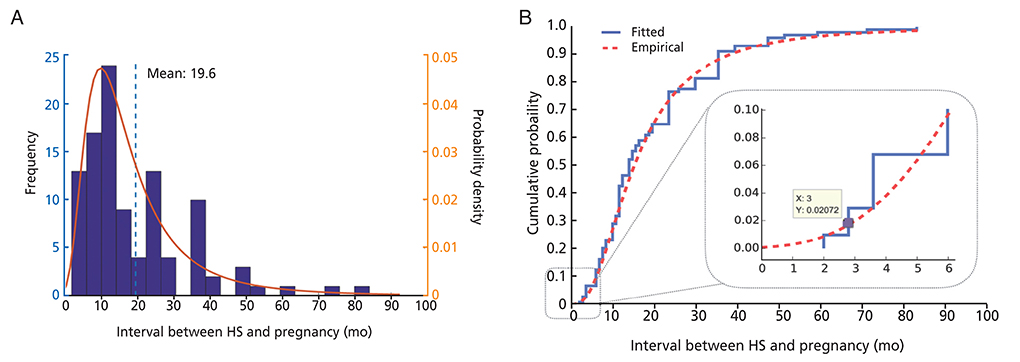

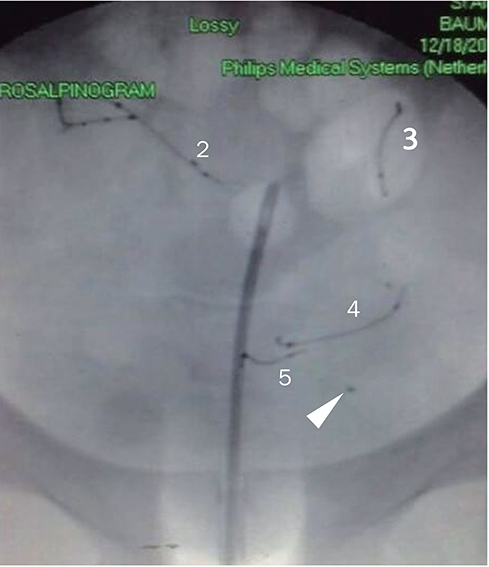

Mean (+/-SD) patient age and body mass index (BMI) were 29.5+/-4.6 years and 27.7+/-6.1 kg/m2, respectively. Peak pregnancy incidence was reported at 10 months after HS, although <3% of unplanned pregnancies occurred within the first three months following HS. Mean (+/-SD) interval between HS and pregnancy was 19.6+/-14.9 (range, 2 to 84) months. Patients age > or =30 years and BMI <25 reported conception after HS somewhat sooner than younger patients, although the differences in time to pregnancy were not significant (P=0.24 and 0.09, respectively). The recommended post-HS hysterosalpingogram (to confirm proper placement and bilateral tubal occlusion) was obtained by 66% (68/103) of respondents.

CONCLUSION

This report is the first to provide patient-derived data on contraceptive failures after HS. While adherence to backup contraception 3 months after HS can be poor, many unintended pregnancies with HS occur long after the interval when alternate contraceptive is required. Many patients who obtain HS appear to ignore the manufacturer's guidance regarding the post-procedure hysterosalpingogram to confirm proper device placement, although limited insurance coverage likely contributes to this problem. The greatest number of unplanned pregnancies occurred 10 months after HS, but some unplanned pregnancies were reported up to 7 years later. Age, BMI, or surgical history are unlikely to predict contraceptive failure with HS. Further follow-up studies are planned to capture additional data on this issue.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Jones J, Mosher W, Daniels K. Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006-2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. Natl Health Stat Report. 2012; (60):1–25.2. Podolsky ML, Desai NA, Waters TP, Nyirjesy P. Hysteroscopic tubal occlusion: sterilization after failed laparoscopic or abdominal approaches. Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 111(2 Pt 2):513–515.3. Yang R, Ma C, Qiao J, Li TC, Yang Y, Chen X, et al. The usefulness of transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy in infertile women with abnormal hysterosalpingogram results but with no obvious pelvic pathology. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011; 155:41–43.4. Kraemer DF, Yen PY, Nichols M. An economic comparison of female sterilization of hysteroscopic tubal occlusion with laparoscopic bilateral tubal ligation. Contraception. 2009; 80:254–260.5. Chapa HO, Venegas G. Preprocedure patient preferences and attitudes toward permanent contraceptive options. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012; 6:331–336.6. Yu E. Technical specifications provided by Conceptus Office of Regulatory Affairs: product information. Materials in the Essure system (ESS305). Whippany (NJ): Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals;2007.7. Lessard CR, Hopkins MR. Efficacy, safety, and patient acceptability of the Essure procedure. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011; 5:207–212.8. Ricci G, Restaino S, Di Lorenzo G, Fanfani F, Scrimin F, Mangino FP. Risk of Essure microinsert abdominal migration: case report and review of literature. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014; 10:963–968.9. Jost S, Huchon C, Legendre G, Letohic A, Fernandez H, Panel P. Essure permanent birth control effectiveness: a seven-year survey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013; 168:134–137.10. Arora P, Arora RS, Cahill D. Essure for management of hydrosalpinx prior to in vitro fertilisation-a systematic review and pooled analysis. BJOG. 2014; 121:527–536.11. Deardorff J. New study: Essure less effective than tubal ligation at preventing pregnancy. Chicago Tribune. 2014. 04. 21. Sect. A. 2.12. Gariepy AM, Creinin MD, Smith KJ, Xu X. Probability of pregnancy after sterilization: a comparison of hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic sterilization. Contraception. 2014; 90:174–181.13. Catallo H. Fifth death associated with controversial Essure birth control implant [Internet]. Southfield (MI): WXYZ Detroit;2014. cited 2015 Sep 30. Available from: http://www.wxyz.com/news/local-news/investigations/fifth-death-associated-with-controversial-essure-birthcontrol-implant.14. Kotz S, Nadarajah S. Extreme value distributions: theory and applications. London: Imperial College Press;2000.15. Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011; 83:397–404.16. Leyser-Whalen O, Berenson AB. Adherence to hysterosalpingogram appointments following hysteroscopic sterilization among low-income women. Contraception. 2013; 88:697–699.17. Kerin JF, Cooper JM, Price T, Herendael BJ, Cayuela-Font E, Cher D, et al. Hysteroscopic sterilization using a microinsert device: results of a multicentre Phase II study. Hum Reprod. 2003; 18:1223–1230.18. Savage UK, Masters SJ, Smid MC, Hung YY, Jacobson GF. Hysteroscopic sterilization in a large group practice: experience and effectiveness. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114:1227–1231.19. Shavell VI, Abdallah ME, Diamond MP, Kmak DC, Berman JM. Post-Essure hysterosalpingography compliance in a clinic population. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008; 15:431–434.20. Guiahi M, Goldman KN, McElhinney MM, Olson CG. Improving hysterosalpingogram confirmatory test follow-up after Essure hysteroscopic sterilization. Contraception. 2010; 81:520–524.21. Anderson TL, Yunker AC, Scheib SA, Callahan TL. Hysteroscopic sterilization success in outpatient vs office setting is not affected by patient or procedural characteristics. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013; 20:858–863.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Contraceptive failure after hysteroscopic sterilization: Analysis of clinical and demographic data from 103 unplanned pregnancies

- Postcoital Contraceptive Pills

- Sociomedical Study on the Person Recieved Permanent Sterilization Method in Busan Area

- Pregnancy and Childbirth Experience of Unmarried Teenage Mothers

- Voluntary Sterilization in Rural Korea