J Korean Med Sci.

2024 Jan;39(4):e37. 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e37.

The Risk of COVID-19 and Its Outcomes in Korean Patients With Gout: A Multicenter, Retrospective, Observational Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Hospital Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 2Center for Data Science, Biomedical Research Institute, Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Hospital Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 3Biomedical Research Institute, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Transdisciplinary Medicine, Institute of Convergence Medicine with Innovative Technology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 5Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2551967

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e37

Abstract

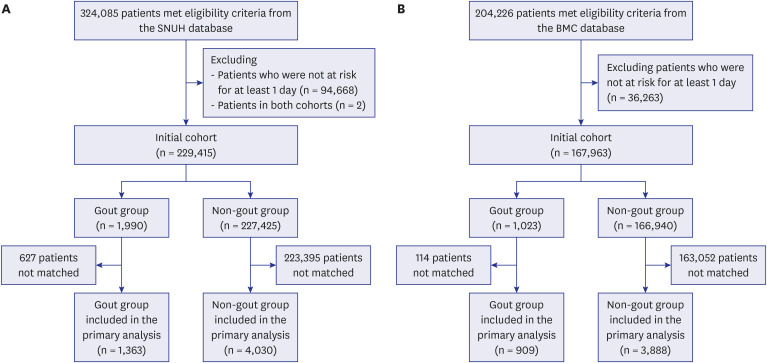

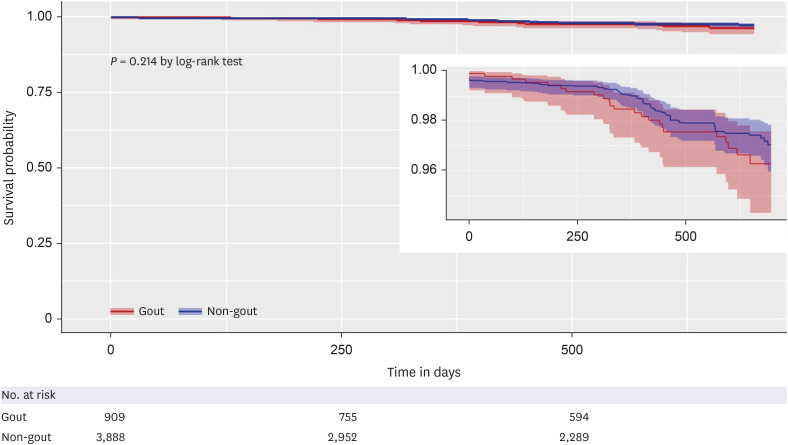

- This retrospective cohort study aimed to compare coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related clinical outcomes between patients with and without gout. Electronic health recordbased data from two centers (Seoul National University Hospital [SNUH] and Boramae Medical Center [BMC]), from January 2021 to April 2022, were mapped to a common data model. Patients with and without gout were matched using a large-scale propensityscore algorithm based on population-level estimation methods. At the SNUH, the risk for COVID-19 diagnosis was not significantly different between patients with and without gout (hazard ratio [HR], 1.07; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.59–1.84). Within 30 days after COVID-19 diagnosis, no significant difference was observed in terms of hospitalization (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.03–3.90), severe outcomes (HR, 2.90; 95% CI, 0.54–13.71), or mortality (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 0.06–16.24). Similar results were obtained from the BMC database, suggesting that gout does not increase the risk for COVID-19 diagnosis or severe outcomes.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Shin YH, Shin JI, Moon SY, Jin HY, Kim SY, Yang JM, et al. Autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases and COVID-19 outcomes in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021; 3(10):e698–e706. PMID: 34179832.2. Roddy E, Doherty M. Epidemiology of gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010; 12(6):223. PMID: 21205285.3. Topless RK, Gaffo A, Stamp LK, Robinson PC, Dalbeth N, Merriman TR. Gout and the risk of COVID-19 diagnosis and death in the UK Biobank: a population-based study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2022; 4(4):e274–e281. PMID: 35128470.4. Xie D, Choi HK, Dalbeth N, Wallace ZS, Sparks JA, Lu N, et al. Gout and excess risk of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection among vaccinated individuals: a general population study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023; 75(1):122–132. PMID: 36082457.5. Jatuworapruk K, Montgomery A, Gianfrancesco M, Conway R, Durcan L, Graef ER, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of people with gout hospitalized due to COVID-19: data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance Physician-reported registry. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2022; 4(11):948–953. PMID: 36000538.6. Tai V, Robinson PC, Dalbeth N. Gout and the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2022; 34(2):111–117. PMID: 34907115.7. Tian Y, Schuemie MJ, Suchard MA. Evaluating large-scale propensity score performance through real-world and synthetic data experiments. Int J Epidemiol. 2018; 47(6):2005–2014. PMID: 29939268.8. Choi HK, McCormick N, Yokose C. Excess comorbidities in gout: the causal paradigm and pleiotropic approaches to care. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022; 18(2):97–111. PMID: 34921301.9. Peng H, Wu X, Xiong S, Li C, Zhong R, He J, et al. Gout and susceptibility and severity of COVID-19: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization analysis. J Infect. 2022; 85(3):e59–e61. PMID: 35724757.10. Crișan TO, Cleophas MC, Oosting M, Lemmers H, Toenhake-Dijkstra H, Netea MG, et al. Soluble uric acid primes TLR-induced proinflammatory cytokine production by human primary cells via inhibition of IL-1Ra. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016; 75(4):755–762. PMID: 25649144.11. Tanaka T, Milaneschi Y, Zhang Y, Becker KG, Zukley L, Ferrucci L. A double blind placebo controlled randomized trial of the effect of acute uric acid changes on inflammatory markers in humans: a pilot study. PLoS One. 2017; 12(8):e0181100. PMID: 28786993.12. Conway R, Nikiphorou E, Demetriou CA, Low C, Leamy K, Ryan JG, et al. Temporal trends in COVID-19 outcomes in people with rheumatic diseases in Ireland: data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance registry. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022; 61(SI2):SI151–SI156. PMID: 35258593.13. Tabatabai M, Juarez PD, Matthews-Juarez P, Wilus DM, Ramesh A, Alcendor DJ, et al. An analysis of COVID-19 mortality during the dominancy of alpha, delta, and omicron in the USA. J Prim Care Community Health. 2023; 14:21501319231170164. PMID: 37083205.14. Yasmin F, Najeeb H, Moeed A, Naeem U, Asghar MS, Chughtai NU, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the United States: a systematic review. Front Public Health. 2021; 9:770985. PMID: 34888288.15. Moraliyska R, Georgiev T, Bogdanova-Petrova S, Shivacheva T. Adoption rates of recommended vaccines and influencing factors among patients with inflammatory arthritis: a patient survey. Rheumatol Int. Forthcoming. 2023; DOI: 10.1007/s00296-023-05476-2.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- COVID-19 and Cancer: Questions to Be Answered

- Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors and COVID-19-Related Deaths among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies

- The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on in-hospital mortality in patients admitted through the emergency department

- Infection prevention measures and outcomes for surgical patients during a COVID-19 outbreak in a tertiary hospital in Daegu, South Korea: a retrospective observational study

- Impact of COVID-19 infection during the postoperative period in patients who underwent gastrointestinal surgery: a retrospective study