J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Sep;38(37):e284. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e284.

Self-Esteem Trajectories After Occupational Injuries and Diseases and Their Relation to Changes in Subjective Health: Result From the Panel Study of Workers’ Compensation Insurance (PSWCI)

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2The Institute for Occupational Health, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Graduate School, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Public Health, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2546199

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e284

Abstract

- Background

Occupational injuries and diseases are life events that significantly impact an individuals’ identity. In this study, we examined the trajectories of self-esteem among victims of occupational injury and disease and their relation to health.

Methods

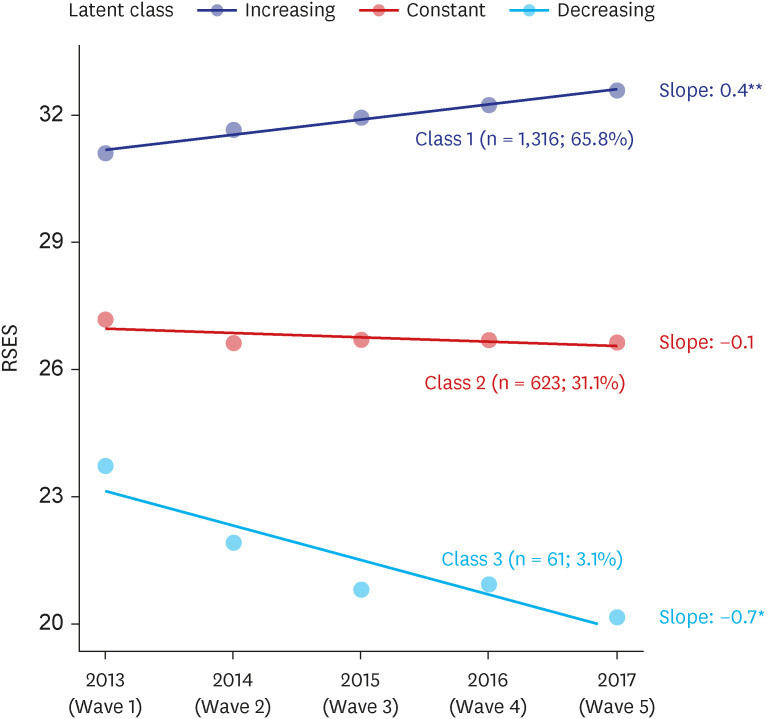

The Panel Study of Workers’ Compensation Insurance conducted annual followups on workers who had experienced occupational injury or disease. A total of 2,000 participants, who had completed medical care, were followed from 2013 to 2017. Growth mixture modeling was utilized to identify latent classes in the self-esteem trajectory. Additionally, logistic regressions were conducted to explore the association between trajectory membership, baseline predictors, and outcomes.

Results

Three distinct trajectory classes were identified. Total 65.8% of the samples (n = 1,316) followed an increasing self-esteem trajectory, while 31.1% (n = 623) exhibited a constant trajectory, and 3.1% (n = 61) showed a decreasing trajectory. Individuals with an increasing trajectory were more likely to have a higher educational attainment (odds ratio [OR], 1.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20–2.88), an absence of a moderate-to-severe disability rating (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.25–0.96), no difficulty in daily living activities (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.75–0.88), and were economically active (re-employed: OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.52–3.98; returned to original work: OR, 4.46; 9% CI, 2.65–7.50). Those with a decreasing self-esteem trajectory exhibited an increased risk of poor subjective health (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 0.85–4.85 in 2013 to OR, 3.17; 95% CI, 1.04–13.81 in 2017), whereas individuals with an increasing trajectory showed a decreased risk (OR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.43–0.68 in 2013 to OR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.33–0.57 in 2017).

Conclusion

Our findings emphasize the diversity of psychological responses to occupational injury or disease. Policymakers should implement interventions to enhance the self-esteem of victims.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Cha EW, Jung SM, Lee IH, Kim DH, Choi EH, Kim IA, et al. Approval status and characteristics of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among Korean workers in 2020. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2022; 34(1):e31. PMID: 36452248.

Article2. Kim UJ, Choi WJ, Kang SK, Lee W, Ham S, Lee J, et al. Standards for recognition and approval rate of occupational cerebro-cardiovascular diseases in Korea. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2022; 34(1):e30. PMID: 36452249.3. GBD 2016 Occupational Risk Factors Collaborators. Global and regional burden of disease and injury in 2016 arising from occupational exposures: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Occup Environ Med. 2020; 77(3):133–141. PMID: 32054817.4. Leigh JP. Economic burden of occupational injury and illness in the United States. Milbank Q. 2011; 89(4):728–772. PMID: 22188353.5. Stoesz B, Chimney K, Deng C, Grogan H, Menec V, Piotrowski C, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of non-fatal work-related injuries among older workers: a review of research from 2010 to 2019. Saf Sci. 2020; 126:126.6. Won Y, Kim HC, Kim J, Kim M, Yang SC, Park SG, et al. Impacts of presenteeism on work-related injury absence and disease absence. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2022; 34(1):e25. PMID: 36267359.7. Lee WT, Lim SS, Kim MS, Baek SU, Yoon JH, Won JU. Analyzing decline in quality of life by examining employment status changes of occupationally injured workers post medical care. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2022; 34(1):e17. PMID: 36093268.

Article8. Chin WS, Guo YL, Liao SC, Wu HC, Kuo CY, Chen CC, et al. Quality of life at 6 years after occupational injury. Qual Life Res. 2018; 27(3):609–618. PMID: 29288434.

Article9. Lee KS, Joo SY, Seo CH, Park JE, Lee BC. Work-related burn injuries and claims for post-traumatic stress disorder in Korea. Burns. 2019; 45(2):461–465. PMID: 30718028.10. Lin KH, Guo NW, Liao SC, Kuo CY, Hu PY, Hsu JH, et al. Psychological outcome of injured workers at 3 months after occupational injury requiring hospitalization in Taiwan. J Occup Health. 2012; 54(4):289–298. PMID: 22672883.11. Salah Eldin W, Hirshon JM, Smith GS, Kamal AA, Abou-El-Fetouh A, El-Setouhy M. Health-related quality of life after serious occupational injury in Egyptian workers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2012; 2(6):e000413.12. Dentale F, Vecchione M, Alessandri G, Barbaranelli C. Investigating the protective role of global self-esteem on the relationship between stressful life events and depression: a longitudinal moderated regression model. Curr Psychol. 2020; 39(6):2096–2107.13. Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, Vohs KD. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2003; 4(1):1–44. PMID: 26151640.

Article14. Choi Y, Choi SH, Yun JY, Lim JA, Kwon Y, Lee HY, et al. The relationship between levels of self-esteem and the development of depression in young adults with mild depressive symptoms. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019; 98(42):e17518. PMID: 31626112.

Article15. Arsandaux J, Michel G, Tournier M, Tzourio C, Galéra C. Is self-esteem associated with self-rated health among French college students? A longitudinal epidemiological study: the i-Share cohort. BMJ Open. 2019; 9(6):e024500.

Article16. Beadle EJ, Ownsworth T, Fleming J, Shum D. The impact of traumatic brain injury on self-identity: a systematic review of the evidence for self-concept changes. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2016; 31(2):E12–E25.17. Lax MB, Klein R. More than meets the eye: social, economic, and emotional impacts of work-related injury and illness. New Solut. 2008; 18(3):343–360. PMID: 19058415.

Article18. Mund M, Neyer FJ. Rising high or falling deep? Pathways of self–esteem in a representative German sample. Eur J Pers. 2016; 30(4):341–357.

Article19. Reitz AK. Self-esteem development and life events: a review and integrative process framework. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2022; 16(11):e12709.

Article20. Rosenberg M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Washington, D.C., USA: American Psychological Association;1965.21. Bae HN, Choi SW, Yu JC, Lee JS. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (K-RSES) in adult. Mood Emot. 2014; 12(1):43–49.22. Muthén B, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000; 24(6):882–891. PMID: 10888079.

Article23. Wickrama KK, Lee TK, O'Neal CW, Lorenz FO. Higher-Order Growth Curves and Mixture Modeling With Mplus. New York, NY, USA: Routledge;2016.24. Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using M plus. Struct Equ Modeling. 2014; 21(3):329–341.

Article25. Clark SL. Mixture Modeling With Behavioral Data. Los Angeles, CA, USA: University of California;2010.26. Jung T, Wickrama KA. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2008; 2(1):302–317.

Article27. Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Modeling. 2007; 14(4):535–569.

Article28. Lin KH, Shiao JS, Guo NW, Liao SC, Kuo CY, Hu PY, et al. Long-term psychological outcome of workers after occupational injury: prevalence and risk factors. J Occup Rehabil. 2014; 24(1):1–10. PMID: 23504486.

Article29. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq. 2004; 15(1):1–18.30. Grunert BK, Devine CA, Matloub HS, Sanger JR, Yousif NJ, Anderson RC, et al. Psychological adjustment following work-related hand injury: 18-month follow-up. Ann Plast Surg. 1992; 29(6):537–542. PMID: 1466550.31. Quale AJ, Schanke AK. Resilience in the face of coping with a severe physical injury: a study of trajectories of adjustment in a rehabilitation setting. Rehabil Psychol. 2010; 55(1):12–22. PMID: 20175630.

Article32. Bonanno GA, Kennedy P, Galatzer-Levy IR, Lude P, Elfström ML. Trajectories of resilience, depression, and anxiety following spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2012; 57(3):236–247. PMID: 22946611.

Article33. Klinge K, Chamberlain DJ, Redden M, King L. Psychological adjustments made by postburn injury patients: an integrative literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2009; 65(11):2274–2292. PMID: 19832748.

Article34. deRoon-Cassini TA, Mancini AD, Rusch MD, Bonanno GA. Psychopathology and resilience following traumatic injury: a latent growth mixture model analysis. Rehabil Psychol. 2010; 55(1):1–11. PMID: 20175629.

Article35. Thombs BD, Notes LD, Lawrence JW, Magyar-Russell G, Bresnick MG, Fauerbach JA. From survival to socialization: a longitudinal study of body image in survivors of severe burn injury. J Psychosom Res. 2008; 64(2):205–212. PMID: 18222134.

Article36. Mann M, Hosman CM, Schaalma HP, de Vries NK. Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion. Health Educ Res. 2004; 19(4):357–372. PMID: 15199011.

Article37. Jeong I, Yoon JH, Roh J, Rhie J, Won JU. Association between the return-to-work hierarchy and self-rated health, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2019; 92(5):709–716. PMID: 30758655.

Article38. Rasmussen DM, Elverdam B. The meaning of work and working life after cancer: an interview study. Psychooncology. 2008; 17(12):1232–1238. PMID: 18623607.

Article39. Cullen KL, Irvin E, Collie A, Clay F, Gensby U, Jennings PA, et al. Effectiveness of workplace interventions in return-to-work for musculoskeletal, pain-related and mental health conditions: an update of the evidence and messages for practitioners. J Occup Rehabil. 2018; 28(1):1–15. PMID: 28224415.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Workers' Compensation Insurance and Occupational Injuries

- Work-Related Musculoskeletal Diseases and the Workers' Compensation

- Recent Changes to Improve the Process of Compensation of Occupational Diseases in Workers Covered by the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act

- Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases in Special Populations: Farmers and Soldiers

- Occupational Diseases and Injuries among Korean Nurses