J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Jun;38(22):e171. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e171.

Decrease in Weekly Working Hours of Korean Workers From 2010 to 2020 According to Employment Status and Industrial Sector

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Occupational Health, The Catholic University of Daegu, Gyeongsan, Korea

- 2Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Ulsan University Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Ulsan, Korea

- KMID: 2542803

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e171

Abstract

- Background

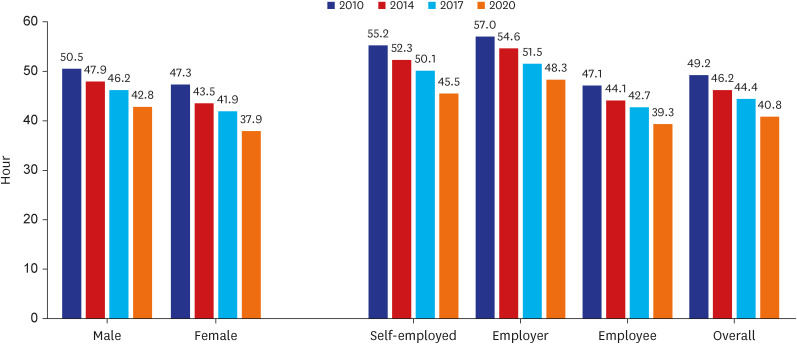

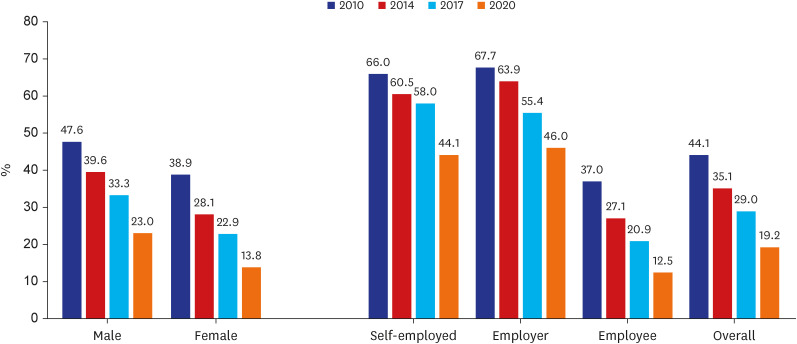

The present study examined changes in the working hours of Korean workers from 2010 to 2020 according to employment status and industrial sector.

Methods

This was a secondary analysis of data from the third (2010), fourth (2014), fifth (2017) and sixth (2020) Korean Working Conditions Surveys, which were conducted by the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency.

Results

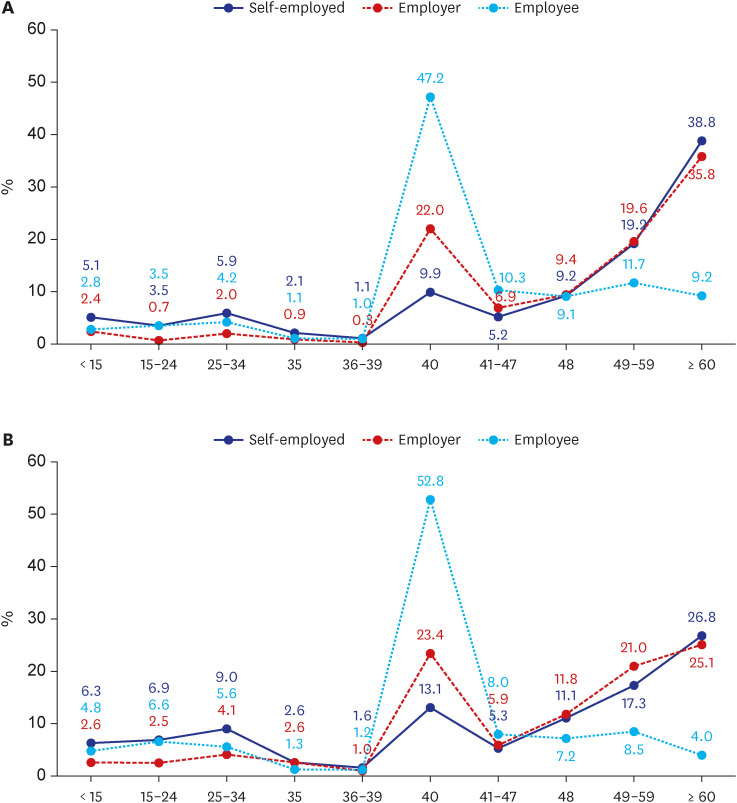

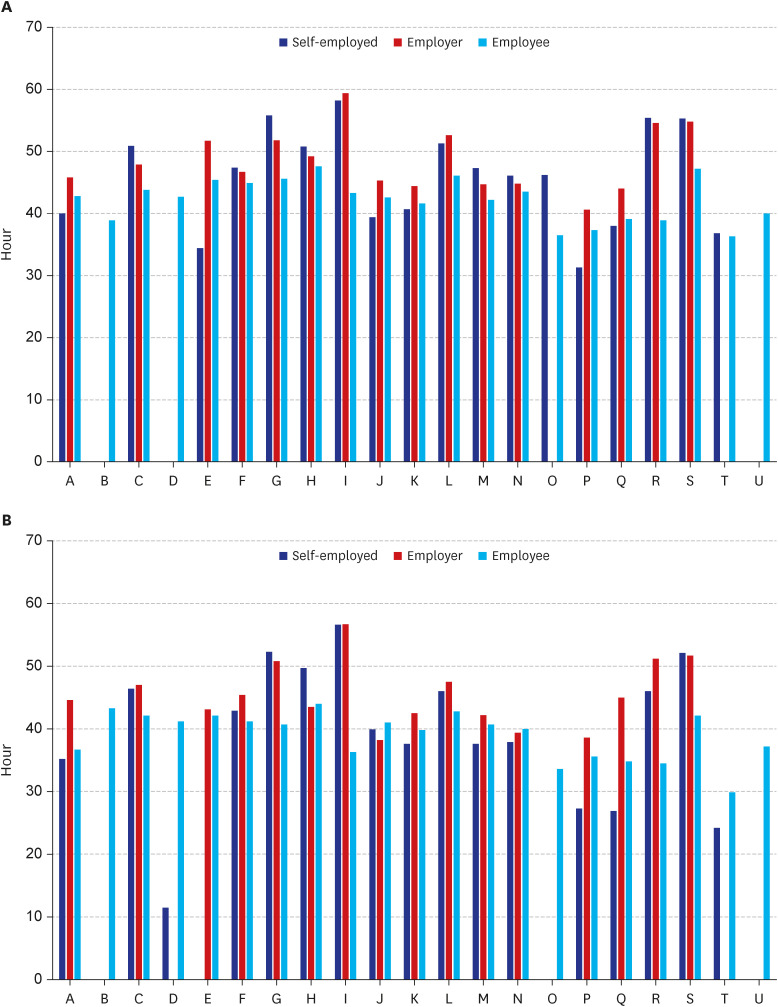

During the past 10 years, workers classified as employees, self-employed, or employers experienced clear declines in average weekly working hours and in the percentages of individuals who worked more than 48 hours per week. During 2020, the largest proportion of employees (52.8%) had 40-hour work weeks, whereas the largest proportions of selfemployed individuals (26.8%) and employers (25.1%) had very long work weeks (≥ 60 h/ week). Also during 2020, individuals who were self-employed or employers in the sectors of ‘Accommodation and food service’ had the longest weekly work hours, whereas employees in the sector of ‘Transportation’ had the longest weekly work hours. All three groups (employees, self-employed, and employers) in all 21 industrial sectors experienced declines in average weekly working hours from 2017 to 2020.

Conclusion

From 2010 to 2020, employees, self-employed individuals, and employers experienced clear declines in average weekly working hours, and in the percentages of individuals with long weekly working hours. However, there were also differences in the weekly working hours of those who had different employment status and who worked in different industrial sectors. The implementation of the 40-hour work-week and the 52-hour maximum work-week in Korea reduced excessive work hours by individuals who had different employment status and who worked in different industrial sectors, and probably improved worker quality-of-life. We recommend extension of these regulations to workplaces with fewer than 5 employees.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Statistics 2021. Paris, France: OECD;2021.2. Park J, Yi Y, Kim Y. Weekly work hours and stress complaints of workers in Korea. Am J Ind Med. 2010; 53(11):1135–1141. PMID: 20665532.

Article3. International Labour Organization (ILO). Working Time: Its Impact on Safety and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: ILO;2003.4. Härmä M. Workhours in relation to work stress, recovery and health. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006; 32(6):502–514. PMID: 17173206.

Article5. Park J, Kim Y, Han B. Long working hours in Korea: based on the 2014 Korean Working Conditions Survey. Saf Health Work. 2017; 8(4):343–346. PMID: 29276632.

Article6. Park J, Kwon OJ, Kim Y. Long working hours in Korea: results of the 2010 Working Conditions Survey. Ind Health. 2012; 50(5):458–462. PMID: 22878357.7. Ministry of Employment and Labor. Labor Standards Act. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Government Legislation;2011.8. Ministry of Employment and Labor. Labor Standards Act. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Government Legislation;2018.9. Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency. Korean Working Conditions Survey. Ulsan, Korea: Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency;2016.10. Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency. The Fifth Korean Working Conditions Survey. Ulsan, Korea: Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency;2019.11. Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency. The Sixth Korean Working Conditions Survey. Ulsan, Korea: Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency;2021.12. Park J, Lee N. First Korean Working Conditions Survey: a comparison between South Korea and EU countries. Ind Health. 2009; 47(1):50–54. PMID: 19218757.

Article13. Lee S, McCann D, Messenger JC. Working Time Around the World: Trends in Working Hours, Laws, and Policies in a Global Comparative Perspective. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization;2007.14. Descatha A, Sembajwe G, Pega F, Ujita Y, Baer M, Boccuni F, et al. The effect of exposure to long working hours on stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int. 2020; 142:105746. PMID: 32505015.

Article15. Li J, Pega F, Ujita Y, Brisson C, Clays E, Descatha A, et al. The effect of exposure to long working hours on ischaemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int. 2020; 142:105739. PMID: 32505014.

Article16. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Labour statistics. Updated 2022. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://www.oecd.org/sdd/labour-stats/ .17. Urzi Brancati MC, Pesole A, Fernández Macías E. New Evidence on Platform Workers in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union;2020.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Employment Factors Associated With Long Working Hours in France

- Relationship Between Long Working Hours and Metabolic Syndrome Among Korean Workers

- The Relationship between Long Working Hours and Industrial Accident

- Factors associated with health-related quality of life in Korean older workers

- Association between employment status and self-rated health: Korean working conditions survey