J Korean Neurosurg Soc.

2023 May;66(3):239-246. 10.3340/jkns.2022.0277.

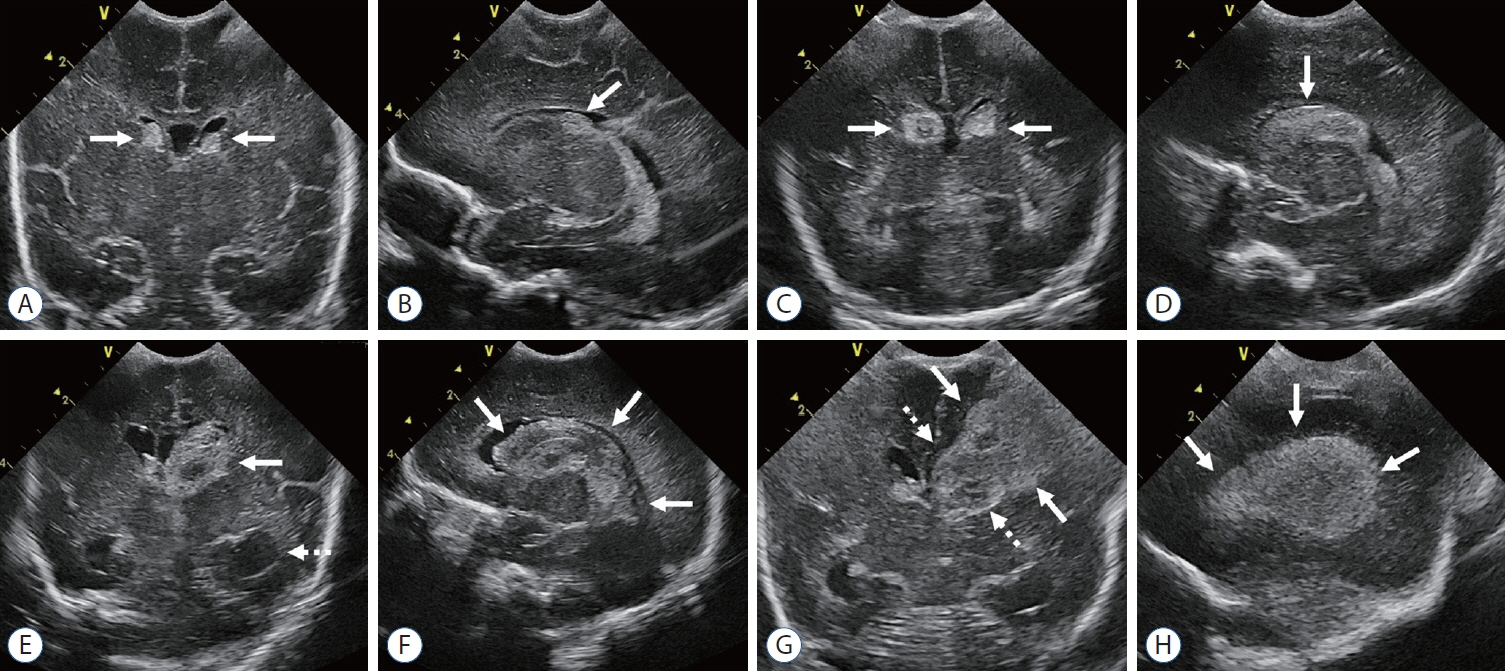

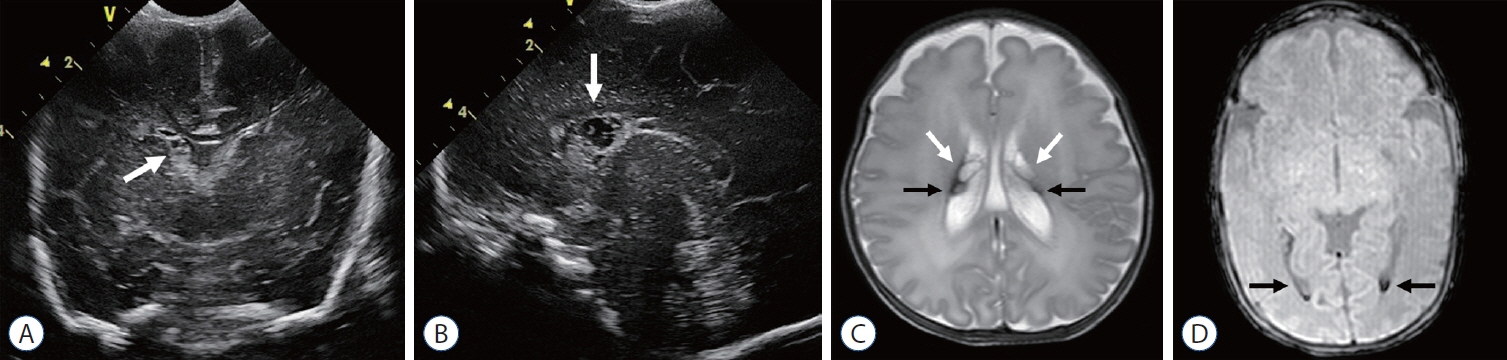

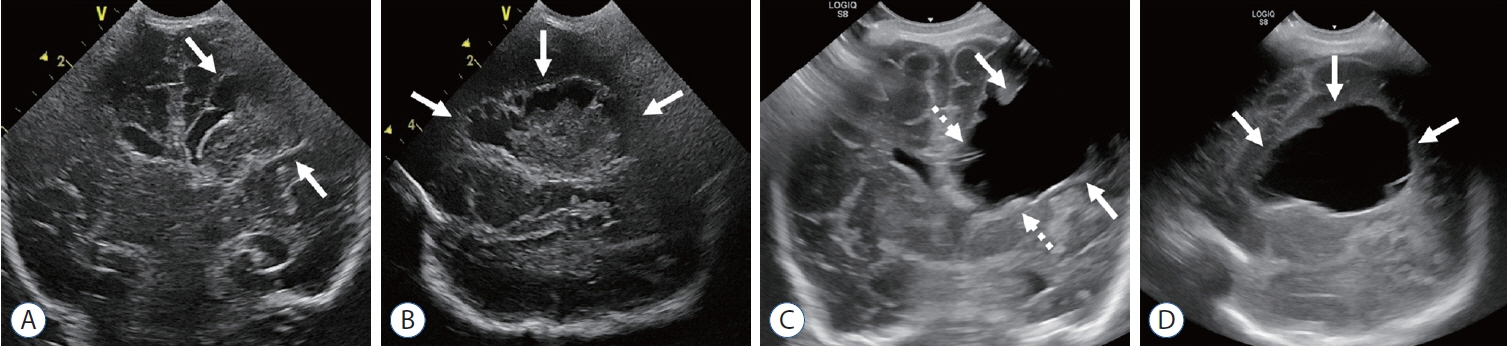

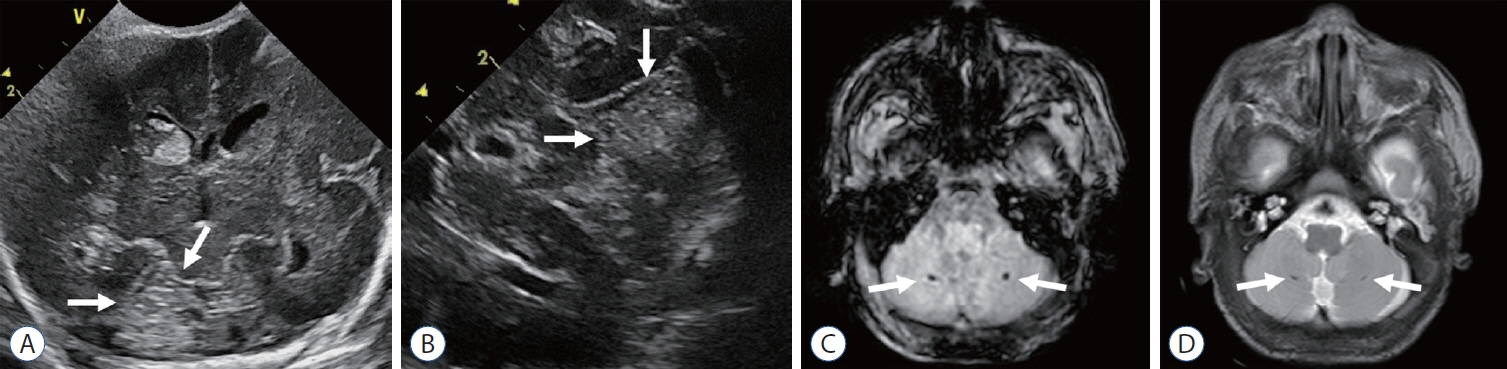

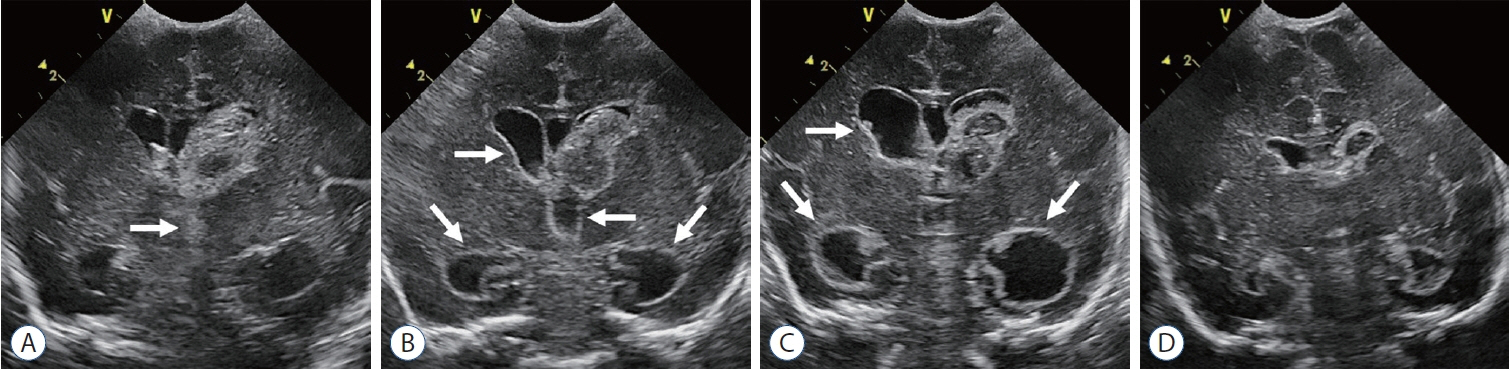

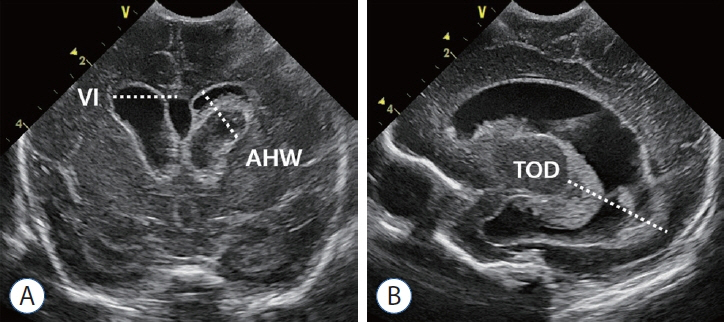

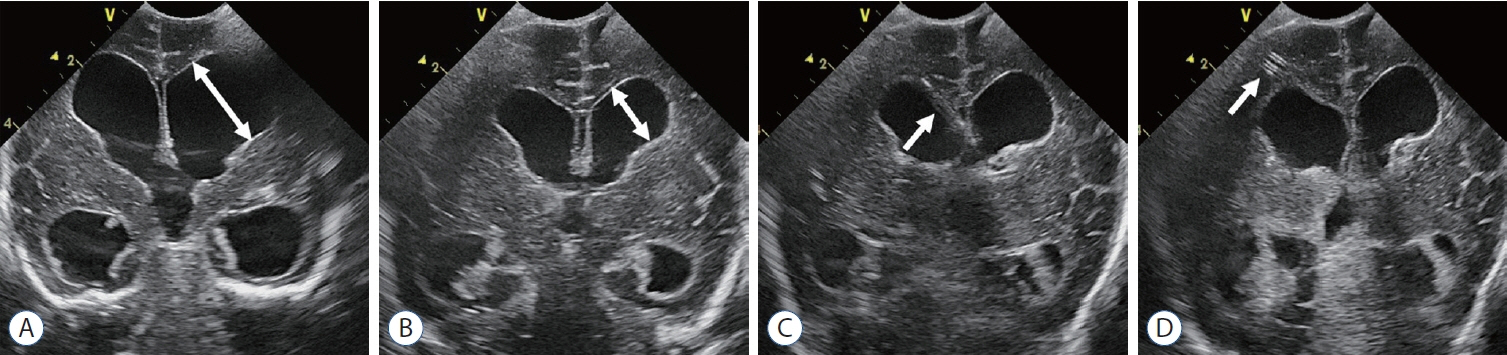

Neuroimaging of Germinal Matrix and Intraventricular Hemorrhage in Premature Infants

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Radiology, Chungnam National University Hospital, Chungnam National University College of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea

- KMID: 2542008

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2022.0277

Abstract

- Germinal matrix and intraventricular hemorrhage (GM-IVH) are the major causes of intracranial hemorrhage in premature infants. Cranial ultrasound (cUS) is the imaging modality of choice for diagnosing and classifying GM-IVH. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), usually performed at term-equivalent age, is more sensitive than cUS in identifying hemorrhage in the brain. Post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilatation is a significant complication of GM-IVH and correlates with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. In this review, we discuss the various imaging findings of GM-IVH in premature infants, focusing on the role of cUS and MRI.

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Editor’s Pick in May 2023

Chae-Yong Kim, Seung-Ki Kim

J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2023;66(3):223-224. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2023.0079.

Reference

-

References

1. Arulkumaran S, Tusor N, Chew A, Falconer S, Kennea N, Nongena P, et al. MRI findings at term-corrected age and neurodevelopmental outcomes in a large cohort of very preterm infants. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 41:1509–1516. 2020.

Article2. Brouwer MJ, de Vries LS, Pistorius L, Rademaker KJ, Groenendaal F, Benders MJ. Ultrasound measurements of the lateral ventricles in neonates: why, how and when? A systematic review. Acta Paediatr. 99:1298–1306. 2010.

Article3. Brouwer MJ, de Vries LS, Groenendaal F, Koopman C, Pistorius LR, Mulder EJ, et al. New reference values for the neonatal cerebral ventricles. Radiology. 262:224–233. 2012.

Article4. Camfferman FA, de Goederen R, Govaert P, Dudink J, van Bel F, Pellicer A, et al. Diagnostic and predictive value of Doppler ultrasound for evaluation of the brain circulation in preterm infants: a systematic review. Pediatr Res. 87(Suppl 1):50–58. 2020.

Article5. Cizmeci MN, Khalili N, Claessens NHP, Groenendaal F, Liem KD, Heep A, et al. Assessment of brain injury and brain volumes after posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation: a nested substudy of the randomized controlled ELVIS trial. J Pediatr. 208:191–197.e2. 2019.

Article6. Cizmeci MN, Groenendaal F, Liem KD, van Haastert IC, BenaventeFernández I, van Straaten HLM, et al. Randomized controlled early versus late ventricular intervention study in posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation: outcome at 2 years. J Pediatr. 226:28–35.e3. 2020.7. Çizmeci MN, Akın MA, Özek E. Turkish neonatal society guideline on the diagnosis and management of germinal matrix hemorrhage-intraventricular hemorrhage and related complications. Turk Arch Pediatr. 56:499–512. 2021.8. Coley BD. Caffey’s pediatric diagnostic imaging E-book, ed 13. Philadelphia: Elsevier - OHCE;2018. p. 257.9. Dorner RA, Burton VJ, Allen MC, Robinson S, Soares BP. Preterm neuroimaging and neurodevelopmental outcome: a focus on intraventricular hemorrhage, post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus, and associated brain injury. J Perinatol. 38:1431–1443. 2018.

Article10. El-Dib M, Limbrick DD Jr, Inder T, Whitelaw A, Kulkarni AV, Warf B, et al. Management of post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilatation in the infant born preterm. J Pediatr. 226:16–27.e3. 2020.11. Gaisie G, Roberts MS, Bouldin TW, Scatliff JH. The echogenic ependymal wall in intraventricular hemorrhage: sonographic-pathologic correlation. Pediatr Radiol. 20:297–300. 1990.

Article12. George JM, Fiori S, Fripp J, Pannek K, Bursle J, Moldrich RX, et al. Validation of an MRI brain injury and growth scoring system in very preterm infants scanned at 29- to 35-week postmenstrual age. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 38:1435–1442. 2017.

Article13. Guillot M, Chau V, Lemyre B. Routine imaging of the preterm neonatal brain. Paediatr Child Health. 25:249–255. 2020.

Article14. Guillot M, Sebastianski M, Lemyre B. Comparative performance of head ultrasound and MRI in detecting preterm brain injury and predicting outcomes: a systematic review. Acta Paediatr. 110:1425–1432. 2021.

Article15. Hand IL, Shellhaas RA, Milla SS; Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neurology, Section on Radiology. Routine neuroimaging of the preterm brain. Pediatrics. 146:e2020029082. 2020.

Article16. Intrapiromkul J, Northington F, Huisman TA, Izbudak I, Meoded A, Tekes A. Accuracy of head ultrasound for the detection of intracranial hemorrhage in preterm neonates: comparison with brain MRI and susceptibility-weighted imaging. J Neuroradiol. 40:81–88. 2013.

Article17. Jhaveri MD. Diagnostic Imaging: Brain E-Book, ed 4. Philadelphia: Elsevier - OHCE;2020. p. 271–274.18. Kidokoro H, Neil JJ, Inder TE. New MR imaging assessment tool to define brain abnormalities in very preterm infants at term. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 34:2208–2214. 2013.

Article19. Leijser LM, Scott JN, Roychoudhury S, Zein H, Murthy P, Thomas SP, et al. Post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilatation: inter-observer reliability of ventricular size measurements in extremely preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 90:403–410. 2021.

Article20. Lowe LH, Bailey Z. State-of-the-art cranial sonography: part 2, pitfalls and variants. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 196:1034–1039. 2011.

Article21. Lowe LH, Bailey Z. State-of-the-art cranial sonography: part 1, modern techniques and image interpretation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 196:1028–1033. 2011.

Article22. Ment LR, Bada HS, Barnes P, Grant PE, Hirtz D, Papile LA, et al. Practice parameter: neuroimaging of the neonate: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 58:1726–1738. 2002.

Article23. Nataraj P, Svojsik M, Sura L, Curry K, Bliznyuk N, Rajderkar D, et al. Comparing head ultrasounds and susceptibility-weighted imaging for the detection of low-grade hemorrhages in preterm infants. J Perinatol. 41:736–742. 2021.

Article24. Nongena P, Ederies A, Azzopardi DV, Edwards AD. Confidence in the prediction of neurodevelopmental outcome by cranial ultrasound and MRI in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 95:F388–390. 2010.

Article25. Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 92:529–534. 1978.

Article26. Parodi A, Morana G, Severino MS, Malova M, Natalizia AR, Sannia A, et al. Low-grade intraventricular hemorrhage: is ultrasound good enough? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 28 Suppl. 1:2261–2264. 2015.

Article27. Parodi A, Govaert P, Horsch S, Bravo MC, Ramenghi LA. Cranial ultrasound findings in preterm germinal matrix haemorrhage, sequelae and outcome. Pediatr Res. 87(Suppl 1):13–24. 2020.

Article28. Rees P, Callan C, Chadda KR, Vaal M, Diviney J, Sabti S, et al. Preterm brain injury and neurodevelopmental outcomes: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 150:e2022057442. 2022.

Article29. Riedesel EL. Neonatal cranial ultrasound: advanced techniques and image interpretation. J Pediatric Neurology. 16:106–124. 2018.

Article30. Takashima S, Mito T, Ando Y. Pathogenesis of periventricular white matter hemorrhages in preterm infants. Brain Dev. 8:25–30. 1986.

Article31. Valdez Sandoval P, Hernández Rosales P, Quiñones Hernández DG, Chavana Naranjo EA, García Navarro V. Intraventricular hemorrhage and posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus in preterm infants: diagnosis, classification, and treatment options. Childs Nerv Syst. 35:917–927. 2019.

Article32. Van’t Hooft J, van der Lee JH, Opmeer BC, Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Leenders AG, Mol BW, et al. Predicting developmental outcomes in premature infants by term equivalent MRI: systematic review and metaanalysis. Syst Rev. 4:71. 2015.

Article33. Volpe JJ. Volpe’s Neurology of the Newborn, ed 6. Philadelphia: Elsevier;2018. p. 637–698.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pharmacological Management of Germinal Matrix-Intraventricular Hemorrhage

- Periventricular-Intraventricular Hemorrhage in the Full-term Infant

- Germinal matrix hemorrhage with intraventricular hemorrhage

- Effect of Indomethacin Therpy on Prevention of Intraventricular Hemorrhage in Very

- Cerebral Hemodynamics in Premature Infants