J Korean Neurosurg Soc.

2022 May;65(3):342-347. 10.3340/jkns.2022.0045.

Head Injury during Childbirth

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurosurgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2529577

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2022.0045

Abstract

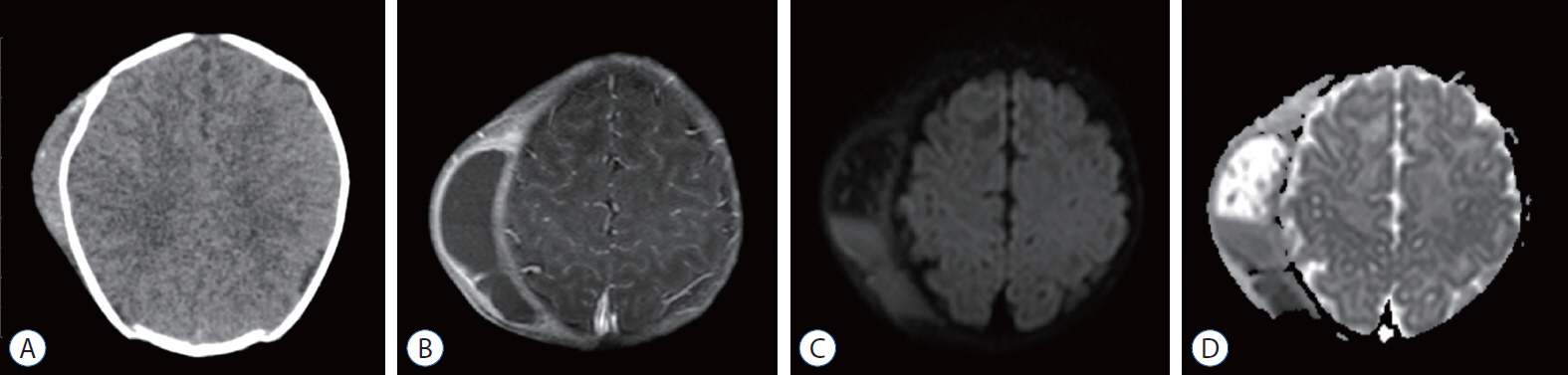

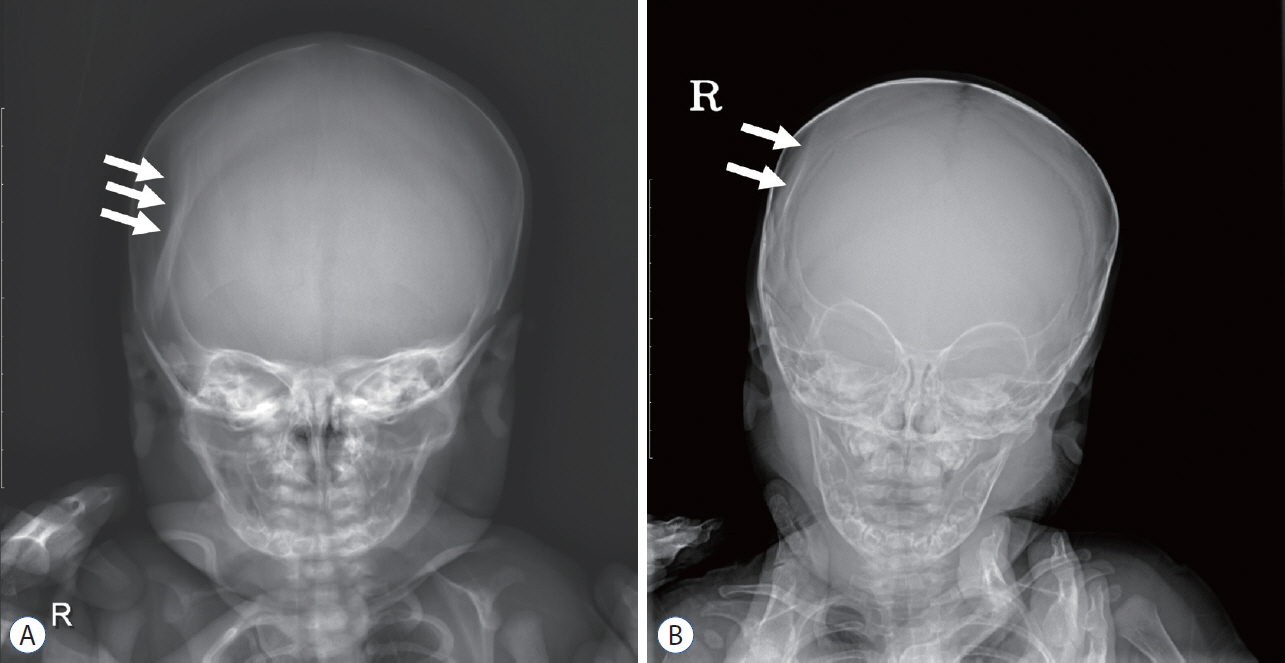

- Head injuries are the most common type of birth injuries. Among them, most of the injuries is limited to the scalp. and the prognosis is good enough to be unnoticed in some cases. Intracranial injuries caused by excessive forces during delivery are rare. However, since some of them can be fatal, it is necessary to suspect it at an early stage and evaluate thoroughly if there are abnormal findings in the patient.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Alexander JM, Leveno KJ, Hauth J, Landon MB, Thom E, Spong CY, et al. Fetal injury associated with cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 90:885–890. 2006.

Article2. Amar AP, Aryan HE, Meltzer HS, Levy ML. Neonatal subgaleal hematoma causing brain compression: report of two cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 4:1470–1474. 2003.

Article3. Ami O, Maran JC, Gabor P, Whitacre EB, Musset D, Dubray C, et al. Three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of fetal head molding and brain shape changes during the second stage of labor. PLoS One. e0215721. 14:2003.

Article4. Blanc F, Bigorre M, Lamouroux A, Captier G. Early needle aspiration of large infant cephalohematoma: a safe procedure to avoid esthetic complications. Eur J Pediatr. 179:265–269. 2020.

Article5. Boulet SL, Alexander GR, Salihu HM, Pass M. Macrosomic births in the united states: determinants, outcomes, and proposed grades of risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 188:1372–1378. 2003.

Article6. Chadwick LM, Pemberton PJ, Kurinczuk JJ. Neonatal subgaleal haematoma: associated risk factors, complications and outcome. J Paediatr Child Health. 32:228–232. 1996.

Article7. Chang HY, Chiu NC, Huang FY, Kao HA, Hsu CH, Hung HY. Infected cephalohematoma of newborns: experience in a medical center in Taiwan. Pediatr Int. 47:274–277. 2005.

Article8. Chung HY, Chung JY, Lee DG, Yang JD, Baik BS, Hwang SG, et al. Surgical treatment of ossified cephalhematoma. J Craniofac Surg. 15:774–779. 2004.

Article9. Cieplinski JAM, Bhutani VK. Lactational and neonatal morbidities associated with operative vaginal deliveries. 1191. Pediatric Research. 39:201. 1996.

Article10. Davis DJ. Neonatal subgaleal hemorrhage: diagnosis and management. CMAJ. 164:1452–1453. 2001.11. Demissie K, Rhoads GG, Smulian JC, Balasubramanian BA, Gandhi K, Joseph KS, et al. Operative vaginal delivery and neonatal and infant adverse outcomes: population based retrospective analysis. BMJ. 329:24–29. 2004.

Article12. Dupuis O, Silveira R, Dupont C, Mottolese C, Kahn P, Dittmar A, et al. Comparison of “instrument-associated” and “spontaneous” obstetric depressed skull fractures in a cohort of 68 neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 192:165–170. 2005.

Article13. Eseonu CI, Sacino AN, Ahn ES. Early surgical intervention for a large newborn cephalohematoma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 51:210–213. 2016.

Article14. Firlik KS, Adelson PD. Large chronic cephalohematoma without calcification. Pediatr Neurosurg. 30:39–42. 1999.

Article15. Gupta R, Cabacungan ET. Neonatal birth trauma: analysis of yearly trends, tisk factors, and outcomes. J Pediatr. 238:174–180. 2021.16. Hanigan WC, Powell FC, Miller TC, Wright RM. Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage in full-term infants. Childs Nerv Syst. 11:698–707. 1995.

Article17. Högberg U, Fellman V, Thiblin I, Karlsson R, Wester K. Difficult birth is the main contributor to birth-related fracture and accidents to other neonatal fractures. Acta Paediatr. 109:2040–2048. 2020.

Article18. Kendall N, Woloshin H. Cephalhematoma associated with fracture of the skull. J Pediatr. 41:125–132. 1952.19. LeBlanc CM, Allen UD, Ventureyra E. Cephalhematomas revisited. when should a diagnostic tap be performed? Clin Pediatr (Phila). 34:86–89. 1995.

Article20. Lee SJ, Kim JK, Kim SJ. The clinical characteristics and prognosis of subgaleal hemorrhage in newborn. Korean J Pediatr. 61:387–391. 2018.

Article21. Levine MG, Holroyde J, Woods JR Jr, Siddiqi TA, Scott M, Miodovnik M. Birth trauma: incidence and predisposing factors. Obstet Gynecol. 63:792–795. 1984.22. Mangurten H, Puppala B. Birth injuries. Fanaroff and Martin’s Neonatal Perinatal Medicine-Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn. ed 8. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier;2006. p. 529–559.23. Martin A, Paddock M, Johns CS, Smith J, Raghavan A, Connolly DJA, et al. Avoiding skull radiographs in infants with suspected inflicted injury who also undergo head CT: “a no-brainer?”. Eur Radiol. 30:1480–1487. 2020.

Article24. Merhar SL, Kline-Fath BM, Nathan AT, Melton KR, Bierbrauer KS. Identification and management of neonatal skull fractures. J Perinatol. 36:640–642. 2016.

Article25. Nachtergaele P, Van Calenbergh F, Lagae L. Craniocerebral birth injuries in term newborn infants: a retrospective series. Childs Nerv Syst. 33:1927–1935. 2017.

Article26. Nakahara K, Shimizu S, Kitahara T, Oka H, Utsuki S, Soma K, et al. Linear fractures invisible on routine axial computed tomography: a pitfall at radiological screening for minor head injury. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 51:272–274. 2011.

Article27. Orman G, Wagner MW, Seeburg D, Zamora CA, Oshmyansky A, Tekes A, et al. Pediatric skull fracture diagnosis: should 3D CT reconstructions be added as routine imaging? J Neurosurg Pediatr. 16:426–431. 2015.

Article28. Plauché WC. Subgaleal hematoma. a complication of instrumental delivery. JAMA. 244:1597–1598. 1980.

Article29. Quayle KS, Jaffe DM, Kuppermann N, Kaufman BA, Lee BC, Park TS, et al. Diagnostic testing for acute head injury in children: when are head computed tomography and skull radiographs indicated? Pediatrics. 99:E11. 1997.

Article30. Reichard R. Birth injury of the cranium and central nervous system. Brain Pathol. 18:565–570. 2008.

Article31. Robinson S. Neonatal posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus from prematurity: pathophysiology and current treatment concepts. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 9:242–258. 2012.

Article32. Towner D, Castro MA, Eby-Wilkens E, Gilbert WM. Effect of mode of delivery in nulliparous women on neonatal intracranial injury. N Engl J Med. 341:1709–1714. 1999.

Article33. Ulma RM, Sacks G, Rodoni BM, Duncan A, Buchman AT, Buchman BC, et al. Management of calcified cephalohematoma of infancy: the University of Michigan 25-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 148:409–417. 2021.

Article34. Wong CH, Foo CL, Seow WT. Calcified cephalohematoma: classification, indications for surgery and techniques. J Craniofac Surg. 17:970–979. 2006.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Childbirth Experience of Participants in Lamaze Childbirth Education

- Do childbirth confidence, prenatal depression, childbirth knowledge, and spousal support influence childbirth fear in pregnant women?

- Factors Influencing Perineal Injury in Women Giving Birth in Natural Childbirth Hospitals

- Effects of a One Session Spouse-Support Enhancement Childbirth Education on Childbirth Self-Efficacy and Perception of Childbirth Experience in Women and their Husbands

- Childbirth outcomes and perineal damage in women with natural childbirth in Korea: a retrospective chart review