Korean J Neurotrauma.

2014 Oct;10(2):123-125. 10.13004/kjnt.2014.10.2.123.

Bi-Coronal Separated Skull Fracture: A Unique and Fatal Type of Traumatic Head Injury in Infancy: A Case Report

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurosurgery, Kyungpook National University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea. shwang@knu.ac.kr

- KMID: 2256245

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.13004/kjnt.2014.10.2.123

Abstract

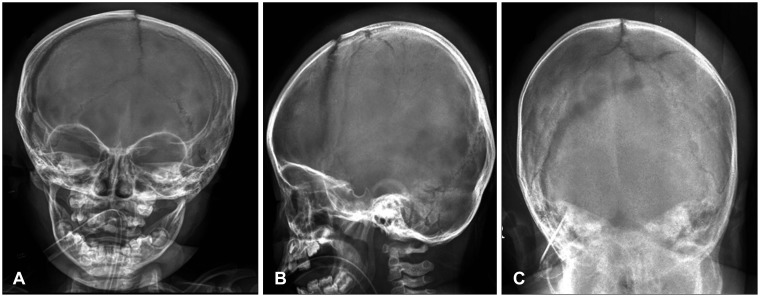

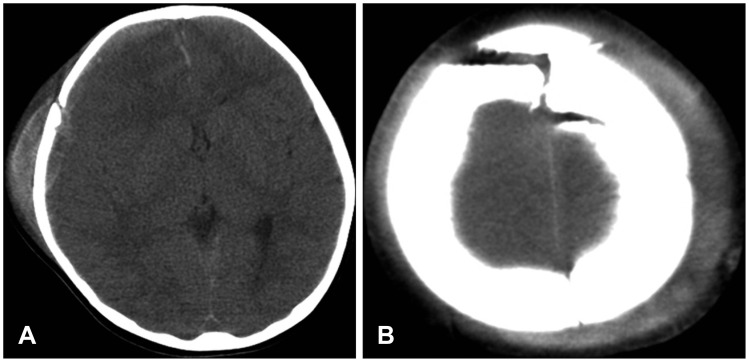

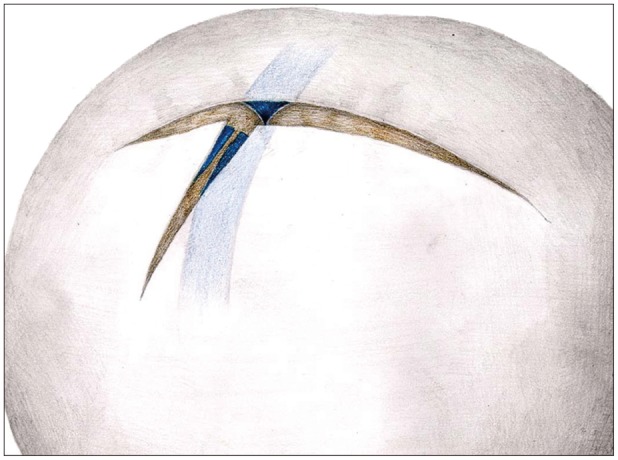

- The infantile skull is malleable, and its sutures are tightly adhering to the underlying dura and venous sinus. These characteristics, in association with the small amount of total blood volume, can result in a specific fatal type of skull fracture, which is unique to infancy. The authors report a case of this injury, and stress the need to pay attention to the possibility of massive bleeding during operation in infants. A 23-month-old female baby presented with semicomatose mentality after sustaining injuries by falling from a second-floor. Plain skull films showed bi-frontal skull fracture crossing the midline. Computed tomography revealed an acute subdural hematoma along the right convexity with severe brain edema. In the emergency operation, the scalp incision exposed massive bleeding from the fracture site. The bleeding was identified as arising from the lacerated and widely separated sagittal sinus beneath the fracture. The patient entered hypovolemic shock immediately after the scalp incision, and died from severe brain edema two days after the trauma and surgery. This case implies that special care should be paid during the operation of patients that have skull fracture overlying the venous sinus, especially when the fracture line is separated.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Gruskin KD, Schutzman SA. Head trauma in children younger than 2 years: are there predictors for complications? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999; 153:15–20. PMID: 9894994.2. Herrera EJ, Viano JC, Aznar IL, Suarez JC. Postraumatic intracranial hematomas in infancy. a 16-year experience. Childs Nerv Syst. 2000; 16:585–589. PMID: 11048633.3. Kodikara S, Pollanen M. Fatal pediatric head injury due to toppled television: does the injury pattern overlap with abusive head trauma? Leg Med (Tokyo). 2012; 14:197–200. PMID: 22498234.

Article4. Kraus JF, Fife D, Conroy C. Pediatric brain injuries: the nature, clinical course, and early outcomes in a defined United States' population. Pediatrics. 1987; 79:501–507. PMID: 3822667.

Article5. Mann KS, Chan KH, Yue CP. Skull fractures in children: their assessment in relation to developmental skull changes and acute intracranial hematomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 1986; 2:258–261. PMID: 3791285.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Acute Growing Skull Fracture: Case Report

- A Case of Traumatic Bilateral Abducens Nerve Palsy Associated with Skull Base Fracture

- Evaluation of Three-Dimentional Computerized Tomography Image of the Growing Skull Fracture on the Orbital Roof

- Delayed Onset Pneumo-hydrocephalus Caused by Traumatic Skull Base Fracture: A case report

- Intrauterine Depressed Skull Fracture of the Newborn associated with Skull Capillary Hemangioma