Korean Circ J.

2009 Jun;39(6):236-242. 10.4070/kcj.2009.39.6.236.

Left Ventricular Dyssynchrony After Acute Myocardial Infarction is a Powerful Indicator of Left Ventricular Remodeling

- Affiliations

-

- 1The Heart Center of Chonnam National University Hospital, Cardiovascular Research Institute of Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea. myungho@chollian.net

- KMID: 1490699

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2009.39.6.236

Abstract

-

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: Left ventricular (LV) remodeling (LVR) after an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has important clinical implications. We have investigated the prognostic relevance of ventricular systolic dyssnchrony as an indicator of LVR after an AMI.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

We enrolled 92 patients (males, 72.8%; mean age, 61.0+/-13.0 years) with an AMI who underwent successful percutaneous coronary intervention. We analyzed the baseline characteristics, the laboratory and echocardiographic findings, and we performed follow-up echocardiography 6 months after the AMI. The patients were divided into two groups: 1) the presence of LVR, which was defined as an increment of LV end systolic volume (LVESV) >20% compared with the baseline examination; and 2) the absence of LVR.

RESULTS

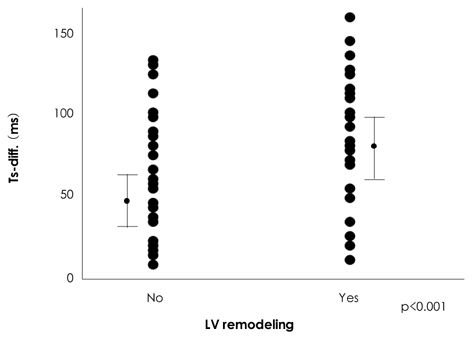

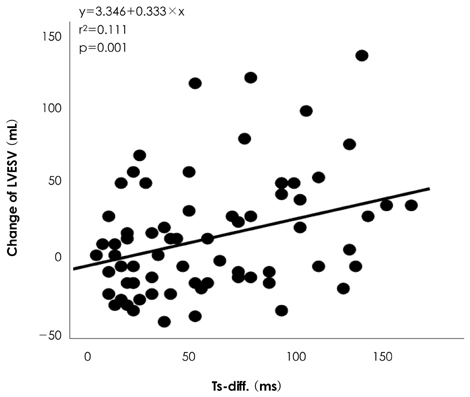

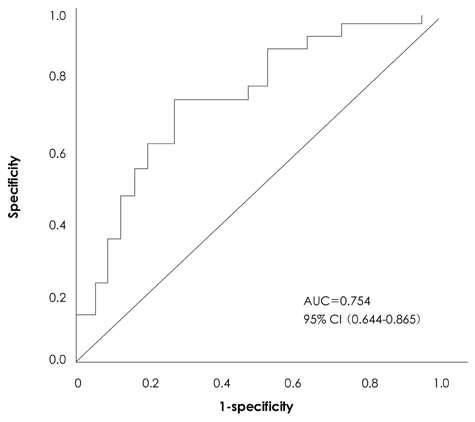

Twenty-seven patients (29.3%) developed LVR after a 6 month follow-up. There was no statistically significant difference in the clinical and angiographic findings between the two groups. With respect to the laboratory findings, the LVR group had a higher peak creatine kinase MB (CK-MB) (149.9+/-155.0 vs. 74.6+/-69.7 U/L, p=0.001) and troponin-I (70.2+/-73.3 vs. 43.2+/-39.5 ng/mL, p=0.024) level than the group without LVR. With respect to echocardiographic findings, the baseline LV ejection fraction (EF) and LVESV were not significantly different (LVESV, 73.0+/-37.3 vs. 91.3+/-52.0 mL, p=0.013; and EF, 58.3+/-13.3 vs. 55.6+/-11.8%, p=0.329) between the groups with and without LVR, respectively. The degree of LV dyssynchrony, which was assessed by tissue Doppler imaging, was significantly higher in the LVR group than the group without LVR (75.2+/-43.4 vs. 38.3+/-32.5 ms), and the degree of LV dyssynchrony was an independent predictor for LVR based on multivariate analysis {hazard ratio (HR)=0.097, p<0.001}. In receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis, the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.754 and a cutoff value of 45.9 predicted the development of LVR with 74.1% sensitivity and 72.3% specificity.

CONCLUSION

The presence of LV dyssynchroncy immediately after a myocardial infarction is an important predictive factor for development LVR.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Long-term Prognosis of Left Ventricular Lead

Seung-Jung Park, Il-Young Oh, Chang-Hwan Yoon, Hyo-Eun Park, Eue-Keun Choi, Gi-Byoung Nam, Kee-June Choi, You-Ho Kim, Yun-Shik Choi, Seil Oh

J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25(10):1462-1466. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.10.1462.

Reference

-

1. Abdelhadi R, Adelstein E, Voigt A, Gorcsan J, Saba S. Measures of left ventricular dyssynchrony and the correlation to clinical and echocardiographic response after cardiac resynchronization therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2008. 102:598–601.2. Cleland J, Freemantle N, Ghio S, et al. Predicting the long-term effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on mortality from baseline variables and the early response a report from the CARE-HF (Cardiac Resynchronization in Heart Failure) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008. 52:438–445.3. Cleland J, Freemantle N, Ghio S, et al. Predicting the long-term effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on mortality from baseline variables and the early response a report from the CARE-HF (Cardiac Resynchronization in Heart Failure) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008. 52:438–445.4. Nicolosi GL. Echocardiography to understand remodeling and to assess prognosis after acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 1998. 65:Suppl 1. S75–S78.5. Bolognese L, Neskovic AN, Parodi G, et al. Left ventricular remodeling after primary coronary angioplasty: patterns of left ventricular dilation and long-term prognostic implications. Circulation. 2002. 106:2351–2357.6. White HD, Norris RM, Brown MA, Brandt PW, Whitlock RM, Wild CJ. Left ventricular end-systolic volume as the major determinant of survival after recovery from myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1987. 76:44–51.7. Udelson JE, Konstam MA. Relation between left ventricular remodeling and clinical outcomes in heart failure patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Card Fail. 2002. 8:Suppl. S465–S471.8. Zhang Y, Chan AK, Yu CM, et al. Left ventricular systolic asynchrony after acute myocardial infarction in patients with narrow QRS complexes. Am Heart J. 2005. 149:497–503.9. Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. 2007 Focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the Canadian Cardiovascular Society endorsed by the American Academy of Family Physicians: 2007 Writing Group to review new evidence and update the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction, writing on behalf of the 2004 writing committee. Circulation. 2008. 117:296–329.10. Bleeker GB, Bax JJ, Schalij MJ, van der Wall EE. Tissue Doppler imaging to assess left ventricular dyssynchrony and resynchronization therapy. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2005. 6:382–384.11. Kang SJ, Song JK, Song JM, et al. Usefulness of Doppler myocardial imaging for the quantitative assessment of ventricular asynchrony in patients with heart failure. Korean Circ J. 2004. 34:492–499.12. Verma A, Meris A, Skali H, et al. Prognostic implications of left ventricular mass and geometry following myocardial infarction. The VALIANT (VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarcTion) echocardiographic study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008. 1:582–591.13. Parodi G, Memisha G, et al. Prevalence, predictors, time course, and long-term clinical implications of left ventricular functional recovery after mechanical reperfusion for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2007. 100:1718–1722.14. White HD, Norris RM, Brown MA, Brandt PW, Whitlock RM, Wild CJ. Left ventricular end-systolic volume as the major determinant of survival after recovery from myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1987. 76:44–51.15. Yu CM, Fung JW, Chan CK, et al. Comparison of efficacy of reverse remodeling and clinical improvement for relatively narrow and wide QRS complexes after cardiac resynchronization therapy for heart failure. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004. 15:1058–1065.16. Giannuzzi P, Temporelli PL, Nicolosi GL, et al. Doppler-derived mitral deceleration time as a strong prognostic marker of left ventricular remodeling and survival after acute myocardial infarction: results of the GISSI-3 echo substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004. 43:1646–1653.17. Giannuzzi P, Temporelli PL, Bosimini E, et al. Heterogeneity of left ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction: results of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza-nell'Infarto Miocardico-3 Echo Substudy. Am Heart J. 2001. 141:131–138.18. Savoye C, Equine O, Tricot O, et al. Left ventricular remodeling after anterior wall acute myocardial infarction in modern clinical practice (from the REmodelage VEntriculaire [REVE] Study Group). Am J Cardiol. 2006. 98:1144–1149.19. Sato A, Aonuma K, Imanaka-Yoshida K, et al. Serum tenascin-C might be a novel predictor of left ventricular remodeling and prognosis after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006. 47:2319–2325.20. Nagashima M, Itoh A, Otsuka M, Kasanuki H, Haze K. Reperfusion phenomenon is a strong predictor of left ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction. Circ J. 2005. 69:884–889.21. Choi SY, Tahk SJ, Yoon MH, et al. Comparison of TIMI myocardial perfusion grade with coronary flow reserve for prediction of recovery of LV function and LV remodeling in acute myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J. 2004. 34:247–257.22. McKay RG, Pfeffer MA, Pasternak RC, et al. Left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction: a corollary to infarct expansion. Circulation. 1986. 74:693–702.23. Pirolo JS, Hutchins GM, Moore GW. Infarct expansion: pathologic analysis of 204 patients with a single myocardial infarct. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986. 7:349–354.24. Popovic AD, Neskovic AN, Marinkovic J, Thomas JD. Acute and long-term effects of thrombolysis after anterior wall acute myocardial infarction with serial assessment of infarct expansion and late ventricular remodeling. Am J Cardiol. 1996. 77:446–450.25. Mollema SA, Bleeker GB, Liem SS, et al. Does left ventricular dyssynchrony immediately after acute myocardial infarction result in left ventricular dilatation? Heart Rhythm. 2007. 4:1144–1148.26. Carluccio E, Biagioli P, Alunni G, et al. Patients with hibernating myocardium show altered left ventricular volumes and shape, which revert after revascularization: evidence that dyssynergy might directly induce cardiac remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006. 47:969–977.27. Yu CM, Sanderson JE, Marwick TH, Oh JK. Tissue Doppler imaging a new prognosticator for cardiovascular diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007. 49:1903–1914.28. Yao M, Dieterle T, Hale SL, et al. Long-term outcome of fetal cell transplantation on postinfarction ventricular remodeling and function. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003. 35:661–670.29. Kang HJ, Kim HS, Na SH, et al. Six months follow up results of "granulocytes-colony stimulating factor" based stem cell therapy in patients with myocardial infarction: MAGIC cell randomized controlled trial. Korean Circ J. 2006. 36:99–107.30. Chang SA, Kim HK, Lee HY, et al. Restoration of left ventricular synchronous contraction after acute myocardial infarction by stem cell therapy: new insights into the therapeutic implication of stem cell therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2008. 94:995–1001.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Left Ventricular Diastolic Dyssynchrony in Post-Myocardial Infarction Patients: Does It Predict Future Left Ventricular Remodeling?

- Ventricular Remodeling after Acute Myocardial Infarction

- Two-Dimensional Echocardiographic Predictors of Ventricular Enlargement after Acute Myocardial Infarction

- Acute Myocardial Infarction in 14-Year-Old Male of Primary Pulmonary Hypertension with Left Ventricular Hypertrophy : A Case Report

- Incidence of Left Ventricular Thrombus after Acute Myocardial Infarction