Changes in the Cesarean Section Rate in Korea (1982-2012) and a Review of the Associated Factors

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Kyung Hee University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. baecw@khnmc.or.kr

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kyung Hee University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2129623

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2014.29.10.1341

Abstract

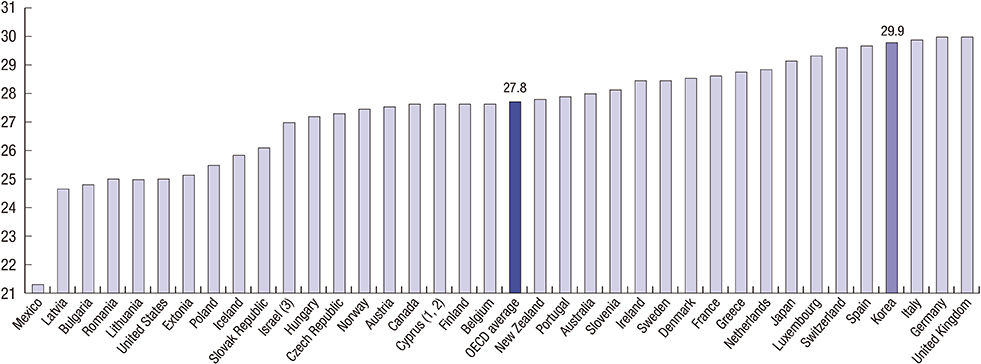

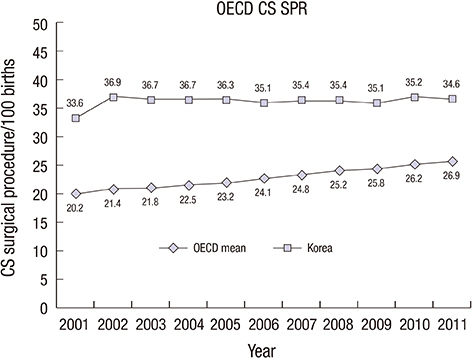

- Although Cesarean section (CS) itself has contributed to the reduction in maternal and perinatal mortality, an undue rise in the CS rate (CSR) has been issued in Korea as well as globally. The CSR in Korea increased over the past two decades, but has remained at approximately 36% since 2006. Contributing factors associated with the CSR in Korea were an improvement in socio-economic status, a higher maternal age, a rise in multiple pregnancies, and maternal obesity. We found that countries with a no-fault compensation system maintained a lower CSR compared to that in countries with civil action, indicating the close relationship between the CSR and the medico-legal system within a country. The Korean government has implemented strategies including an incentive system relating to the CSR or encouraging vaginal birth after Cesarean to decrease CSR, but such strategies have proved ineffective. To optimize the CSR in Korea, efforts on lowering the maternal childbearing age or reducing maternal obesity are needed at individual level. And from a national view point, reforming health care system, which could encourage the experienced obstetricians to be trained properly and be relieved from legal pressure with deliveries is necessary.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 8 articles

-

Secular trends in cesarean sections and risk factors in South Korea (2006–2015)

Ho Yeon Kim, Dokyum Lee, Jinsil Kim, Eunjin Noh, Ki-Hoon Ahn, Soon-Cheol Hong, Hai-Joong Kim, Min-Jeong Oh, Geum Joon Cho

Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2020;63(4):440-447. doi: 10.5468/ogs.19212.Summary of clinically diagnosed amniotic fluid embolism cases in Korea and disagreement with 4 criteria proposed for research purpose

Jin-ha Kim, Hyun-Joo Seol, Won Joon Seong, Hyun-Mee Ryu, Jin-Gon Bae, Joon Seok Hong, Jeong Yang, Ji-Hee Sung, Suk-Joo Choi, Soo-young Oh, Cheong-Rae Roh

Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2021;64(2):190-200. doi: 10.5468/ogs.20195.Effects of Pregnancy and Delivery Methods on Change in Ankylosing Spondylitis Treatment Using the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service Claims Database

Jung Sun Lee, Ji Seon Oh, Ye-Jee Kim, Seokchan Hong, Chang-Keun Lee, Bin Yoo, Yong-Gil Kim

J Korean Med Sci. 2019;34(37):. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e238.Pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium outcomes in female firefighters in Korea

Juha Park, Yeon-Soon Ahn, Min-Gi Kim

Ann Occup Environ Med. 2020;32(1):. doi: 10.35371/aoem.2020.32.e8.The collapse of infrastructure for childbirth: causes and consequences

Soo-young Oh

J Korean Med Assoc. 2016;59(6):417-423. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2016.59.6.417.Risk of Emergency Operations, Adverse Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes according to the Planned Gestational Age for Cesarean Delivery

Seung Mi Lee, Joong Shin Park, Young Mi Jung, Su Ah Kim, Ji Hyun Ahn, Jina Youm, Chan-Wook Park, Jong Kwan Jun

J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(7):. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e51.Risk of Pregnancy Complications and Low Birth Weight Offsprings in Korean Women With Rheumatic Diseases: A Nationwide Population-Based Study

Jin-Su Park, Min Kyung Chung, Hyunsun Lim, Jisoo Lee, Chan Hee Lee

J Korean Med Sci. 2021;37(2):e18. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e18.How Can We Adopt the Glucose Tolerance Test to Facilitate Predicting Pregnancy Outcome in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus?

Kyeong Jin Kim, Nam Hoon Kim, Jimi Choi, Sin Gon Kim, Kyung Ju Lee

Endocrinol Metab. 2021;36(5):988-996. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2021.1107.

Reference

-

1. Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet. 1985; 2:436–437.2. Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, Zavaleta N, Carroli G, Velazco A, Shah A, Campodónico L, Bataglia V, Faundes A, et al. Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet. 2006; 367:1819–1829.3. Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Gülmezoglu AM, Souza JP, Taneepanichskul S, Ruyan P, Attygalle DE, Shrestha N, Mori R, Nguyen DH, et al. Method of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in Asia: the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health 2007-08. Lancet. 2010; 375:490–499.4. Williams JW. Cesarean delivery and peripartum hysterectomy. In : Cunningham FG, Williams JW, editors. Williams Obstetrics. 23th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical;2010. p. 544–549.5. Jang WM, Eun SJ, Lee CE, Kim Y. Effect of repeated public releases on cesarean section rates. J Prev Med Public Health. 2011; 44:2–8.6. Korea National Health Insurance Service. Cesarean delivery survey in Korea, 2000. Seoul: Korea National Health Insurance Service;2001. p. 1–8.7. Kim SK, Cho AJ, Kim YK, Park SK, Lee KW. Survey on the National Fertility, Family Health and Welfare. Seoul: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2004. p. 299–305.8. Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Cesarean delivery evaluation report in Korea, 2013. Seoul: Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service;2013. p. 2–5.9. Statistics Korea. 2012 Social indicators in Korea. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2013.10. Korean Statistical Information Service. Vital statistics for Provinces (Number and Rate). accessed on 21 June 2014. Available at http://kosis.kr/statisticsList/statisticsList_01List.jsp?vwcd=MT_ZTITLE&parentId=A.11. OECD iLibrary. OECD Health data. accessed on 21 June 2014. Available at http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/statistics.12. OECD. OECD Family database. accessed on 21 June 2014. Available at http://www.oecd.org/social/family/database.13. Office for National Statistics. Births in England and Wales, 2012. accessed on 21 June 2014. Available at http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/birth-summary-tables--england-and-wales/2012/stb-births-in-england-and-wales-2012.html.14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National vital statistics reports: births. accessed on 21 June 2014. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/nvsr.htm.15. Health & Social Care Information Centre. NHS maternity statistics - England, 2012-13. accessed on 21 June 2014. Available at http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB12744.16. Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Cesarean section delivery in Japan. accessed on 21 June 2014. Available at http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/iryosd/11/.17. Kim HY. A study for the improving plans of the system of Korean medical dispute solution: centered on procedure and procurement procedure of financial resources. Seoul: Yonsei University;2008.18. Gibbons L, Belizán JM, Lauer JA, Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Althabe F. The global numbers and costs of additionally needed and unnecessary caesarean sections performed per year: overuse as a barrier to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization;2010. p. 31.19. What is the right number of caesarean sections? Lancet. 1997; 349:815.20. Peskin EG, Reine GM. A guest editorial: what is the correct cesarean rate and how do we get there? Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002; 57:189–190.21. Sachs BP, Kobelin C, Castro MA, Frigoletto F. The risks of lowering the cesarean-delivery rate. N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:54–57.22. Greene MF. Two hundred yr of progress in the practice of midwifery. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367:1732–1740.23. Im JK, Park CM. Perinatal mortality patterns in Korea. Health Soc Welf Rev. 1982; 2:67–78.24. Chung SH, Choi YS, Bae CW. Changes in the neonatal and infant mortality rate and the causes of death in Korea. Korean J Pediatr. 2011; 54:443–455.25. Chang JY, Lee KS, Hahn WH, Chung SH, Choi YS, Shim KS, Bae CW. Decreasing trends of neonatal and infant mortality rates in Korea: compared with Japan, USA, and OECD nations. J Korean Med Sci. 2011; 26:1115–1123.26. Han DH, Lee KS, Chung SH, Choi YS, Hahn WH, Chang JY, Bae CW. Decreasing pattern in perinatal mortality rates in Korea: in comparison with OECD nations. Korean J Perinatol. 2011; 22:209–220.27. Chung SH, Choi YS, Bae CW. Changes in neonatal epidemiology during the last 3 decades in Korea. Neonatal Med. 2013; 20:249–257.28. Cho JH, Choi SK, Chung SH, Choi YS, Bae CW. Changes in neonatal and perinatal vital statistics during last 5 decades in Republic of Korea: compared with OECD nations. Neonatal Med. 2013; 20:402–412.29. Statistics Korea. Population and housing census, 1985. accessed on 21 June 2014. Available at http://kosis.kr/wnsearch/totalSearch.jsp.30. Statistics Korea. Population and housing census, 1985. accessed on 21 June 2014. Available at http://kosis.kr/wnsearch/totalSearch.jsp.31. Lee SI, Khang YH, Yun S, Jo MW. Rising rates, changing relationships: caesarean section and its correlates in South Korea, 1988-2000. BJOG. 2005; 112:810–819.32. Feng XL, Xu L, Guo Y, Ronsmans C. Factors influencing rising caesarean section rates in China between 1988 and 2008. Bull World Health Organ. 2012; 90:30–39. 39A33. Bayrampour H, Heaman M. Advanced maternal age and the risk of cesarean birth: a systematic review. Birth. 2010; 37:219–226.34. Chan BC, Lao TT. Effect of parity and advanced maternal age on obstetric outcome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008; 102:237–241.35. O'Leary CM, de Klerk N, Keogh J, Pennell C, de Groot J, York L, Mulroy S, Stanley FJ. Trends in mode of delivery during 1984-2003: can they be explained by pregnancy and delivery complications? BJOG. 2007; 114:855–864.36. Moore EK, Irvine LM. The impact of maternal age over forty yr on the caesarean section rate: six year experience at a busy district general hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014; 34:238–240.37. Lim S, Shin H, Song JH, Kwak SH, Kang SM, Won Yoon J, Choi SH, Cho SI, Park KS, Lee HK, et al. Increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Korea: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey for 1998-2007. Diabetes Care. 2011; 34:1323–1328.38. Ha JY, Kim HJ, Kang CS, Park SC. An association of gestational weight gain and prepregnancy body mass index with perinatal outcomes. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 54:575–581.39. MacDorman M, Declercq E, Menacker F. Recent trends and patterns in cesarean and vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) deliveries in the United States. Clin Perinatol. 2011; 38:179–192.40. Simon AE, Uddin SG. National trends in primary cesarean delivery, labor attempts, and labor success, 1990-2010. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 209:554.e1–554.e8.41. Washington S, Caughey AB, Cheng YW, Bryant AS. Racial and ethnic differences in indication for primary cesarean delivery at term: experience at one U.S. Institution. Birth. 2012; 39:128–134.42. Barber EL, Lundsberg LS, Belanger K, Pettker CM, Funai EF, Illuzzi JL. Indications contributing to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 118:29–38.43. Thomas J, Paranjothy S. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit. National sentinel caesarean section audit report. London: RCOG Press;2001. p. 120.44. Kim HK. Impact factors of Korean women's cesarean section according to ecological approach. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2011; 17:109–117.45. Habiba M, Kaminski M, Da Frè M, Marsal K, Bleker O, Librero J, Grandjean H, Gratia P, Guaschino S, Heyl W, et al. Caesarean section on request: a comparison of obstetricians' attitudes in eight European countries. BJOG. 2006; 113:647–656.46. Kim YM, Go SK. Factors determining cesarean section frequency rates of the OBGY clinics in metropolitan area. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2002; 8:389–401.47. Lo JC. Financial incentives do not always work: an example of cesarean sections in Taiwan. Health Policy. 2008; 88:121–129.48. Grant D. Physician financial incentives and cesarean delivery: new conclusions from the healthcare cost and utilization project. J Health Econ. 2009; 28:244–250.49. Keeler EB, Fok T. Equalizing physician fees had little effect on cesarean rates. Med Care Res Rev. 1996; 53:465–471.50. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion No. 17. Guidelines for vaginal delivery after cesarean birth. Washington DC: American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists;1984.51. Menacker F, Declercq E, Macdorman MF. Cesarean delivery: background, trends, and epidemiology. Semin Perinatol. 2006; 30:235–241.52. McMahon MJ, Luther ER, Bowes WA Jr, Olshan AF. Comparison of a trial of labor with an elective second cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:689–695.53. Smith GC, Pell JP, Cameron AD, Dobbie R. Risk of perinatal death associated with labor after previous cesarean delivery in uncomplicated term pregnancies. JAMA. 2002; 287:2684–2690.54. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice bulletin no. 115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116:450–463.55. Park JS. Is VBAC(vaginal birth after cesarean) really safe? J Korean Med Assoc. 2005; 48:489–500.56. Clark SL, Scott JR, Porter TF, Schlappy DA, McClellan V, Burton DA. Is vaginal birth after cesarean less expensive than repeat cesarean delivery? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 182:599–602.57. Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, Meyers JA. Reducing obstetric litigation through alterations in practice patterns. Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 112:1279–1283.58. Dodd JM, Crowther CA, Huertas E, Guise JM, Horey D. Planned elective repeat caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for women with a previous caesarean birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 12:CD004224.59. Marroquin GA, Tudorica N, Salafia CM, Hecht R, Mikhail M. Induction of labor at 41 weeks of pregnancy among primiparas with an unfavorable Bishop score. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013; 288:989–993.60. Heffner LJ, Elkin E, Fretts RC. Impact of labor induction, gestational age, and maternal age on cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 102:287–293.61. Luthy DA, Malmgren JA, Zingheim RW. Cesarean delivery after elective induction in nulliparous women: the physician effect. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 191:1511–1515.62. Rayburn WF, Zhang J. Rising rates of labor induction: present concerns and future strategies. Obstet Gynecol. 2002; 100:164–167.63. Vrouenraets FP, Roumen FJ, Dehing CJ, van den Akker ES, Aarts MJ, Scheve EJ. Bishop score and risk of cesarean delivery after induction of labor in nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 105:690–697.64. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins -- Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 107: Induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114:386–397.65. MacLennan AH. A 'no-fault' cerebral palsy pension scheme would benefit all Australians. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011; 51:479–484.66. Branch DW, Silver RM. Managing the primary cesarean delivery rate. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 55:946–960.67. Chen HY, Chauhan SP, Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM, Abuhamad AZ. Electronic fetal heart rate monitoring and its relationship to neonatal and infant mortality in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 204:491.e1–491.e10.68. Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Lauer JA, Bing-Shun W, Thomas J, Van Look P, Wagner M. Rates of caesarean section: analysis of global, regional and national estimates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007; 21:98–113.69. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 559: Cesarean delivery on maternal request. Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 121:904–907.70. Statistics Korea. Statistics of birth and death, 2013 (the interim report). accessed on 21 June 2014. Available at http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/2/2/1/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=311884.71. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (College). Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, Rouse DJ. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 210:179–193.72. Oh SY, Kwon JY, Shin JH, Kim A. The influence of obstetric no-fault compensation act on future career of residents in obstetrics and gynecology. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 55:461–467.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Factors on the Gap between Predicted Cesarean Section Rate and Real Cesarean Section Rate in Tertiary Hospitals

- A Study on the Effect of Physician Characteristics on the Cesarean Section Rate

- Effects of Diagnosis-Related Group-Based Payment System on the Risk-Adjusted Cesarean Section Rate

- Impact Factors of Korean Women's Cesarean Section according to Ecological Approach

- General anesthesia for cesarean section: are we doing it well?